Japan’s minister for gender equality and children’s issues called the country’s record low birthrate and plunging population a national crisis and blamed “indifference and ignorance” in the male-dominated Japanese Diet.

In a wide-ranging interview, Japanese lawmaker Seiko Noda, who is a member of Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s Cabinet, said the steadily dwindling number of children born in Japan was an existential threat, adding that the nation would not have enough troops, police or firefighters in coming decades if it continues.

The number of newborns last year was a record low 810,000, down from 2.7 million just after the end of World War II, she said.

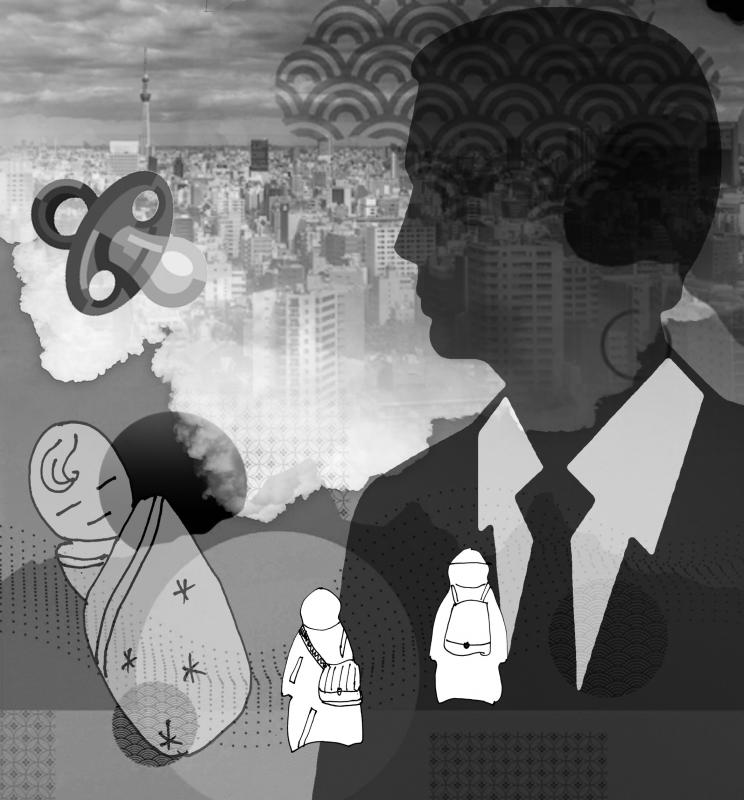

Illustration: Tania Chou

“People say that children are a national treasure... They say that women are important for gender equality, but they are just talking,” Noda, 61, said in a Cabinet office in downtown Tokyo’s government complex. “The politics of Japan will not move unless [the problems of children and women] are made visible.”

She said there are a variety of reasons for the low birthrate, persistent gender bias and population decline in Japan, “but being in the parliament, I especially feel that there is indifference and ignorance.”

Japan is the world’s third-biggest economy, a powerful democracy and a major US ally, but the government has struggled to make society more inclusive for children, women and minorities. There are deep concerns, both within Japan and abroad, about how the country will reverse what critics call a deep-seated history of male chauvinism that has contributed to the low birthrate.

The gap between men and women in Japan is one of the world’s worst. It this year ranked 116th in a 146-nation survey by the World Economic Forum, which measured progress toward equality based on economic and political participation, as well as education, health and other opportunities for women.

“Japan has fallen behind because other countries have been changing faster,” University of Tokyo feminist studies professor Chizuko Ueno said, referring to Japan’s gender gap. “Past governments have neglected the problem.”

Because of outdated social and legal systems surrounding family issues, younger Japanese are increasingly reluctant to marry and have children, contributing to the low birthrate and shrinking population, Noda said.

She has served in the Japanese House of Representatives, the lower house of the Diet, since 1993 and expressed her ambition to be the country’s first female prime minister.

Noda criticized a law requiring married couples to choose one family name — 90 percent of the time it is women who change their surnames — saying it is the only such legislation in the world.

“In Japan, women are underestimated in many ways,” said Noda, who is one of only two women in the 20-member Cabinet. “I just want women to be on equal footing with men, but we are not there yet, and the further advancement of women still has to wait.”

The more powerful lower house is more than 90 percent “people who do not menstruate, do not get pregnant and cannot breastfeed,” she said.

The lack of female representation is often referred to as “democracy without women,” she said.

A quota system could help increase the number of female candidates for political office, she said.

Male lawmakers have criticized her proposal, saying women should be judged by their abilities.

“That made me think that there are men who lack the ability” to be candidates, she said, adding that during the candidate selection process, “men can just be men, and I guess, for them, just being male can be considered their ability.”

Noda graduated from Sophia University in Tokyo and worked at the prestigious Imperial Hotel Tokyo before she entered politics, succeeding her grandfather, who was a lawmaker in central Japan’s Gifu Prefecture.

Noda had her first and only child, who is disabled, at age 50 after fertility treatments. She supports same-sex marriage and acceptance of sexual diversity.

She has many liberal supporters, calling herself “an endangered species” in her conservative Liberal Democratic Party, which has governed Japan with little interruption since the end of World War II.

Noda said she is frequently “bashed” by conservatives in the party, but also by women’s rights advocates, who do not see her as an authentic feminist.

Without the help of powerful male lawmakers in the party, Noda might not have come this far, Mainichi Shimbun editorial writer Chiyako Sato wrote in a recent article.

Comparing Noda with conservative, hawkish female rival lawmaker Sanae Takaichi, Sato wrote that despite their different political views, the women share some similarities.

“Perhaps they had no other way but to win powerful male lawmakers’ backing to advance in the Liberal Democratic Party at a time when women are not considered full-fledged humans.”

One big problem is that the Japan Self-Defense Forces has had trouble getting enough troops because of the shrinking younger population, Noda said.

She said there is also not enough attention paid to what the dwindling numbers will mean for police and firefighters, who rely on young recruits.

To try to address the problems, she has created a new government agency dedicated to children, set to be launched next year.

Younger male politicians in the past few years have become more open to gender equality, partly a reflection of the growing number of children who are being raised by working couples, Noda said.

Many male lawmakers think that issues related to families, gender and population do not concern them, and are reluctant to get involved, she said.

“The policies have been made as if there were no women or children,” she added.

Because much of what former US president Donald Trump says is unhinged and histrionic, it is tempting to dismiss all of it as bunk. Yet the potential future president has a populist knack for sounding alarums that resonate with the zeitgeist — for example, with growing anxiety about World War III and nuclear Armageddon. “We’re a failing nation,” Trump ranted during his US presidential debate against US Vice President Kamala Harris in one particularly meandering answer (the one that also recycled urban myths about immigrants eating cats). “And what, what’s going on here, you’re going to end up in World War

Earlier this month in Newsweek, President William Lai (賴清德) challenged the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to retake the territories lost to Russia in the 19th century rather than invade Taiwan. He stated: “If it is for the sake of territorial integrity, why doesn’t [the PRC] take back the lands occupied by Russia that were signed over in the treaty of Aigun?” This was a brilliant political move to finally state openly what many Chinese in both China and Taiwan have long been thinking about the lost territories in the Russian far east: The Russian far east should be “theirs.” Granted, Lai issued

On Tuesday, President William Lai (賴清德) met with a delegation from the Hoover Institution, a think tank based at Stanford University in California, to discuss strengthening US-Taiwan relations and enhancing peace and stability in the region. The delegation was led by James Ellis Jr, co-chair of the institution’s Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region project and former commander of the US Strategic Command. It also included former Australian minister for foreign affairs Marise Payne, influential US academics and other former policymakers. Think tank diplomacy is an important component of Taiwan’s efforts to maintain high-level dialogue with other nations with which it does

On Sept. 2, Elbridge Colby, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategy and force development, wrote an article for the Wall Street Journal called “The US and Taiwan Must Change Course” that defends his position that the US and Taiwan are not doing enough to deter the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from taking Taiwan. Colby is correct, of course: the US and Taiwan need to do a lot more or the PRC will invade Taiwan like Russia did against Ukraine. The US and Taiwan have failed to prepare properly to deter war. The blame must fall on politicians and policymakers