If you try to contact Indy Cube, a provider of workspaces in Wales, after 5pm you receive an automatic message that would make a good manifesto for the fast-growing four-day week movement.

“We’ll get back to you pretty quickly during working hours,” it says. “If you’re messaging us outside of these, we’re probably busy with other things, like horse-riding, karate, or good ole fashioned sleep.”

The firm is one of a growing number of employers in the UK giving their workers an extra day off for the same pay as a five-day week. There is emerging evidence that it can boost productivity for bosses and happiness for workers.

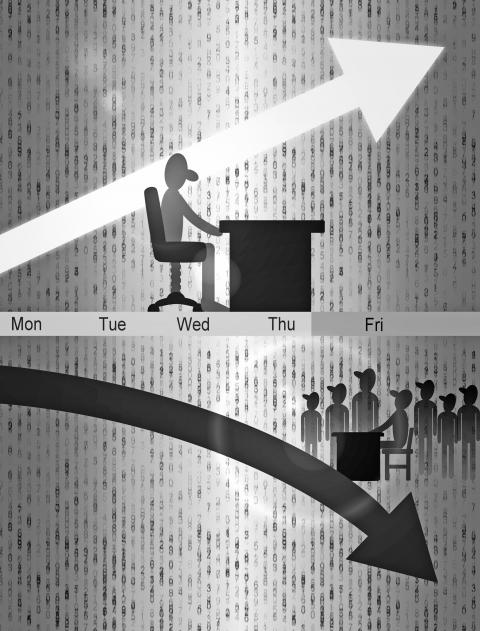

Illustration: Yusha

Playgrounds, garden centers and gymnasiums are filling up on Fridays with people extending their leisure into a five-day working week that has been a staple of Western culture since Henry Ford adopted it in 1926.

It is not just small businesses that might be spotting a chance to save a little money by turning the lights off one day a week.

Pursuit Marketing, a marketing company in Glasgow, Scotland, that switched 120 people to four days in late 2016, claims that it has been instrumental to achieving a 30 percent increase in productivity.

Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand trust business that supervises nearly NZ$200 billion (US$137.04 billion) in assets, has switched its 240 employees to a four-day week and has reported a 20 percent increase in productivity.

PRODUCTIVITY

A string of small businesses in the UK contacted the Guardian to enthuse about higher productivity, greater staff satisfaction and even bigger profits. Talk of family lives reinvigorated and stress levels plunging abounded.

In January, the Wellcome Trust became the biggest UK employer to join the trend when it announced that it was exploring switching 800 head office staff to a three-day weekend.

The UK Labour Party is flirting with how the idea could fit into its policy program: Shadow chancellor of the exchequer John McDonnell has commissioned leading economist Robert Skidelsky to investigate.

And yet, for all the excitement that the world might finally be moving toward John Maynard Keynes’ 1930 vision that by now all people would have a 15-hour week and spend the rest at leisure, most people who want to work less simply cannot.

Since the financial crisis, people in the UK have been working longer, not shorter, hours as stagnating wages have seen employees try to take on more work to keep up with inflation.

In 2011, decades of falling hours went into reverse and Britons started working longer again. If the trend of falling hours had continued, they would be enjoying the equivalent of an extra week-and-a-half’s free time each year by now.

Automation and artificial intelligence, billed as drivers of greater leisure, have been harnessed by the barons of the gig economy to the opposite effect for some workers.

Many of the 1.1 million self-employed people who access work through online platforms such as food delivery app Deliveroo and ride-hailing platform Uber, as well as white-collar apps such as Upwork, are squeezing ever more tasks to keep their earnings in line with the cost of living.

They face periods at work with no pay at all, such as waiting for a taxi fare or for parcels to be collated before delivery.

“The economic fundamentals are going against the grain of the politics of hours reductions,” said Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation think tank. “Our object should be to get them on track.”

A growing number of people are trying to do just that.

Pursuit Marketing is in the hip west Glasgow area of Finnieston and is a typical part of Britain’s service-driven economy. Pursuit’s 120 workers staff a call center and digital marketing operation selling services on behalf of technology companies such as Google, Microsoft, Oracle and Sage. Since 2011 they have worked a regular week — 8:45am to 5pm Monday to Thursday, and a shorter day on Friday, ending at 3:30pm.

However, in September 2016, managers wanted to increase workers’ productivity. They had noticed that workers on reduced hours to fit in school runs or look after family dependents were making about 17 percent more sales than the full-timers.

“The time off was valued, so they wanted to make sure they could keep it and they would attack their day,” Pursuit director Lorraine Gray said. “They were clear in their focus and there was less small talk by the water cooler.”

The firm cut everyone’s working week to Monday to Thursday, without changing pay.

She said staff responded with “a lot of noise, a lot of excitement” as the new working week took hold.

In the first four weeks, sales spiked by 37 percent.

“People thought: If we can make this work, we can keep it,” Gray said.

The increased productivity has since stabilized and turnover is up 29.5 percent after two years, the majority of which Gray said she attributes to the switch to a four-day week.

Clients also appear to like the four-day week, because staff with whom they have built relations are less likely to leave, she said, adding that just two left over the last 12 months.

Recognizing that water-cooler chats are still an important part of work, the firm offers free pre-shift breakfasts, so workers can spend a little time gossiping before business begins.

Jon Freeman, 33, a traveling salesman for the firm, said that the new work schedule has given him more energy while at work.

He gets to look after his boys aged two and five every Friday, and his wife, Clare, is free to take on more hours in her work as a pharmacy dispenser, he said.

“I am more focused and driven because I appreciate the extra time off,” he said. “I used to really watch the clock at the weekend, because I never felt like I had long enough off, but now when I come back on Monday, I really attack it.”

One of the biggest organizations to make the switch is Perpetual Guardian, whose shift has generated huge global interest, with 400 organizations from around the world asking it for advice.

“This week we have had people contact us from Japan, Canada, the UK, France, Switzerland,” Perpetual founder and chief executive Andrew Barnes said. “The week before it was Bulgaria.”

The day off that each worker takes varies, depending on the team’s needs at the time, but there has been a change in culture with “less time surfing on social media, fewer unnecessary meetings,” Barnes said.

Staff have taken to putting flags in pots on their desks as “do not disturb” signs, he said.

“This is an idea whose time has come,” said Barnes, a four-day week evangelist, adding that he had spotted “a chance to change the world.”

“We need to get more companies to give it a go. They will be surprised at the improvement in their company, their staff and in their wider community,” Barnes added.

He said it helps to level the playing field between women and men, partly by making it easier for mothers returning to work, because they do not need to commit to five days, and by making men more available for domestic duties.

MORE TIME

Research into what people might do with more time has produced some bracing results.

A 2010 study by US economic psychologists investigated how 909 women would schedule a 16-hour day to maximize wellbeing. Only 36 minutes were allocated for work, compared with 106 minutes for “intimate relations,” 82 minutes for socializing and 56 minutes for shopping.

Maybe more “intimate relations” would be good for the economy.

Britons work on average 1,514 hours each annually, a full four weeks more than in Germany, but are less productive.

Germans and Americans produce GDP worth US$60.50 and U$64.10 respectively for each hour they work, compared with US$53.50 in the UK.

“Productivity relies not just on the sheer amount of hours put in, but on the wellbeing, fatigue levels and overall health of the worker,” Autonomy, a new consultancy and think tank examining the shorter working week, said in February.

Productivity drops after the 35th hour of weekly work, a 2014 study for the Institute for Labour Economics found.

A study of call centers found that calls were handled less efficiently the longer people worked.

When they work shorter hours, people tend to be more relaxed — and more productive.

However, Bell, a former UK Treasury adviser under the Labour Party, is one of those who are skeptical that productivity gains would be enjoyed across the economy.

“It is very hard to assert that overall output will rise if you cut 20 percent of your hours across the economy as a whole,” he said.

Talk-radio host Nick Ferrari put it more bluntly when he said that it is “an insane notion.”

Meanwhile, the Confederation of British Industry, which represents major employers, is unmoved by a four-day week.

“At a time when flexible working is becoming more essential than ever, rigid approaches feel like a step in the wrong direction,” a spokesman said. “Businesses are clear that politicians should work with them to avoid policies that work as a soundbite, but not a solution.”

Skidelsky’s review is certainly finding it complicated.

PRESENTEEISM

Rachel Kay, a researcher on the project, said that working fewer hours for the same money could work in task-focused sectors where employers do not need people available all the time, but is less likely in, for example, retail — the UK’s biggest employer — where presenteeism is required.

“A common complaint after France’s move to the 35-hour week was that companies intensified work to an unpleasant degree, making work more stressful,” she said. “So whether a shorter working week without new hires would result in improved wellbeing for employees depends on the existing workloads in any given workplace.”

“If we all shut up shop on Thursday, what do we do on the weekend?” said Kate Cooper, policy director at the Institute of Leadership and Management. “Unless, like the Swedes, we go and commune in the woods, we need other people to be working. So who is the four-day week for?”

“I am desperately trying to see how this isn’t going to be for the privileged few. [In] anything that is customer-facing, or involving a dynamic or volatile environment, you don’t have the luxury,” Cooper said.

The reasons behind increases in productivity are not yet clear.

Cooper said that “the Hawthorne effect” might be in play: People change their behavior simply because they feel that they are being observed.

In this case, people might feel that being granted a four-day week shows that their bosses are interested in their work.

“How sustainable is that?” Cooper said. “Where does the lovely feel-good factor come from if everybody is doing it?”

She also had reservations about what might be lost by the removal of the fifth day of the working week.

“What is being pushed out? What was happening on that fifth day? Were people forming strong social bonds?” she said. “Were they getting a sense of the company culture?”

“If work is just about getting a job done, a list of tasks, then the sense of purpose and social bonding that comes from employment might not be there,” Cooper added.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a

A recent piece of international news has drawn surprisingly little attention, yet it deserves far closer scrutiny. German industrial heavyweight Siemens Mobility has reportedly outmaneuvered long-entrenched Chinese competitors in Southeast Asian infrastructure to secure a strategic partnership with Vietnam’s largest private conglomerate, Vingroup. The agreement positions Siemens to participate in the construction of a high-speed rail link between Hanoi and Ha Long Bay. German media were blunt in their assessment: This was not merely a commercial win, but has symbolic significance in “reshaping geopolitical influence.” At first glance, this might look like a routine outcome of corporate bidding. However, placed in