US president-elect Joe Biden made a “return to normalcy” one of his election campaign’s leitmotifs. After four years of US President Donald Trump’s bald-faced lies, juvenile bullying, gratuitous cruelty and perilous volatility, it was certainly an appealing promise.

However, as Biden himself has said, the world is not what it was in January 2017, when the administration of then-US president Barack Obama — in which Biden served as US vice president — left office.

So, to what exactly is he planning to return?

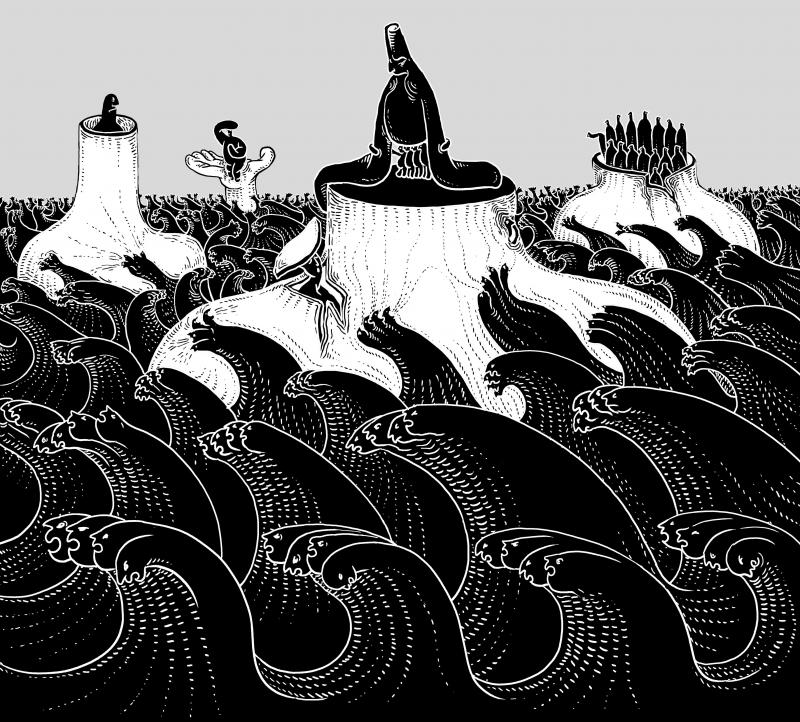

Illustration: Mountain People

To be sure, Biden can certainly restore a sense of decorum and decency to the presidency. However, on concrete policy issues — especially foreign-policy issues — the “status quo” ante would be far more difficult, if not impossible, to revive.

Biden has pledged to recommit to some of the Obama-era international agreements that Trump abandoned, beginning with the Paris climate agreement and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), better known as the Iran nuclear deal.

Moreover, he intends to extend the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with Russia, rejoin the WHO and re-engage with Cuba. He might also join the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the mega-regional trade deal which Obama negotiated and Trump rejected.

Recommitting to the Paris agreement should be the simplest of these actions. It never acquired treaty status, largely because Obama knew that the Republican-controlled US Senate would never approve it.

That is why Trump was able to withdraw from it without a congressional vote; he simply had to abide by the one-year waiting period stipulated in the text. Likewise, Biden could rejoin without congressional approval, after only a 30-day waiting period.

However, the rest of these efforts would be fraught with difficulties.

The JCPOA is a case in point. Although it, too, was not ratified by the senate, unilaterally lifting economic sanctions on Iran (mainly on oil sales) would create a furor among congressional Republicans, whom Biden needs to fulfill other promises. Israel would also be incensed. The move might even raise a few eyebrows in Europe.

Critics have said that the JCPOA imposes insufficient limits on Iran’s nuclear-enrichment capabilities and leaves out critical issues — namely, Iran’s ballistic missiles and, more important, its support for the region’s anti-Israeli, anti-US forces (like Hezbollah) or regimes (such as in Syria). Without some changes, the agreement would most likely remain moribund.

Any effort to reinstate Obama’s normalization policy with Cuba would likely face similar challenges. This approach implies a fully staffed US embassy in Havana, no travel or remittance restrictions, and the revival of cruise ship visits and airline connections. It would also entail as much investment and trade as possible under the US embargo that has been in place since 1961 (which would not be lifted by the Biden administration).

Biden would presumably not ask Cuba for anything in return. After all, Obama in 2015 reached a deal with Havana only because he included no concrete conditions relating to human rights, democracy, economic reform or significant Cuban cooperation in Latin America.

However, as the past five years have shown, Cuba would likely not address these issues on its own. In an interview in September, former US secretary of state John Kerry, speaking on Biden’s behalf, said that Cuba’s progress on human rights and economic reform since 2015 has been “disappointing.”

In fact, human rights conditions have deteriorated and the number of political detainees has increased. The humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, where Cuba wields enormous influence, has worsened considerably, with no solution in sight.

Against this background, attempting to normalize relations with Cuba would be politically risky.

In last month’s US presidential election, Biden performed significantly worse among Cuban-Americans in Miami, which accounts for more than 10 percent of Florida’s voting population, than former US secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton did in her presidential bid in 2016.

Moreover, Biden might need the support of Florida Republicans, such as US Senator Marco Rubio, to fulfill his promise of creating a path to citizenship for up to 12 million undocumented immigrants.

Although Biden has made no promises regarding Venezuela, he might have to make several crucial decisions on this front almost immediately after his inauguration.

Will he maintain economic sanctions against the country and its state-run oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela? Will he recognize Venezuelan National Assembly President Juan Guaido, the opposition leader who last year swore himself in as the country’s interim president, as Venezuela’s legitimate head of state? Will he disregard the results of the farcical National Assembly elections that were held on Sunday last week?

In other words, will Biden broadly uphold Trump’s Venezuela policy (excluding the hare-brained coup schemes concocted by American and local cowboys)? Or will he seek another way to address the country’s severe humanitarian crisis? Returning to Obama’s policy of “benign neglect” — a reasonable position at the time — would today be problematic.

Finally, there is the question of Asia-Pacific trade. Biden has not pledged to join the TPP’s successor, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), created after Trump’s withdrawal by the 11 countries that negotiated the original agreement with Obama. Nor has he announced plans to renegotiate it.

Biden has said that he thought the TPP was not a bad deal for the US, although he might ask for further labor and environmental provisions.

If he wants to revive Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and work with allies to contain China in the region, joining the CPTPP would be a good start.

However, this must be approached less like a return to the past than a step into the future.

Herein lies the fundamental challenge for Biden: How to revive useful multilateral agreements or foreign policies while recognizing the myriad ways the world — and the US’ reputation — has changed in the past four years?

There can be no “returning” to the past, but only adaptation of US objectives and strategies to current conditions. The sooner Biden’s foreign-policy team recognizes this, the better.

Jorge Castaneda, a former Mexican minister of foreign affairs, is a professor at New York University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in