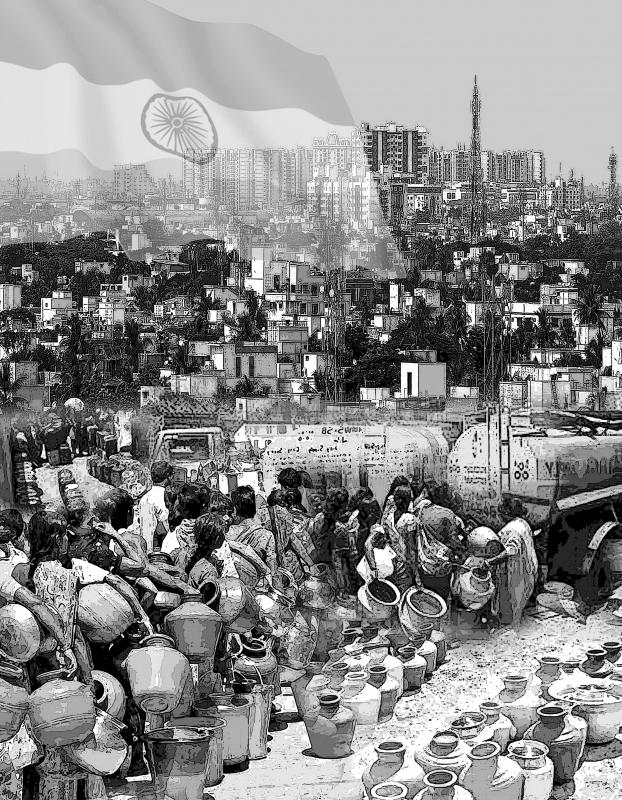

Climate change is bringing rising sea levels and increased flooding to some cities around the world, and drought and water shortages to others. For the 11 million inhabitants of Chennai, India, it is both.

The country’s sixth-largest city gets an average of about 1,400mm of rainfall a year, more than twice the amount that falls on London and almost four times the level of Los Angeles.

Yet in 2019, Chennai hit the headlines for being one of the first major cities in the world to run out of water — trucking in 10 million liters a day to hydrate its population.

Illustration: Constance Chou

This year, it had the wettest January in decades.

The ancient south Indian port has become a case study in what can go wrong when industrialization, urbanization and extreme weather converge, and a booming metropolis paves over its floodplain to satisfy demand for new homes, factories and offices.

Formerly called Madras, Chennai sits on a low plain on the southeast coast of India, intersected by three main rivers, all heavily polluted, that drain into the Bay of Bengal. For centuries, it has been a trading link connecting the near and far east and a gateway to south India.

Its success spawned a conurbation that grew with scant planning and now houses more people than Paris, many of them engaged in thriving automobile, healthcare, information technology (IT) and film industries.

However, its geography is also its weakness.

The cyclone-prone waters of the Bay of Bengal periodically surge into the city, forcing back the sewage-filled rivers to overflow into the streets. Rainfall is uneven, with up to 90 percent falling during the northeast monsoon season in November and December.

When rains fail, the city must rely on huge desalination plants and water piped in from hundreds of kilometers away, because most of its rivers and lakes are too polluted.

While climate change and extreme weather have played a part, the main culprit for Chennai’s water woes is poor planning.

As the city grew, vast areas of the surrounding floodplain, along with its lakes and ponds, disappeared. Between 1893 and 2017, the area of Chennai’s water bodies shrank from 12.6km2 to about 3.2km2, researchers at Chennai’s Anna University say.

Most of that loss was in the past few decades, including the construction of the city’s famous IT corridor in 2008 on about 230km2 of marshland.

The team from Anna University projects that by 2030, around 60 percent of the city’s groundwater would be critically degraded.

With fewer places to hold precipitation, flooding increased.

In 2015, Chennai experienced its worst inundation in a century.

The northeast monsoon dumped as much as 494mm of rain on the city in a single day. More than 400 people in Tamil Nadu state, of which Chennai is the capital, were killed, and 1.8 million were flooded out of their homes. In the IT corridor, water reached the second floor of some buildings.

Four years later it was a shortage of water that made headlines. The city hit what it called “day zero” as all its main reservoirs ran dry, forcing the city government to truck in drinking water. People stood in lines for hours to fill containers, water tankers were hijacked, and violence erupted in some neighborhoods.

“Floods and water scarcity have the same roots: urbanization and construction in an area, mindless of the place’s natural limits,” said Nityanand Jayaraman, a writer and environmental activist who lives in Chennai. “The two most powerful agents of change — politics and business — have visions that are too short-sighted. Unless that changes, we are doomed.”

The Tamil Nadu government predicts in its climate change action plan that the average annual temperature would rise 3.1°C by 2100 from 1970 to 2000 levels, while annual rainfall would fall by as much as 9 percent.

Worse still, precipitation during the June to September southwest monsoon, which typically brings the steady rain needed to grow crops and refill reservoirs, would reduce, while the flood-prone cyclone season in the winter would become more intense. That could mean worse floods and droughts.

The northeast monsoon officially ends in December, but this winter, the heavy rain continued well into January, with Tamil Nadu receiving more than 10 times the normal rainfall for the month.

“Such heavy rainfall was not normal when my parents and grandparents were young,” said Arun Krishnamurthy, founder of Chennai-based nonprofit organization Environmentalist Foundation of India. “People here talk a lot about the weird weather, but they don’t link it to climate change.”

Chennai is an extreme example of a problem that is increasingly disrupting cities around the world that are also grappling with rapid population increases. Beijing, Cairo and Jakarta are among urban centers facing severe water scarcity.

“It’s a global problem, not just Chennai,” Krishnamurthy said. “We need to work together to ensure that we have a water-secure future.”

The state government says that it is addressing the problem. In 2003, it passed a law requiring all buildings to harvest rainwater.

The rule helped raise the water table, but the gains were soon eroded by a lack of maintenance, the Tamil Nadu Central Ground Water Board says.

Efforts to recharge groundwater have also struggled to offset the volume of water being extracted through boreholes.

The Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board and the Tamil Nadu Water Supply and Drainage Board did not respond to questions about the issue.

Shortly after 2019’s day zero, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Edappadi Palaniswami announced a public program that would include a “massive participation of women” covering everything from rainwater harvesting, water saving, and the recycling and protection of water resources, along with studies on how to clean up the state’s polluted rivers.

Until then, the state government’s strategy had centered around the construction of large desalination plants, a costly tactic more commonly associated with arid nations or islands with limited fresh water. The plants have been criticized for causing environmental damage and having a negative impact on local fisheries.

However, the Chennai government is pursuing a new approach inspired by the city’s past.

The Greater Chennai Corp is supporting an initiative called City of 1,000 Tanks, a reference to ancient artificial lakes that were built around temples.

Supported by the Dutch government and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the plan is to restore some temple tanks and build hundreds of new ones with green slopes throughout the city to absorb and filter heavy rains, recharge the groundwater, and store water for use during dry months.

“Floods, drought and sanitation are all interlinked,” said Sudheendra N.K., director of Madras Terrace Architectural Works, which is involved in the project. “When a critical mass of people take up all this, then a significant difference will be noticed and we will no longer be in crisis.”

He said it would take at least five years for the project to have an effect.

Meanwhile, Chennai continues to add about 250,000 people per year, making it a race against time to curb the floods and water shortages.

“My fear is these things will happen more often in the future,” Krishnamurthy said. “We didn’t learn the lesson from day zero.”

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged