The soldiers in rural Myanmar twisted the young man’s skin with pliers and kicked him in the chest until he could not breathe. Then they taunted him about his family until his heart ached, too: “Your mom cannot save you anymore,” they said, jeering at him.

The young man and his friend, randomly arrested as they rode their bikes home, were subjected to hours of agony inside a town hall transformed by the military into a torture center. As the interrogators’ blows rained down, their relentless questions tumbled through his mind.

“There was no break — it was constant,” he said. “I was thinking only of my mom.”

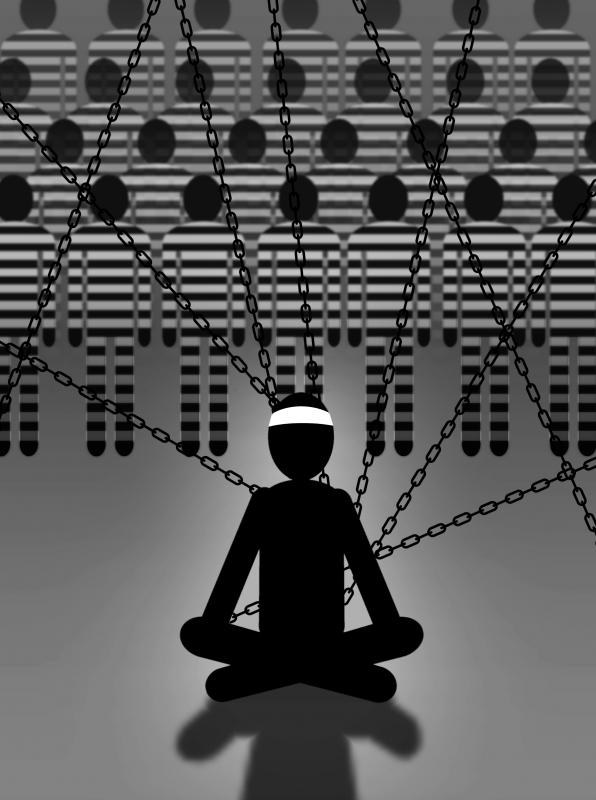

Illustration: Yusha

Since its takeover of the government on Feb. 1, the Burmese military has been torturing detainees across the country in a methodical and systemic way, interviews with 28 people imprisoned and released over the past few months showed.

Photographic evidence, sketches and letters, along with testimony from three defected military officials, provide an in-depth look into a highly secretive detention system that has held more than 9,000 people.

The Burmese military, known as the Tatmadaw, and police have killed more than 1,200 people since February.

While most of the torture has occurred inside military compounds, the Tatmadaw has also transformed public facilities such as community halls and a royal palace into interrogation centers, prisoners said.

A dozen interrogation centers in use across Myanmar, in addition to prisons and police lockups, were identified based on interviews and satellite imagery.

The prisoners came from every corner of the country and from various ethnic groups, and ranged from a 16-year-old girl to monks. Some were detained for protesting against the military, others for no discernible reason. Multiple military units and police were involved in the interrogations, their methods of torture similar across Myanmar.

The prisoners’ names are withheld, or partial names are used, to protect them from retaliation by the military.

Inside the town hall that night, soldiers forced the young man to kneel on sharp rocks, shoved a gun in his mouth and rolled a baton over his shinbones. They slapped him in the face with his own Nike flip-flops.

“Tell me — tell me!” they shouted.

“What should I tell you?” he said helplessly.

He refused to scream, but his friend screamed on his behalf after realizing that it calmed the interrogators.

“I’m going to die,” he told himself, stars exploding before his eyes. “I love you, mom.”

The Burmese military has a long history of torture, particularly before the country began transitioning toward democracy in 2010.

While torture over the past few years was most often recorded in ethnic regions, its use has returned across the country. The vast majority of torture techniques described by prisoners were similar to those of the past, including deprivation of food, water and sleep; electric shocks; being forced to hop like frogs; and relentless beatings with cement-filled bamboo sticks, batons, fists and the prisoners’ own shoes.

However, this time, the torture carried out inside interrogation centers and prisons is the worst that it has ever been in scale and severity, said the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), which monitors deaths and arrests.

Since February, security forces have killed 1,218 people, including at least 131 detainees tortured to death, the group said.

The torture often begins on the street or in the detainees’ homes, and some die before reaching an interrogation center, said AAPP joint secretary Ko Bo Kyi, who is a former political prisoner.

“The military tortures detainees — first for revenge, then for information,” he said. “I think in many ways the military has become even more brutal.”

The military has taken steps to hide evidence of its torture. An aide to the highest-ranking army official in western Myanmar’s Chin State said that soldiers covered up the deaths of two tortured prisoners, forcing a military doctor to falsify their autopsy reports.

Former Burmese army captain Lin Htet Aung, who defected from the Tatmadaw in April, said that the military’s use of torture against detainees has been rampant since its takeover.

“In our country, after being arrested unfairly, there are torture, violence and sexual assault happening constantly,” Lin Htet Aung said. “Even a war captive needs to be treated and taken care of by the law. All of that is gone with the coup. The world must know.”

Lin Htet Aung said that soldiers receive interrogation training, which includes theory, tactics and role play.

He and another former army captain who defected said that the general guidelines from superiors are simply: “We don’t care how you get the information, so long as you get it.”

After receiving detailed requests for comment, military officials responded with a one-line e-mail that said: “We have no plans to answer these nonsensical questions.”

In September, in an apparent bid to improve its image, the military announced that more than 1,300 detainees would be freed from prisons and the charges against 4,320 others pending trial would be suspended.

However, it is unclear how many have been released and how many of those have been rearrested.

All but six of the prisoners interviewed were subjected to abuse, including women and children, while most of those who were not abused said that their fellow detainees were.

In two cases, the torture was used to extract false confessions. Several prisoners were forced to sign statements pledging obedience to the military before they were released. One woman was made to sign a blank piece of paper.

All prisoners who had been held at the same centers gave similar accounts of treatment and conditions, from interrogation methods to the layout of their cells to the exact foods provided — if any.

Photographs of several victims’ injuries were sent to a forensic pathologist with Physicians for Human Rights. The pathologist concluded that wounds on three of the victims were consistent with beatings by sticks or rods.

“You look at some of those injuries where they’re just black and blue from one end to the other,” forensic pathologist Lindsey Thomas said.

“This was not just a swat. This has the appearance of something that was very systematic and forceful,” Thomas said.

Beyond the 28 prisoners, the sister of a prisoner allegedly tortured to death was interviewed, as well as family and friends of current prisoners, and lawyers representing detainees. Sketches that prisoners drew of the interiors of prisons and interrogation centers, as well as letters to family and friends describing grim conditions and abuse, were also obtained.

Photographs taken inside several detention and interrogation facilities confirmed prisoners’ accounts of overcrowding and filth. Most inmates slept on concrete floors, packed together so tightly that they could not even bend their knees.

Some became sick from drinking dirty water only available from a shared toilet. Others had to defecate into plastic bags or a communal bucket. Cockroaches swarmed their bodies at night.

There was little or no medical help. One prisoner described his failed attempt to get treatment for his battered 18-year-old cellmate whose genitals were repeatedly smashed between a brick and an interrogator’s boot.

Not even the young were spared. One woman was imprisoned alongside a two-year-old baby.

Another woman held in solitary confinement at the notorious Insein Prison in Yangon said that officials told her that conditions were made as wretched as possible to terrify the public into compliance.

Amid these circumstances, COVID-19 spread through some facilities, with deadly results.

One woman detained at Insein said that the virus killed her cellmate.

“I was infected. The whole dorm was infected. Everyone lost their sense of smell,” she said.

The interrogation centers were even worse than the prisons, with nights a cacophony of weeping and wails of agony.

“It was terrifying, my room. There were blood stains and scratches on the wall,” one man said. “I could see smudged, bloody handprints, and blood and vomit stains in the corner of the room.”

Throughout the interviews, the Tatmadaw’s sense of impunity was clear.

“They would torture us until they got the answers they wanted,” one 21-year-old said. “They always told us: ‘Here at the military interrogation centers, we do not have any laws. We have guns, and we can just kill you and make you disappear if we want to — and no one would know.’”

Burmese Army Sergeant Hin Lian Piang, who served as a clerk to the Northwestern Regional Deputy Commander before defecting last month, said that glucose drip lines were sometimes attached to the corpses of tortured prisoners to make it look like they had died from something else.

Torture is rife throughout the detention system, Hin Lian Piang said.

“They arrest, beat and torture too many,” he said. “They did it to everyone who was arrested.”

One prisoner, Kyaw, said that he was tortured for days and freed only after signing a statement that he had never been tortured at all.

Kyaw’s hell began when the military surrounded his house and detained him for a second time since February for his democracy activism.

As the soldiers beat him and hauled him away with five of his friends, his mother wet her pants and fainted, while his typically stoic father began to cry.

Kyaw knew what he was thinking: “There goes my son. He’s going to die.”

All the way to the interrogation center in Yangon, soldiers ordered them to keep their heads bowed and beat them with their guns.

When Kyaw’s 16-year-old friend became dizzy and lifted his chin, a soldier bashed his head with a gun until he bled.

At the interrogation center, the soldiers handcuffed them, chained them together and put bags over their heads. His first night was a blur of beatings.

“Rest well tonight,” one soldier told him.

The next morning, none of the detainees could open their swollen mouths enough to eat their rice. It was the only food Kyaw would receive for four days. He drank from a toilet.

His interrogation began at 11am and lasted until 2am or 3am. The soldiers poked his thighs with a knife. They zapped him with a Taser. They rolled iron rods up and down his legs.

They learned that he could not swim, and kicked him into a lake, blinded by the bag on his head and paralyzed by handcuffs that bound his hands behind him.

He thrashed and flailed, sinking ever deeper — they eventually yanked him out.

Their questions were monotonous.

“Who are you and what are you up to?” they asked.

“I really didn’t do anything,” he replied. “I know nothing.”

Another 100 detainees arrived at the center while he was there, some of their faces so disfigured from beatings that they no longer looked human. A few could not walk.

One detainee told Kyaw that soldiers had raped his daughter and her sister-in-law in front of him.

On the fourth day, Kyaw’s family called on a friend with military connections to intervene and the torture stopped, but he was still held for three weeks until the tell-tale swelling in his face went down.

Kyaw was finally released after he paid military officials about US$1,000.

The officials then made him sign a statement saying that the military had never asked for money or tortured anyone.

The statement also said that if he protested again, he could be imprisoned for up to 40 years.

Kyaw does not know if his friends are still alive, but against his mother’s pleas, he has vowed to continue his activism.

“I told my mother that democracy is something we have to fight for,” he said. “It won’t come to our doorsteps just by itself.”

Of the prisoners interviewed, a dozen were women and children, most of who were abused. While the men faced more severe physical torture, the women were more often psychologically tortured, especially with the threat of rape.

Sixteen-year-old Su remembers kneeling with her hands in the air as a soldier told her: “Get ready for your turn.”

She remembers walking between two rows of soldiers while they taunted: “Keep your strength up for tomorrow.”

Su pleaded in vain for soldiers to help one of her fellow inmates — a girl even younger than she was — whose leg was broken during her arrest. The soldiers refused to let the girl call her family.

Prison officials told Su never to tell anyone what had happened to the prisoners.

“They said: ‘We really are nice to you — tell the people the good things about us.’ I asked them: ‘What good things?’” Su said.

Su, who had never been away from her parents, was barred from even calling them and had no idea that her two grandfathers had died.

“As soon as I was released, I had to take sleeping pills for nearly three months,” Su said. “I cried every day.”

Inside Shwe Pyi Thar Interrogation Center in Yangon, the women grew to dread the night, when the soldiers got drunk and came to their cell.

“You all know where you are, right?” the soldiers told them. “We can rape and kill you here.”

The women had good reason to be frightened. The military has long used rape as a weapon of war, particularly in the ethnic regions. During its violent crackdown on the country’s Rohingya Muslim population in 2017, the military methodically raped scores of women and girls.

“Even if they did not rape us physically, I felt like all of us were verbally raped almost every day because we had to listen to their threats every night,” said Cho, an activist detained along with her husband.

One 17-year-old boy endured days of beatings, the skin on his head splitting open from the force of the blows. As one interrogator punched him, another stitched his head wound with a sewing needle. They gave him no pain medication, telling him that the brutal treatment was all that he was worth. His body was drenched in blood.

After three days, they took him to the jungle and dumped him in a hole in the ground, burying him up to his neck, he said, adding that they threatened to kill him with a shovel.

“If they ever tried to arrest me again, I wouldn’t let them,” he said. “I would commit suicide.”

Back inside the rural town hall, the young man ached for his mother as his night passed in a haze of pain. The next morning, he and his friend were sent to prison.

His small cell was home to 33 people. Every inch of floor was claimed, so he lay next to the lone squat toilet.

An inmate gently cleaned the blood from the young man’s eyes. When he looked at his friend’s battered face, he began to cry.

After two days, his family paid to get him out of prison. He and his friend were forced to sign statements saying that they had participated in a demonstration and would now obey the military’s rules.

At home, his mother took one look at him and wept. For a month afterward, his legs and hands shook constantly. Even today, his right shoulder— stomped on by a soldier— does not move properly.

He is constantly on edge. Two months after his release, he realized he was being followed by soldiers. When the sun goes down, he stays inside.

“After they caught us, I know their hearts and their minds were not like the people’s, not like us — they are monsters,” he said.

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Eating at a breakfast shop the other day, I turned to an old man sitting at the table next to mine. “Hey, did you hear that the Legislative Yuan passed a bill to give everyone NT$10,000 [US$340]?” I said, pointing to a newspaper headline. The old man cursed, then said: “Yeah, the Chinese Nationalist Party [KMT] canceled the NT$100 billion subsidy for Taiwan Power Co and announced they would give everyone NT$10,000 instead. “Nice. Now they are saying that if electricity prices go up, we can just use that cash to pay for it,” he said. “I have no time for drivel like

Young supporters of former Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) chairman Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) were detained for posting the names and photographs of judges and prosecutors believed to be overseeing the Core Pacific City redevelopment corruption case. The supporters should be held responsible for their actions. As for Ko’s successor, TPP Chairman Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), he should reflect on whether his own comments are provocative and whether his statements might be misunderstood. Huang needs to apologize to the public and the judiciary. In the article, “Why does sorry seem to be the hardest word?” the late political commentator Nan Fang Shuo (南方朔) wrote

Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi (王毅) reportedly told the EU’s top diplomat that China does not want Russia to lose in Ukraine, because the US could shift its focus to countering Beijing. Wang made the comment while meeting with EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas on July 2 at the 13th China-EU High-Level Strategic Dialogue in Brussels, the South China Morning Post and CNN reported. Although contrary to China’s claim of neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, such a frank remark suggests Beijing might prefer a protracted war to keep the US from focusing on