As British politicians confront the threat of a chaotic Brexit and calls for a rerun of the 2016 referendum, the china plates in parliament’s tearooms carry a timely reminder of the perils of democracy: “Made in Stoke-on-Trent.”

The city, once the heart of the world’s pottery industry, is a potent symbol of the gulf between politicians and the people who put them in power. Left behind by globalization and neglected by successive governments, no city voted for Brexit more emphatically.

The mood in Stoke encapsulates the risks facing politicians of all stripes with the country in turmoil over how to follow through on the vote to leave the EU.

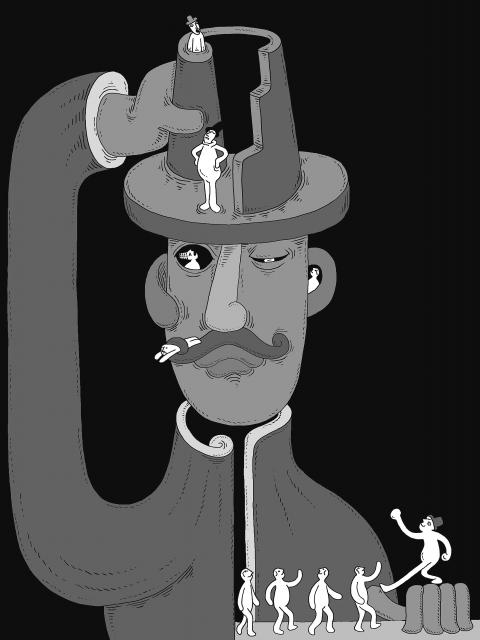

Illustration: Mountain People

Brexit is due at the end of March and British Prime Minister Theresa May’s deal is on course for a catastrophic defeat in parliament. A growing number in her Conservative Party believe the only way out of the crisis is to call another vote.

Time and a divided electorate’s patience are running out, while the political climate grows more febrile.

Pockets of protesters at Westminster have become the norm, but last week it got nastier as one member of parliament was jostled and called a Nazi for backing a second referendum to break the national impasse.

Some people in Stoke say politicians need to think hard about what they might unleash.

“There would be violence all over the country, far left, far right, skinheads,” said Kevin McCormack, 59, standing along from a parade of stores in the Stoke suburb of Bentilee, which is statistically among the 10 percent most deprived neighborhoods of England. “All these MPs [members of parliament] work for us supposedly, they’re supposed to do what we ask them. People are sick and tired of being told what we can and can’t do.”

These are dark days in Britain. The financial crisis and ensuing government austerity drive left their mark on the country. Then the Brexit vote threw up the opportunity for a populist rebellion and a cry for help. The nation was split 52 to 48 percent in favor of leaving the EU.

What followed was political inertia as the UK got consumed by the process of negotiating an exit deal. Now comes more anger and resentment while the prospect of an economically ruinous “no-deal Brexit” increases.

It helps explain why even some of those who want to remain in the EU are skittish about a second referendum, which would become an urgent question if, as expected, May’s deal is defeated and parliament wrests control of the Brexit process from her minority government.

For two years, anti-Brexit campaigners have been pinning their hopes on a another vote to overturn the result of the first. Now, with the House of Commons deadlocked and the UK’s exit just two months away, even May sees that it might happen as a national campaign for a “People’s Vote” gathers pace.

However, would a new referendum heal the wounds of a country already at war with itself? May has repeatedly cited first-time voters who would feel betrayed when she has rejected pleas from parliamentarians to hold another vote. There is palpable fear over what might happen if the electorate’s wishes are frustrated.

The bitterness comes through in Stoke, where gross weekly pay is 16 percent lower than the UK average and a greater proportion of people is likely to rely on social security handouts.

Almost 9,000 more people turned out to vote in the referendum than in the general election a year earlier. Just short of 70 percent chose to leave, more than any other British city. Now they want to see results.

“These are people who felt disenfranchised from the political process — they’ve opted in and are now waiting to see if there’s any point,” said Ruth Smeeth, the MP for Stoke North.

She opposes a second referendum, even though her Labour Party has said it might support one if it cannot trigger a general election.

“If it looks like the political elite are willfully ignoring the majority of the general public, they’ll stop trusting politicians, and when that relationship breaks down nothing good comes from it,” she said.

Indeed, nationalist groups have sought to exploit the anger. Far-right advocate Tommy Robinson, an adviser to the pro-Brexit UK Independence Party, used his social media following to build support for marches on the streets of London that led to clashes with police and counterprotesters.

The 2016 referendum campaign itself is also remembered in Britain for the brutal murder of Jo Cox, a pro-EU Labour MP. She was killed by a far-right extremist a week before the vote. Several politicians have received death threats since. A spike in hate crimes was recorded immediately after the Brexit referendum and has been on an upward trend since.

“It’s the coarsening of political debate that’s occurred as result of the move to the extremes on both sides of the debate in the UK,” said Guto Bebb, a member of the governing Conservative Party who resigned as a minister over Brexit and has had people protesting outside his home.

He blamed Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn for allowing tensions to flare up on the left of the political spectrum.

“And Brexit has done the same for the right,” Bebb added.

This week, police stepped up their presence around parliament after pro-EU Conservative Anna Soubry was mobbed and called a Nazi on live television. Although May condemned the abuse, British Secretary of State for Exiting the EU Stephen Barclay said that the incident was another reason to avoid a second EU referendum.

A survey of 2,158 adults by YouGov in October last year found that 31 percent thought there was a risk of “civil unrest” should there be another vote and Britain failed to leave the EU. The figure was 50 percent among Brexit voters.

That said, among Stoke’s 270,000 population, there is a mix of anger and apathy. The risk is that voters energized by Brexit might just give up.

“What’s the point?” asked Kenneth Runt, 48, an engineer doing some grocery shopping in the district of Bentilee, which was developed in the 1950s and was one of Europe’s largest housing projects at the time. “If they don’t get the result they want they’ll just have another one.”

Brenda Wilson, 72, a retired saleswoman with dyed blond hair and leopard-print winter coat, said that people would not bother voting again.

“They’ve got to get on with it,” she said outside discount store Poundland in central Stoke. “It drives me crackers. I’m sick of hearing about it. They’re supposed to be clever people and they’re earning a lot of money and they can’t get it together.”

While polls show growing support for a second referendum across the country, Stoke does not seem to be budging. Three-quarters of the e-mails Smeeth received from constituents over the Christmas holidays urged her to support leaving the EU on March 29, regardless of whether May’s Brexit deal is passed in parliament.

The city’s struggle to adapt to economic change has driven opposition to the EU and its commitment to free movement of people, which has allowed migrant workers, particularly from eastern Europe, to enter the labor market. The ceramics industry, which employed 50,000 a generation ago, is now down to just 7,000 people.

A decade ago, the far-right British National Party (BNP) won seats in Stoke’s municipal government as voters protested they had been ignored by politicians from mainstream parties.

Smeeth, a former director of an anti-extremist group, said that parties across the country need to re-engage with voters to stop history being repeated.

“We created the BNP, we allowed a vacuum and they filled it,” she said. “That’s why we’ve got such a responsibility in this unsettling period of our national story.”

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

Liberals have wasted no time in pointing to Karol Nawrocki’s lack of qualifications for his new job as president of Poland. He has never previously held political office. He won by the narrowest of margins, with 50.9 percent of the vote. However, Nawrocki possesses the one qualification that many national populists value above all other: a taste for physical strength laced with violence. Nawrocki is a former boxer who still likes to go a few rounds. He is also such an enthusiastic soccer supporter that he reportedly got the logos of his two favorite teams — Chelsea and Lechia Gdansk —