A small group of fishers ply the shallow coastal water along Pooneryn in northern Sri Lanka, an impoverished, remote area within striking distance of India’s southern tip. It is where Gautam Adani — the Indian billionaire who is Asia’s richest person and has vaulted ahead of Jeff Bezos this year — plans to build renewable power plants, thrusting him into the heart of an international political clash.

With Sri Lanka in the throes of its worst economic crisis since its independence from Britain in 1948, India is re-engaging and attempting to tilt the balance in a strategic tussle with China on the island, a pivotal battleground because it lies on key global shipping lanes and plays into New Delhi’s fear of encirclement from its Asian rival.

At the forefront of those efforts is Adani, who is a long-time supporter of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and has been accused by some Sri Lankan lawmakers of signing opaque port and energy deals closely tied to New Delhi’s interests, something his group has always denied, saying the investments meet Sri Lanka’s needs.

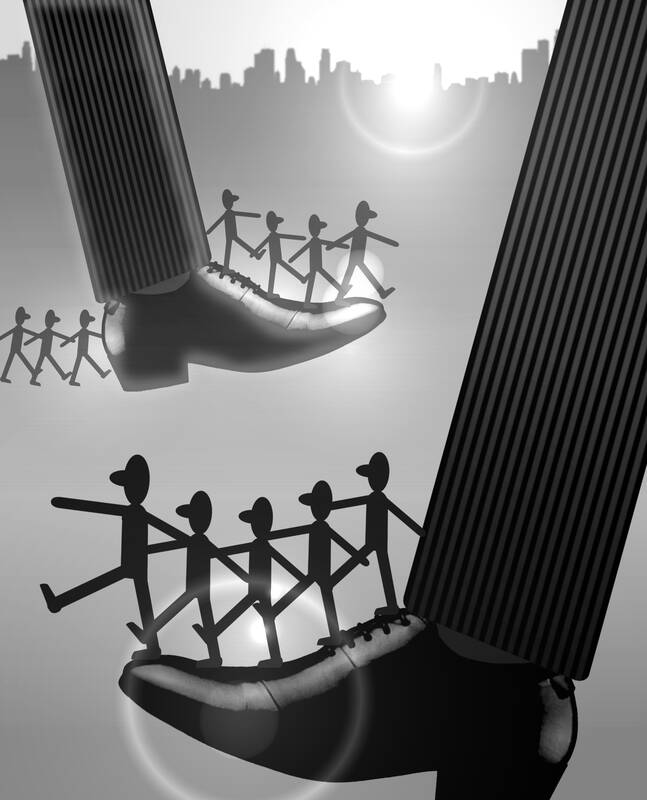

I llustration: Yusha

Sitting atop a US$137 billion wealth pile, Adani controls a sprawling empire that spans ports, coal plants, power generation and distribution. While he derives the vast majority of his fortune from India, Adani has gradually made more overseas deals and told shareholders in July that he seeks a “broader expansion” beyond India’s borders with “several” foreign governments approaching his conglomerate to develop their infrastructure.

Those moves and Adani’s perceived closeness to Modi’s administration have spurred suggestions the tycoon could be the cash cow for India’s pushback against China, whose Belt and Road Initiative is intended to increase Beijing’s influence in strategic countries and on the global stage.

“In countries that the Indian government has better relations than the Chinese government, Adani could find success,” said Akhil Ramesh, a resident fellow at the Pacific Forum research institute in Honolulu.

While India lacks the financial firepower of its neighbor, Adani’s investments in countries such as Israel and Sri Lanka compete with Chinese state-owned firms.

It is in Sri Lanka where that tension is playing out most acutely. Adani’s investments there were described by multiple Indian and Sri Lankan officials as advancing the Modi administration’s objectives on the tear-drop shaped island, in much the same way that his businesses in ports, power and cement coincide with the government’s economic priorities at home.

Adani has repeatedly denied that his firms receive special treatment from Modi’s government.

In October last year, Adani emphasized the “strong bonds” between the two nations when he met with then-Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa, just months after inking a US$750 million Colombo port deal. It was a rare example of Indian infrastructure investment in Sri Lanka, after Colombo in previous years pivoted toward Beijing — which has funded everything from highways to ports through the Belt and Road Initiative — and splurged on debt-fueled projects.

Soon after that meeting, a team from Adani Group — which is targeting a US$70 billion move toward green energy — toured Sri Lanka’s north. The region has been starved of investment since the end of the country’s 26-year civil war in 2009.

The visit seemed a turning point, as not long after the Rajapaksa administration terminated Chinese solar projects on islands in the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka because of security concerns from New Delhi, multiple people with direct knowledge of the matter said.

China’s embassy in Colombo later confirmed the end of the solar projects on social media.

Early this year, Adani quietly signed memorandums of understanding to build 500 megawatts of renewable energy projects in Pooneryn and Mannar, other northern districts close to India, local media reports confirmed months later through a post on Twitter from Sri Lankan Minister of Power and Energy Kanchana Wijesekera.

India “is worried about Chinese access to the Indian Ocean, and being encircled by Chinese friendly regimes in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh,” said Katharine Adeney, a professor and expert on South Asian politics at the University of Nottingham.

Adani’s supplanting of China’s solar power projects represents “a strategic move and one that we are likely to see more of,” she said.

Spokespeople for Adani Group and India’s foreign ministry declined to comment. China’s ambassador in Colombo and a representative for Sri Lanka’s president did not respond to requests for comment. Wijesekera also did not respond to messages.

The Indian billionaire has even started to publicly criticize China, saying in September at a conference in Singapore that China was “increasingly isolated” with its Belt and Road Initiative facing “resistance.”

Even so, Adani’s global ambitions face challenges. As the billionaire boosted his influence in Sri Lanka, local media and opposition politicians have claimed that his companies have skirted due process.

Soon after Sri Lankan media reported that Adani signed the northern power agreements in March, Ajith Perera, the chief executive of Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) — the country’s largest opposition party — protested what he called Adani’s “back door” entry into the country’s energy industry. Perera wrote on Facebook that Rajapaksa’s administration was “pampering” Modi’s “notorious friends.”

“It must be transparent and it must be bidded out,” prominent SJB lawmaker Eran Wickramaratne said in an interview with Bloomberg News, adding that the Sri Lankan parliament has not been allowed to scrutinize the contracts.

“The color of the investment doesn’t matter to us — but investment must be transparent, it must be an equal playing field,” he said, adding that “we can’t fault the foreign investor, we have to fault our own government and our system.”

A spokesperson for Rajapaksa did not respond to a request for comment.

In a statement on the protests to the Press Trust of India news service, the Adani Group said its intent in investing in Sri Lanka “is to address the needs of a valued neighbor. As a responsible corporate, we see this as a necessary part of the partnership that our two nations have always shared.”

In June, the Ceylon Electricity Board Engineers’ Union threatened to strike over legislation that removed public competition from the allocation of wind and solar projects, pointing specifically at Adani’s plans in northern Sri Lanka.

Later that month, the chairman of the state-run utility told a parliamentary committee that Modi’s government had pressured Sri Lanka to accept Adani’s energy proposals. He resigned days later, claiming he was “emotional” when making the statement, and after Rajapaksa “categorically” denied the allegations. A spokesperson for the utility did not respond to a request for comment.

“We are clearly disappointed by the detraction that seems to have come about,” a report by Indian television channel NDTV quoted the Adani Group as saying at the time. “The fact is that the issue has already been addressed by and within the Sri Lankan Government.”

Protests ensued in Colombo. The crowds held signs reading: “Stop Adani” and “Modi Don’t Exploit Our Crisis.”

Adani, like Modi, hails from the Western Indian state of Gujarat. He built his fortune over the past decade partly by focusing on business areas that were central to Modi’s national priorities.

In 2002, months after Modi became chief minister of Gujarat, more than 1,000 people, most of them Muslims, were killed in the state in one of India’s worst periods of sectarian rioting. Modi, a Hindu nationalist was accused by human rights groups of doing little to stop the violence, allegations he has denied and were subsequently dismissed by the Indian Supreme Court.

Adani, whose businesses had yet to expand across the breadth of India, was among local Gujarati businesspeople who helped create a biannual investment summit in the state that gave Modi a platform to promote his pro-business image. Adani’s fortune has grown exponentially since Modi was elected prime minister in 2014.

In the past few years, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has funneled billions of dollars into South Asia, but Sri Lanka’s grinding economic crisis, coupled with food, fuel, medical and power shortages, presented India with a window to push its influence with its smaller, strategic neighbor. New Delhi has sent Sri Lanka US$4 billion of aid and credit lines this year as it also attempts to both stem a humanitarian catastrophe on its doorstep and further its geopolitical objectives.

Rajapaksa fled the country in July, handing the reins to Ranil Wickremesinghe following a bout of violent unrest. Since then, Wickremesignhe has sought to dial back anti-Chinese sentiment as his administration initiates debt restructuring talks with both Beijing and New Delhi.

“Ranil’s very much a pragmatic leader in that he realizes every international actor is needed at this moment, he’s not going to take sides,” said Bhavani Fonseka, a senior researcher and lawyer at the Colombo-based Centre for Policy Alternatives.

At the same time, Adani’s renewable moves “didn’t get the attention it should have” amid Sri Lanka’s wider unrest, and now the relative calm there might be an opportunity for re-examination, she said.

For Modi, securing a foothold in Colombo’s new port is seen as particularly important, with China constructing the adjacent Colombo Port City, a Dubai-like financial hub, and operating the Colombo International Container Terminals.

While India and Adani saw a setback in Sri Lanka when a deal to develop the East Container Terminal at the new port was canned by Rajapaksa after pushback from unions, the billionaire scored a win last year.

New deals were struck and Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone was awarded the right to develop, build and operate the West Container Terminal, holding a 51 percent stake in a joint venture with local conglomerate John Keells Holdings.

In a rare insight into the linkages between Adani and Modi, at a Cabinet meeting in March last year, Sri Lankan ministers said New Delhi had nominated Adani for the project, a claim that later that month an Indian Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson said was “factually incorrect.”

The project was also not publicly tendered. India would have found it difficult to outbid China in an open process, people with direct knowledge of the deal said. This month, China Harbour Engineering was also selected by Sri Lanka’s government to help construct the East Container Terminal.

India likely has a vested interest in having one of its own companies build a port terminal close to China’s own port project, said Samantha Custer, director of policy analysis at AidData, a research unit at William & Mary University in Virginia.

Indian companies are often disadvantaged due to Beijing tying project finance to implementation by state-subsidized Chinese firms, she said.

“One of the motivations for moving forward is geostrategic in order for a politically connected Indian company to be willing to accept delayed or uncertain economic returns,” Custer said. “That said, an uncertain economic return on investment is not the same thing as no return on investment, and the Adani Group likely recognizes that this is a long-term play with a high risk and high reward proposition.”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its