On the second floor of a nondescript concrete building in northeast Beijing, the Youyou (優優) Internet cafe is less than half full. Quiet and dark, the cafe’s customers are all adults, sitting in brown sofas in front of screens set up for hours of comfortable online gaming.

Minors are not allowed in, and a poster on the glass entrance reads: “The whole society together cares about the healthy growth of underage teens.”

Under new regulations from the Chinese government, minors are limited to just a few hours of gaming per week, with tech platforms ordered to enforce it. The intervention is just one of a rush of directives from Beijing aimed at reshaping society.

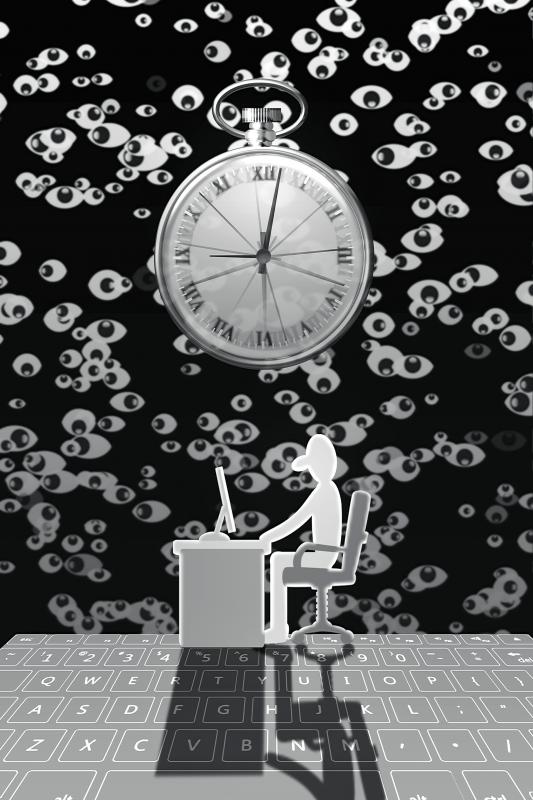

Illustration: Yusha

The slew of regulatory overhauls has been swift and dizzying. In the past few months, Chinese authorities have come for e-commerce, social media, the US$100 billion private education industry, artists, celebrities and reality television, affecting people from Alibaba boss Jack Ma (馬雲) to actor Vicki Zhao (趙薇).

At every step, regulators justified their move as one for the greater social good. Over the past few weeks, the focus has been on celebrity and fan culture, but other sectors have not been forgotten: China’s Internet regulator says it has shut down and banned 1,793 so-called self-media accounts since Aug. 27.

On Wednesday last week, regulators tightened their grip on ride-sharing companies, and separately invited Tencent and Netease — two Internet giants in China — in “for a talk.” The terms of the conversation — relayed by Xinhua news agency, the official state media outlet — name-checked traits being targeted in other areas of the pop culture crackdown, including what has been pejoratively described as “sissyness,” and homosexuality.

The push comes as many among Chinese intelligentsia are expressing their fear of the sort of tight control reminiscent of the pre-reform days. Labeled outside China as “profound,” a “great leap backwards” or a “second Cultural Revolution,” the vast range of new regulations on society are seen by some as an attempt by Chinese president Xi Jinping (習近平) to put his stamp on young minds and cement control.

The crackdown is having a global impact, too. China is one of the world’s biggest markets. As offending industries and people have been targeted, stock markets have turned skittish, major brands have scrapped deals with celebrities, tech and gaming companies have scrambled to navigate new content and distribution laws, and foreign film producers and actors have struggled to navigate the increasingly sensitive market.

In response to concerns about specific moves against the social media accounts of K-pop artists, a hugely successful music genre with an extraordinarily powerful fan base, China’s embassy in South Korea said the crackdown was not targeted at any particular country.

“China’s actions are aimed at all words and deeds that may impact public order — customs as well as laws and regulations — and will not affect normal exchanges between China and any country,” it said on Thursday last week.

Some say these moves were unsurprising and inevitable.

Cao Peixin (曹培鑫) a professor at the Communication University of China, which has trained much of China’s TV talent, said: “Recently there have been frequent occurrences of illegal, wrong or unethical behaviors by celebrities and entertainers in the economic, political and personal fields, which made me feel that the government ... [should] put forward new requirements and norms.”

Cao said there had long been calls from parental groups and social science researchers for an intervention into the “negative impact” of the industry on children, but the industry had used its economic power and media influence to ignore them.

“I believe that the general audience also has dissatisfaction with the bad ethos of the entertainment industry, and the parents of adolescents may have felt it more deeply,” he said.

Last week, the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration asked domestic media to “resolutely resist showing off wealth and enjoyment, hyping up gossip and privacy, negative hot topics, vulgar ‘Internet celebrities’ and the bottomless appreciation of ugliness, and other pan-entertainment tendencies.”

The regulator was also clear that the new measures were designed to create an atmosphere of love for the party and the country, as well as respect for morality and art. They asked producers to include political and moral conduct as criteria in the selection of guests and performers.

In some ways, this reflects the party’s long and complicated relationship with popular culture.

“On the one hand, the party represents the people and wants culture to be popular,” said Michel Hockx, director of the Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies at the University of Notre Dame. “On the other hand, they really don’t approve of what the people seem to like. They consider much of popular culture to be ‘vulgar.’”

The party’s stance on culture and who writers and artists ultimately serve was laid out in a speech by Xi in October 2014.

Artists should not “lose themselves in the tide of market economy nor go astray while answering the question of ‘whom to serve,’” Xi told the forum of artists and writers. “The arts must serve the people and serve socialism.”

Hockx said: “Xi’s 2014 speech was explicit about promoting a kind of culture that could set strong moral examples, as well as promote patriotism. Since then, the various government departments have been trying in various ways to implement these ideas.”

The underlying moral stance under crackdowns on popular culture “is very conservative — a bit like 1950s American TV culture: clearly defined gender roles [with] strong patriotism,” Hockx added.

Bao Hongwei (包宏偉) of the University of Nottingham said that the changes in the ways Beijing handles these issues are related to internal as well as external changes in the past couple of years.

Domestically, China was undergoing a demographic crisis, and Beijing was concerned about the fallout of it, while the increasing antagonism between China and the west has led to a new wave of surging nationalism within China, he said.

“Increasingly, we are seeing — both inside and outside China — the forming of the narrative ‘China versus the west.’ The longer the standoff persists, the more likely Beijing is to emphasize its uniqueness in comparison to the west, or to other Asian countries,” he said.

The changes the authorities wish to pursue might not be easy in today’s China, where decades-long economic opening and societal change have upended traditional norms and rewritten parts of the unspoken social contract between the rulers and the ruled.

“In this process, rules are challenged, negotiated and sometimes consolidated, but they are very much a two-way street,” Bao said.

“The authorities cannot determine everything in today’s China. Time has changed. Things don’t always stay the same and people never give up on their hopes,” he added.

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization