Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Michelle noticed her teenage daughters were spending substantially more time on Instagram. The girls were feeling isolated and bored during lockdown, the Arizona mom, who asked to only be identified by her first name to maintain her children’s privacy, recalled. She hoped social media could be a way for them to remain connected with their friends and community.

However, as the months progressed, the girls fell into pro-diet, pro-exercise and ultimately pro-eating-disorder hashtags on the social media app. It started with “health challenge” photos and recipe videos, Michelle said, which led to more similar content in their feeds.

Six months later, both had started restricting their food intake. Her eldest daughter developed “severe anorexia” and nearly had to be admitted to a health facility, Michelle said.

Michelle attributes their spiral largely to the influence of social media.

“Of course Instagram does not cause eating disorders,” Michelle said. “These are complex illnesses caused by a combination of genetics, neurobiology and other factors, but it helps to trigger them and keeps teens trapped in this completely toxic culture.”

Testimony from Facebook whistle-blower Frances Haugen last week revealed what parents of teens with unhealthy eating behaviors due to body-image fears had long known: Instagram has a substantial negative impact on some girls’ mental health regarding issues such as body image and self-esteem.

Internal research Haugen shared with the Wall Street Journal found the platform sends some girls on a “downward spiral.”

According to one presentation in March last year about the research, “32 percent of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse.”

Facebook did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but it has disputed the characterization of its internal research on Instagram.

“It is simply not accurate that this research demonstrates Instagram is ‘toxic’ for teen girls,” the company said in a statement last month. “The research actually demonstrated that many teens we heard from feel that using Instagram helps them when they are struggling with the kinds of hard moments and issues teenagers have always faced.”

The company has also criticized the internal presentation that the Wall Street Journal reporting was based on.

However, parents of teens with eating disorders who spoke with the Guardian following Haugen’s testimony said that finding out that Instagram’s parent company had research on Instagram’s impact had been infuriating.

They explained how their children had been directed from videos about recipes or exercise into pro-eating-disorder content and weight-loss progress images. They added that they struggled to regulate their children’s use of social media, which has become inextricable from their kids’ daily lives.

“They are responsible for triggering serious eating disorders in many individuals,” Michelle said about Facebook. “And after what we learned this week, it is evident they don’t care as long as they’re making money.”

‘There is nothing we can do about it,” she said.

Neveen Radwan, a parent living in the San Francisco Bay Area, said social media “has played a humongous role” in her 17-year-old daughter’s eating disorder. The teen had been harmed not only by content that was explicitly pro-anorexia or weight loss, but also by edited photos of influencers and real-life friends, she said.

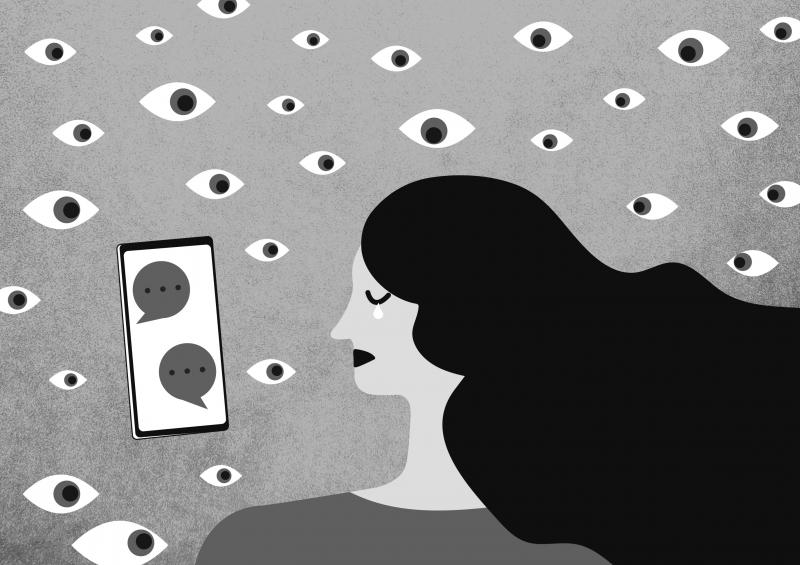

“The second she opens the app, she is bombarded by photos that are filtered, that are manipulated,” Radwan said. “She is trying to attain something that is unachievable.”

Over the past few years, Radwan’s daughter has journeyed down a long road of recovery from a severe eating disorder. At one point, her weight was down to 33.6kg. Her heart stopped beating and she had to be airlifted to a specialized facility.

To help her daughter avoid the triggers she believes helped send her to the hospital, Radwan tried installing a number of safeguards on the girl’s phone. She uses built-in iPhone tools to keep her daughter from downloading apps without permission and monitors her online activity.

Recently, after a year and a half in treatment, Radwan’s daughter was allowed to have her phone back. However, within 30 minutes, the teen had sneaked around the restrictions to log into Instagram from the phone’s browser, Radwan said.

When her daughter had opened the app, her algorithm had been right where she had left it, Radwan said, in the midst of an endless feed of unhealthy eating and diet content.

“Once you look at one video, the algorithm takes off and they don’t stop coming — it’s like dominoes falling,” Radwan said. “It is horrific, and there is nothing we can do about it.”

However, experts say that Facebook could do something about it.

There are a number of proven tools that would prevent the spread of harmful content and misinformation, especially as it relates to eating disorders, said Madelyn Webb, associate research director for Media Matters for America.

Algorithms recommend content similar to what users have shared, viewed, or clicked on in the past — creating a feedback loop that some vulnerable teens cannot escape, she said.

“But they will never change it because their profit model is fundamentally based on getting more clicks,” she said.

Haugen, in her testimony, suggested Facebook return to a chronological rather than algorithmically driven timeline on the platform to reduce the spread of misinformation and inflammatory content.

Facebook has said it works to minimize such content by restricting hashtags that promote it. However, a report released last month by the advocacy group SumOfUs found 22 different hashtags promoting eating disorders still existed on Instagram at the time, and were connected to more than 45 million eating disorder-related posts.

The report found that 86.7 percent of eating disorder posts the researchers analyzed were pushing unapproved appetite suppressants and 52.9 percent directly promoted eating disorders.

Lucy, a mother in the Washington area who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her privacy, said her daughter had struggled with an eating disorder at age 11 and had spent several years in remission.

However, when her social media use started picking up during the COVID-19 pandemic, the eating disorder re-emerged. Lucy said her daughter had changed quickly.

“By the time we found out she was getting this negative body messaging, it was too late — she was already into the eating disorder,” she said. “We watched our smart, lovely, caring, empathetic daughter turn into someone else.”

She has also taken measures to limit her daughter’s social media use — banning her phone from her room at night, restricting time on social media apps and talking to her about responsible use. However, she cannot take away the device completely, as so much of her daughter’s school and social life relies on it.

“Having that phone is like having a 24/7 billboard in front of you that says: ‘Don’t eat,’” Lucy said.

Compounding the problem was the difficulty in finding good and affordable care for teens like her daughter, she said.

“In much of the country there are no therapists. There are waiting lists for treatment facilities, and while you wait, this disease gets stronger, and people get closer to death,” she said.

The rate of eating disorders has risen sharply in recent years, in particular following the onset of the pandemic. A study published by CS Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, found that the total number of admissions to the hospital of children with eating disorders during the first 12 months of the pandemic was more than the average from the previous three years — at 125 young people compared with 56 in previous years.

Meanwhile, access to treatment in the US has remained extremely limited. Hospitals have run out of beds and inpatient treatment centers have long waiting lists.

Despite what many parents see as a direct line between Facebook and Instagram content and their children’s eating disorders, many struggle to leave the platform themselves.

Lucy said she felt “extremely conflicted” about her Facebook usage because the closed groups for parents of children dealing with eating disorders had been “a godsend.”

She recalled a particularly rough day when her daughter lashed out at her after she urged her to eat a small amount of food. Crying and unable to sleep, Lucy posted to the group in the middle of the night in desperation.

“Suddenly dozens of people all over the world who knew what I was going through are telling me — ‘You’ll get through this’ — it made a huge difference,” she said. “It also helps me when I can help other people. Because there is such a stigma around this disease, and this can be such a lonely road.”

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,