Earlier this summer, the UN convened its Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal. The goal was to “to propel much needed science-based innovative solutions aimed at starting a new chapter of global ocean action.”

The world needs a “sustainably managed ocean,” said UN Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs Miguel de Serpa Soares, who hailed the conference as an “enormous success.” If only.

The ocean’s importance cannot be overstated. It is the planet’s largest biosphere, hosting up to 80 percent of all life on Earth. It generates 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe and absorbs one-quarter of all carbon-dioxide emissions, essential for climate and weather regulation. It is also economically vital, with about 120 million people employed in fisheries and related activities, mostly for small-scale enterprises in developing countries.

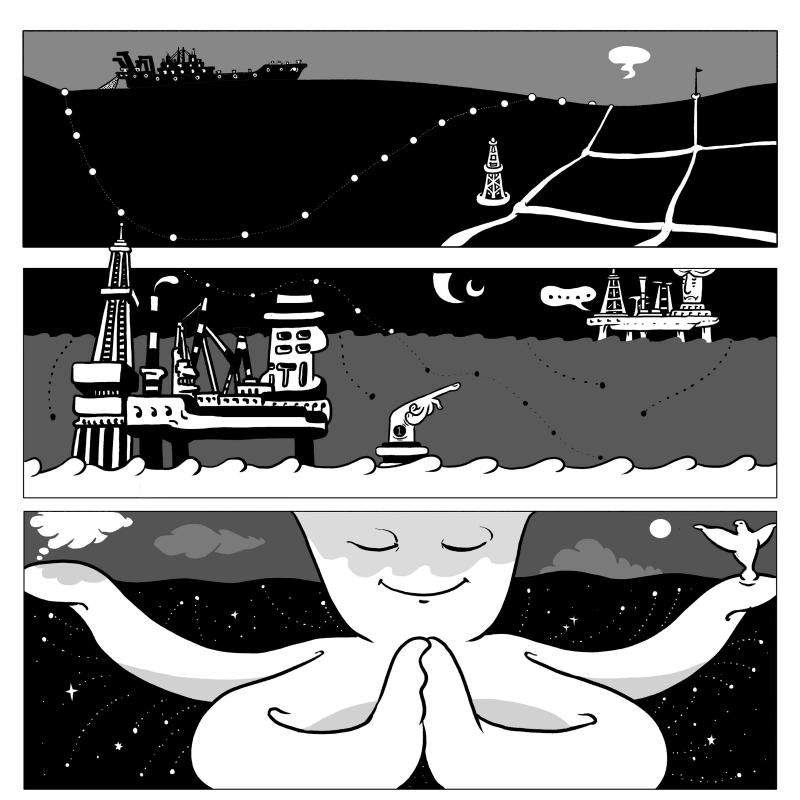

Illustration: Mountain People

Yet over the past four decades, the ocean has come under unprecedented pressure, largely owing to the rapid growth of commercial maritime activity. This growth is particularly significant in exclusive economic zones (EEZ), contiguous areas of territorial water that stretch about 370km from country coastlines.

The principle of national sovereignty over EEZs was enshrined in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982. In the years that followed, governments sold off vast tracts of ocean territory through state licenses and concessions, effectively handing over management of marine ecosystems to the private sector.

Policymakers apparently reasoned that corporations would have a financial interest in adopting responsible business practices to preserve the resources from which they were extracting so much value. Instead, widespread oil and gas exploration, industrial fishing and frenetic maritime trade have, as UN Special Envoy for the Ocean Peter Thomson has put it, caused “the ocean’s health” to “spiral into decline.”

Marine acidification and heating reached record levels last year. Only about 13 percent of the ocean now qualifies as “marine wilderness” (biologically and ecologically intact seascapes that are mostly free of human disturbance). More than one-third of marine mammals and nearly one-third of reef-forming corals are now threatened with extinction.

It was against this backdrop that the UN Ocean Conference was convened to “halt the destruction” of ocean ecosystems. However, despite much lofty rhetoric, all that came of it were vague pronouncements: the UN’s 193 members reaffirmed their pledge to bolster maritime governance by (among other things) strengthening data collection and promoting finance for nature-based solutions.

Beyond Colombia’s recently announced plans to create four new marine-protected areas, no binding commitments were made — and, tellingly, the deadlock on deep-sea mining was not broken. Whereas many advanced economies, including Japan and South Korea, support the controversial practice, Pacific countries such as Palau and Fiji demanded an industrywide moratorium, citing the lack of environmental data.

The key takeaway from the conference was that the UN remains committed to incremental change, with the private sector firmly in control. This is reflected in an emphasis on “natural capital” solutions, which involve putting a price on nature to save it. The neoliberal policymaking that created today’s crisis has undergone an ideological makeover. Where shareholder capitalism failed to ensure self-regulation by private owners, “stakeholder capitalism” supposedly would succeed, as companies would balance the competing interests of investors, workers, communities and the environment.

It is not hard to see why stakeholder capitalism is so appealing: It gives the impression that we can have our cake and eat it. However, when it comes to the ocean, the cake is already past its expiration date. Given current technological constraints, protecting the ocean from further degradation precludes any additional maritime industrialization.

Why does the UN believe that private firms will become responsible stewards of the planet? The rapid degradation of marine ecosystems is not exactly new information, yet corporations have only increased their damaging activities. Realistically, stakeholder capitalism would merely defer difficult decisions about profit maximization in a climate-constrained world to future generations.

Now, the world has an opportunity to embrace a more promising approach to protecting the ocean: the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. The meetings, which resumed this week in New York, are expected to produce a legal framework for governing all marine areas beyond coastal countries’ EEZs.

The high seas comprise 64 percent of the ocean’s surface area and host the largest reservoirs of biodiversity on Earth. The number of species they support is enormous, with many more expected to be discovered. And they are getting busier — and becoming more threatened — by the day.

Protection of the high seas has long been overseen by a patchwork of international agencies. As a result, just 1.2 percent of this fragile ecosystem is currently safeguarded against exploitative commercial activity.

As Guy Standing, a professorial research associate at the University of London, told me, there is little reason to believe that the conference would do much to “roll back the power of oligopolistic corporations” in nonterritorial waters. Instead, it would turn out to be just another opportunity for the UN to peddle the narrative that the profit motive, which is largely responsible for destroying the ocean, can spur the necessary action to save it.

As Standing puts it, if we are going to save our oceans, we must reverse their privatization. That means pushing for binding commitments, effective regulation and reliable enforcement. Above all, it means recognizing that the ocean’s true value has no price tag.

Alexander Kozul-Wright is a researcher for the Third World Network.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It

Much like the first round on July 26, Saturday’s second wave of recall elections — this time targeting seven Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers — also failed. With all 31 KMT legislators who faced recall this summer secure in their posts, the mass recall campaign has come to an end. The outcome was unsurprising. Last month’s across-the-board defeats had already dealt a heavy blow to the morale of recall advocates and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), while bolstering the confidence of the KMT and its ally the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). It seemed a foregone conclusion that recalls would falter, as

A recent critique of former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s speech in Taiwan (“Invite ‘will-bes,’ not has-beens,” by Sasha B. Chhabra, Aug. 12, page 8) seriously misinterpreted his remarks, twisting them to fit a preconceived narrative. As a Taiwanese who witnessed his political rise and fall firsthand while living in the UK and was present for his speech in Taipei, I have a unique vantage point from which to say I think the critiques of his visit deliberately misinterpreted his words. By dwelling on his personal controversies, they obscured the real substance of his message. A clarification is needed to