In the past, shareholder votes on the environment were rare and easily brushed aside. Things could look different in the annual meeting season starting next month, when companies are set to face the most investor resolutions tied to climate change in years.

Those votes are likely to win more support than in previous years from large asset managers seeking clarity on how executives plan to adapt and prosper in a low-carbon world, according to interviews with more than a dozen activist investors and fund managers.

In the US, shareholders have filed 79 climate-related resolutions so far, compared with 72 for all of last year and 67 in 2019, data compiled by the Sustainable Investments Institute showed.

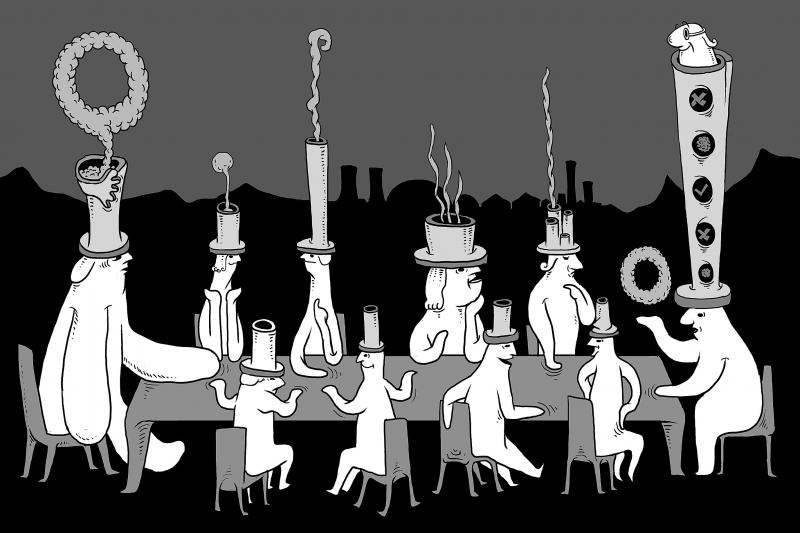

Illustration: Mountain People

The institute estimated the count could reach 90 this year.

Topics to be put to a vote at annual general meetings (AGMs) include calls for emissions limits, pollution reports and “climate audits” that show the financial impact of climate change on their businesses.

A broad theme is to press corporations across sectors, from oil and transport to food and drink, to detail how they plan to reduce their carbon footprints in coming years, in line with government pledges to cut emissions to net zero by 2050.

“Net-zero targets for 2050 without a credible plan, including short-term targets, is greenwashing, and shareholders must hold them to account,” said billionaire British hedge fund manager Chris Hohn, who is pushing companies worldwide to hold a recurring shareholder vote on their climate plans.

Many companies say they already provide plenty of information about climate issues. Yet some activists say they see signs more executives are in a dealmaking mood this year.

Royal Dutch Shell on Feb. 11 said that it would become the first oil and gas major to offer such a vote, following similar announcements from Spanish airports operator Aena, UK consumer goods company Unilever and US rating agency Moody’s.

While most resolutions are non-binding, they often spur changes, with even 30 percent or more support as executives look to satisfy as many investors as possible.

“The demands for increased disclosure and target-setting are much more pointed than they were in 2020,” said Daniele Vitale, the London-based head of governance for Georgeson, which advises corporations on shareholder views.

While more companies are issuing net-zero targets for 2050, in line with goals set out in the 2015 Paris climate accord, few have published interim targets.

A study from sustainability consultancy South Pole (www.southpole.com/news/survey-just-1-in-10-businesses-have-backed-up-net-zero-ambitions-with-science-based-targets) showed just 10 percent of 120 companies it polled, from varied sectors, had done so.

“There’s too much ambiguity and lack of clarity on the exact journey and route that companies are going to take, and how quickly we can actually expect movement,” said Mirza Baig, head of investment stewardship at Aviva Investors.

Data analysis from Swiss bank J Safra Sarasin show the scale of the collective challenge.

Sarasin studied the emissions of the roughly 1,500 firms in the MSCI World Index, a broad proxy for the world’s listed companies. It calculated that if companies globally did not curb their emissions rate, they would raise global temperatures by more than 3°C by 2050.

That is well short of the Paris accord goal of limiting warming to “well below” 2°C, preferably 1.5°C.

At an industry level, there are large differences, the study found: If every company emitted at the same level as the energy sector, for example, the temperature rise would be 5.8°C, with the materials sector — including metals and mining — on course for 5.5°C and consumer staples — including food and drink — 4.7°C.

The calculations are mostly based on companies’ reported emissions levels in 2019, the latest full year analyzed, and cover Scope 1 and 2 emissions — those caused directly by a company, plus the production of the electricity it buys and uses.

Sectors with high carbon emissions are likely to face the most investor pressure for clarity.

Last month, for example, ExxonMobil — long an energy industry laggard in setting climate goals — disclosed its scope 3 emissions, those connected to use of its products.

This prompted the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) to withdraw a shareholder resolution seeking the information.

Simiso Nzima, the head of corporate governance for the US$444 billion CalPERS pension fund, said that he saw this year as a promising year for climate concerns, with a higher likelihood of other companies also reaching agreements with activist investors.

“You’re seeing a tailwind in terms of climate change,” Nzima said.

However, Exxon has asked the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for permission to skip votes on four other shareholder proposals, three related to climate matters, according to filings with the regulator.

It cited reasons such as the company having already “substantially implemented” reforms.

An Exxon spokesman said it had ongoing discussions with its stakeholders, which led to the emissions disclosure.

He declined to comment on the requests to skip votes, as did the SEC, which had not yet ruled on Exxon’s requests as of late Tuesday.

Given the influence of large shareholders, activists are hoping for more from BlackRock, the world’s biggest investor with US$8.7 trillion under management, which has promised a tougher approach to climate issues.

Last week, BlackRock called for boards to come up with a climate plan, release emissions data and make robust short-term reduction targets, or risk seeing directors voted down at the AGM.

It backed a resolution at Procter & Gamble’s AGM, unusually held in October last year, which asked the company to report on efforts to eliminate deforestation in its supply chains, helping it pass with 68 percent support.

“It’s a crumb, but we hope it’s a sign of things to come” from BlackRock, said Kyle Kempf, spokesman for resolution sponsor Green Century Capital Management in Boston.

Asked for more details about its plans for this year, such as if it might support Hohn’s resolutions, a BlackRock spokesman referred to prior guidance that it would “follow a case-by-case approach in assessing each proposal on its merits.”

Amundi, Europe’s biggest asset manager, last week said that it, too, would back more resolutions.

Vanguard, the world’s second-biggest investor with US$7.1 trillion under management, seemed less certain.

Lisa Harlow, Vanguard’s stewardship leader for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, called it “really difficult to say” whether its support for climate resolutions this year would be higher than its traditional rate of backing one in 10.

Hohn, founder of the US$30 billion hedge fund TCI, aims to establish a regular mechanism to judge climate progress via annual shareholder votes.

In a “Say on Climate” resolution, investors ask a company to provide a detailed net zero plan, including short-term targets, and put it to an annual non-binding vote. If investors are not satisfied, they will then be in a stronger position to justify voting down directors, the plan holds.

Early signs suggest the drive is gaining momentum.

Hohn has already filed at least seven resolutions through TCI. The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, which Hohn founded, is working with campaign groups and asset managers to file more than 100 resolutions over the next two AGM seasons in the US, Europe, Canada, Japan and Australia.

“Of course, not all companies will support the Say on Climate,” Hohn told pension funds and insurance companies in November last year. “There will be fights, but we can win the votes.”

Additional reporting by Sonali Paul, Francesca Landini, Clara-Laeila Laudette and Shadia Nasralla

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

In an op-ed published in Foreign Affairs on Tuesday, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) said that Taiwan should not have to choose between aligning with Beijing or Washington, and advocated for cooperation with Beijing under the so-called “1992 consensus” as a form of “strategic ambiguity.” However, Cheng has either misunderstood the geopolitical reality and chosen appeasement, or is trying to fool an international audience with her doublespeak; nonetheless, it risks sending the wrong message to Taiwan’s democratic allies and partners. Cheng stressed that “Taiwan does not have to choose,” as while Beijing and Washington compete, Taiwan is strongest when