Last month, a deeply divided Brazil voted to elect its next president. Faced with a choice between Fernando Haddad of the leftist Workers’ Party and the rightwing extremist Jair Bolsonaro, Brazilians chose the extremist — an outcome that will have far-reaching consequences for the environment, among other things.

With solid backing from the wealthiest 5 percent of Brazilians and rural landowners, Bolsonaro secured broader popular support by playing on people’s prejudices and fears.

In his campaign, he targeted vulnerable groups and pledged to reduce or eliminate protections for minorities, women and the poor.

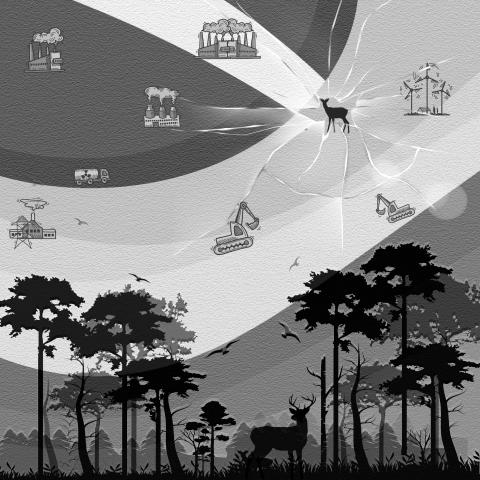

Illustration: June Hsu

Meanwhile, he intends to loosen Brazil’s restrictive gun laws, claiming that allowing average citizens to arm themselves will stem rising crime.

As for the environment, Bolsonaro’s plans can be summed up in one word: exploitation.

For starters, he wants to reduce or eliminate environmental protections in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest.

He intends to reduce substantially the protection of indigenous lands belonging to the descendants of the Amazon’s original inhabitants.

He also plans to ease environmental restrictions on the use of pesticides and on licensing for infrastructure development.

“Where there is indigenous land, there is wealth underneath it,” Bolsonaro once said.

With that in mind, he has declared that no more indigenous reserves will be demarcated, and existing reserves are to be opened up to mining.

Bolsonaro’s agenda will hasten environmental degradation dramatically.

Imazon, a Brazilian NGO, reported 444km2 of clearing in September, an 84 percent increase over September last year. The 12-month total amounts to 4,859km2, the highest level since July 2008.

Brazil’s national space research agency, INPE, also reports an uptick in deforestation — about 50 percent year on year in September.

As it stands, many of the farmers or loggers who exploit the Amazon do so illegally, risking fines or sanctions.

The expectation that the new government will not enforce laws prohibiting such activities is probably already emboldening them to intensify their activities.

Once those laws are weakened or abolished, deforestation can be expected to accelerate considerably. The government’s apparent inclination to boost activities like gold mining in the Amazon will only make matters worse.

There is little reason to believe that Bolsonaro will not be able to follow through on his destructive environmental agenda.

After all, far-right representatives allied with powerful business lobbies dominate Brazil’s new congress.

To make destroying the environment even easier, Bolsonaro has pledged to merge the environment and agriculture ministries, though he has since backtracked on this issue.

He is now looking for an environment minister who is allied with the ruralistas, or large landowners, and has appointed a minister of agriculture who wants to lift restrictions on the use of dangerous chemical products in agriculture.

Bolsonaro also promised during the election campaign to withdraw Brazil from the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

Alhough he has since backed away from that pledge, he has just appointed a climate-change-denying, anti-science diplomat as foreign minister.

That will present certain difficulties for Brazil’s bid to host the UN Climate Change Conference next year.

Beyond increasing the vulnerability of Brazil’s natural resources to commercial exploitation, the inevitable cuts to the environmental budget under Bolsonaro’s leadership will undermine the country’s ability to respond to disasters such as forest fires.

Brazil has already had an uptick in such fires — and fire-related destruction — owing to the expansion of agriculture, weaker oversight and surveillance, and the dismantling of fire brigades.

Bolsonaro’s plans will exacerbate the problem.

This is not the only problem that Bolsonaro’s agenda will worsen.

Socioeconomic inequality will increase. As the government hands more power over the rainforest to large business owners, ordinary citizens — including smallholder farmers and poor urban dwellers — are bound to suffer.

However, Brazil’s ecosystems matter for more than just that country — it is the guardian of the planet’s largest tropical rainforest, a repository of ecological services for the entire world, where most of the Earth’s biodiversity is concentrated.

The Amazon is home to more species of plants and animals than any other terrestrial ecosystem on the planet, and its rainfall and rivers feed much of South America.

Moreover, its hundreds of billions of trees store massive amounts of carbon.

Over the past 100 years, Brazil has reduced the Atlantic Forest by more than 90 percent, and cleared 50 percent of the Cerrado and almost 20 percent of the Amazon.

At a time when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is warning that we need to make urgent progress in reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, Bolsonaro’s plans will achieve just the opposite.

Unfortunately for Brazil and the rest of the world, there is no reason to believe that he cannot or will not implement them.

Paulo Artaxo is professor of environmental physics at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, and head of its applied physics department. He is an expert on the climatic effects of aerosols, particularly in Amazonia.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its