As dark clouds approached her village in northwestern Cambodia one afternoon in July, Set Sreylon prepared for the monsoon that threatened to flood her new family home.

While the rains were a concern, the 37-year-old feared a bigger threat to her property — the daily visits from debt collectors demanding repayments on her microfinance loan and ensuing credit she had taken out to keep up with the repayments.

With the COVID-19 pandemic ending Set and her husband’s jobs in the tourism industry, the mother of two was at a loss as to how she would keep the lenders at bay and clear a growing debt secured by the title to her family’s land.

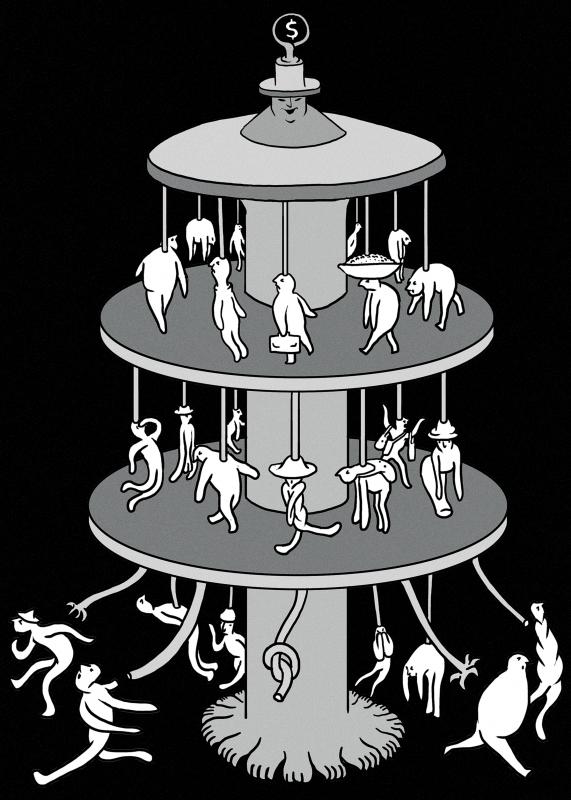

Illustration: Mountain People

Her debt — originally a single loan from a microfinance institution (MFI) — had almost doubled in a year to US$8,000 and was pursued by various loan sharks charging up to 40 percent interest.

“You borrow from A to pay B, then you borrow from B to pay C,” she said outside her home in Pouk district, a few kilometers from Cambodia’s Angkor Wat temple complex and the tourism hotspot of Siem Reap.

“What is the end result? You run out of letters and you have to sell your land,” Set said.

Microfinance was pioneered in the 1970s by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus to give low interest credit to poor or rural people to set up businesses, but the fast-growing sector has been invaded by predatory lenders who can strip people of everything.

Dozens of interviews with indebted villagers, charity staff, economists, lenders and officials revealed how the COVID-19 fallout has compounded microfinance debts, with fears growing that countless Cambodians could end up destitute and homeless.

“The Cambodian microfinance sector was already headed for a meltdown,” said Milford Bateman, a visiting professor of economics at Juraj Dobrila University of Pula in Croatia, and one of the world’s leading academics and authors on the issue.

“COVID-19 has accelerated a slow-moving disaster for the poor as they are gradually stripped of their land,” Bateman added.

Set is far from alone. She holds one of 2.7 million microloans in a country of 3.3 million households, where the average debt per borrower is the world’s highest at US$3,800 — more than twice Cambodia’s GDP per capita.

Since the Southeast Asian nation emerged from decades of war in the 1990s, microfinance has evolved into a US$10 billion sector, profiting international financial institutions.

The model has been credited with helping lift millions out of poverty by funding farming equipment or small businesses, but activists and academics said that it has also driven a rising number of borrowers to sell their land, migrate or put their children to work.

About one in two Cambodians were landless in 2016, up from one-third in 2009, Cambodian government data showed. It is unknown to what extent this rise was fueled by the microfinance industry.

Organizations including the UN and the IMF have in the past few years warned that microfinance poses a risk to the Cambodian economy and ever-bigger loans would only push borrowers deeper into poverty.

Last year, the World Bank said that “deteriorating lending practices and low financial literacy” in Cambodia had helped drive a tenfold increase in average loan size over five years.

High interest rates, the use of land titles as collateral and pressure to repay have led to a “predatory form of lending,” human rights groups Licadho and Sahmakum Teang Tnaut said.

A spokesman for the Cambodian Ministry of Economy and Finance said that the country had a contingency plan for a potential microfinance crash, but did not give details and referred further questions to the Cambodian central bank.

The central bank said it was working to crack down on informal lenders while also running numerous campaigns to boost people’s financial literacy.

“Education is the most sustainable and impactful solution, but takes time to bear fruits,” central bank Director-General Chea Serey said.

She also urged caution over reports about more borrowers falling further into debt.

“As policymakers, we need to be cautious of studies and research that could lead to misleading conclusions,” she added.

Cambodian Microfinance Association (CMA) chairman Kea Borann rejected claims of predatory lending, adding that no land had been seized by any of its 90 members during the pandemic.

To help borrowers, the Cambodian government in 2017 imposed an annual interest-rate cap of 18 percent on MFIs.

However, activists said that lenders responded by imposing new loan fees, covering their losses as debts continued to soar.

Borrowers who are unable to make repayments often double down on MFI loans, or turn to unregulated loan sharks who fly under the radar and offer instant cash at rates as high as 50 percent.

About 45 percent of Cambodians fell deeper into debt from January to April, while one in eight had to sell assets, from livestock and machinery to land, a survey of 54 village chiefs and 1,000 households in five of Cambodia’s 25 provinces showed.

A third of new loans were taken to pay off existing loans or cover living costs, while the proportion of households that borrowed from informal lenders rose to 18 percent from 8.6 percent, the survey by consultancy firm Angkor Research showed.

Dorm Diem, chief of a village whose residents have a combined debt of more than US$250,000, said that debt had led to community tensions and people threatening each other.

“Families are losing everything. Parents are being locked up in Thailand and children are left behind,” he said. “All villages around here are the same.”

“Microfinance has done more harm than good. The problem is only getting worse, and I don’t see how it can be solved,” Dorm added.

One of the villagers, 38-year-old Pherl Pheap, said that several of his neighbors had sold their homes this year to clear their debts and headed to Thailand, willing to risk arrest at closed borders in the hope of finding work.

Official data is lacking, but media reports have detailed the arrests of hundreds of Cambodians trying to cross the border since it was closed in March. About 2 million Cambodians are estimated to work in Thailand, in sectors ranging from fishing to farming.

“It’s a fire sale: sell your house, pay your debts, go to Thailand and start again,” Pherl said. “I am one of the lucky ones. I managed to stay ahead of my debt, but there are others who have borrowed so much that they will never come back.”

While Cambodia has recorded zero deaths and fewer than 300 cases of COVID-19, the pandemic has pummeled the tourism, construction and garment industries that prop up its economy, wiping out hundreds of thousands of jobs.

At least 1.76 million jobs in the nation of about 16 million people are at risk due to COVID-19, while the poverty rate could double, to about one-fourth, the World Bank said in May.

Cambodian human rights groups have called for a freeze on loan repayments due and for lenders to return more than 1 million land titles held as collateral.

Nine major lenders hold 90 percent of Cambodia’s US$10 billion in registered microdebt, including two former MFIs that have since become banks.

Yet the real figure is likely to be far higher, as it does not include microloans given out by dozens of other banks or the growing number of informal lenders, activists and experts said.

Kea said that repayments had been frozen for 25,000 people and 250,000 loans had been restructured to ease pressure on borrowers since March when Cambodia’s COVID-19 outbreak began.

He said reports of MFI staff pressuring borrowers or facilitating land sales were overblown. He pointed to various industry standards — which members are encouraged, but not bound to follow — and a helpline set up to respond to complaints.

Criticism of the sector was unfair, Kea said, as it was based on outdated perceptions of a model that had evolved massively.

While some lenders still offer loans in the development-focused mold — small, non-collateralised sums to kick-start informal businesses — others now approve credit for buying vehicles, building homes or investments, he said.

“People say microfinance is responsible for lifting people out of poverty, but we are not responsible alone,” Kea said. “They need to change the way they look at microfinance in Cambodia.”

The government’s messaging on microfinance has been mixed since the effects of the pandemic provoked widespread alarm.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen in March called upon lenders to restructure loans for people affected by the virus, but later said banks should seize property from those who did not repay.

Chea said that the number of borrowers falling behind on repayments had decreased in July, after almost doubling to 2.72 percent from January to June.

However, advocates said this did not account for a pattern of struggling borrowers taking new loans, often from unregulated loan sharks, to avoid defaulting on official ones where land is collateral.

Cambodian human rights groups have criticized a lack of government oversight, and the role of Western development agencies and foreign investors, including European state development banks, for failing to address concerns.

From their roots in poverty alleviation, the nine major lenders are now almost all completely owned by international financial institutions and driven by profits, Licadho said.

“Development actors ... have failed to ensure programs they fund do no harm, and Cambodian borrowers are currently paying the price for that failure,” Licadho director Naly Pilorge said. “Money that goes to further loans, without reforming the sector, will just compound the over-indebtedness crisis.”

In June, the International Finance Corporation — which focuses on the private sector in developing countries — approved US$75 million in COVID-19 relief funds to be dispersed as loans by two Cambodian MFIs.

Another major MFI, LOLC Cambodia — formerly known as Thaneakea Phum or Village Bank — posted net profits exceeding US$21 million in the first half of this year, up from US$17.6 million last year.

LOLC’s parent company — The LOLC Group, Sri Lanka’s most profitable listed business — last year agreed to sell its 70 percent stake in Cambodia’s biggest microlender, Prasac Microfinance Institution, for US$603 million, marking a large profit.

“The main beneficiaries of microcredit in Cambodia are quite clear,” Bateman said. “They are the CEOs and senior managers of the leading MFIs, and their core shareholders and wealthy foreign investors, who ... have been making out like bandits.”

LOLC and other shareholders in Cambodian MFIs — such as PhillipCapital Group, Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank, Bank of Ayudhya, Netherlands Development Finance and the European Investment Bank — largely did not reply to requests for comment.

German state-owned development bank KfW said it is to look into reports of improper MFI lending and forced land sales in Cambodia.

Loan officer Chea Chantha spends his days door-knocking, chasing repayments and convincing people to take out new loans from his employer, a registered lender. He said that clients defaulting and losing their land was a routine part of the job.

“When you get a loan, you know the conditions,” Chea Chantha said, adding that he often reads aloud the fine print of loan contracts to illiterate clients.

“If you sign, you agree. If you cannot afford repayments, of course you will lose your property,” he said.

The CMA said about 60 percent of microloans in Cambodia are collateralized, the majority by land titles. Yet the association said that its members rarely took land held as collateral from defaulting borrowers and had not done so at all since March.

However, activists detailed an off-the-books tactic whereby borrowers were persuaded to sell their land before it was taken.

Formal land seizures go through the courts so lenders tell clients to sell privately and use the money to avoid defaulting, shielding both parties from legal fees, Licadho said.

This process, often accompanied by the promise of a new loan, allows the borrower to retain a good credit rating and saves the lender from bad publicity, a report coauthored by Licadho said, anonymously quoting two MFI industry executives.

Local officials are often a party to loan contracts, and lenders cooperating with authorities to increase pressure on borrowers is “widespread,” the report said.

Brokering agreements between lenders and borrowers was now an unwanted, but regular part of his role, Dorm said.

“First, it is US$5,000, then US$10,000, then US$20,000 — then you say goodbye,” he said, adding that about one-third of 134 homes in his village were up for sale or had been sold to repay debts.

One of the villagers, 35-year-old Nan Sarin — who fell into debt with a US$3,000 loan taken to hold a religious ceremony for her ailing parents — described having to sell off the family’s farmland piece by piece as their debt diversified and soared.

“The stress of it all could kill me,” she said, nursing one child as two others listened to her describe her financial woes.

“We do not see any progress in society from these loans — only misery and debt,” she added.

Chinese actor Alan Yu (于朦朧) died after allegedly falling from a building in Beijing on Sept. 11. The actor’s mysterious death was tightly censored on Chinese social media, with discussions and doubts about the incident quickly erased. Even Hong Kong artist Daniel Chan’s (陳曉東) post questioning the truth about the case was automatically deleted, sparking concern among overseas Chinese-speaking communities about the dark culture and severe censorship in China’s entertainment industry. Yu had been under house arrest for days, and forced to drink with the rich and powerful before he died, reports said. He lost his life in this vicious

In South Korea, the medical cosmetic industry is fiercely competitive and prices are low, attracting beauty enthusiasts from Taiwan. However, basic medical risks are often overlooked. While sharing a meal with friends recently, I heard one mention that his daughter would be going to South Korea for a cosmetic skincare procedure. I felt a twinge of unease at the time, but seeing as it was just a casual conversation among friends, I simply reminded him to prioritize safety. I never thought that, not long after, I would actually encounter a patient in my clinic with a similar situation. She had

A recent trio of opinion articles in this newspaper reflects the growing anxiety surrounding Washington’s reported request for Taiwan to shift up to 50 percent of its semiconductor production abroad — a process likely to take 10 years, even under the most serious and coordinated effort. Simon H. Tang (湯先鈍) issued a sharp warning (“US trade threatens silicon shield,” Oct. 4, page 8), calling the move a threat to Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” which he argues deters aggression by making Taiwan indispensable. On the same day, Hsiao Hsi-huei (蕭錫惠) (“Responding to US semiconductor policy shift,” Oct. 4, page 8) focused on

George Santayana wrote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This article will help readers avoid repeating mistakes by examining four examples from the civil war between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forces and the Republic of China (ROC) forces that involved two city sieges and two island invasions. The city sieges compared are Changchun (May to October 1948) and Beiping (November 1948 to January 1949, renamed Beijing after its capture), and attempts to invade Kinmen (October 1949) and Hainan (April 1950). Comparing and contrasting these examples, we can learn how Taiwan may prevent a war with