Shortly after US President Donald Trump announced in May that he would reimpose sanctions on Iran, the US Department of State began telling countries around the world the clock was ticking for them to cut oil purchases from the Islamic Republic to zero.

The strategy is meant to cripple Iran’s oil-dependent economy and force Tehran to quash not only its nuclear ambitions, but this time, its ballistic missile program and its influence in Syria.

With just days to go before renewed sanctions take effect on Monday, the reality is setting in: Three of Iran’s top five customers — India, China and Turkey — are resisting Washington’s call to end purchases outright, saying that there are not sufficient supplies worldwide to replace them, according to sources familiar with the matter.

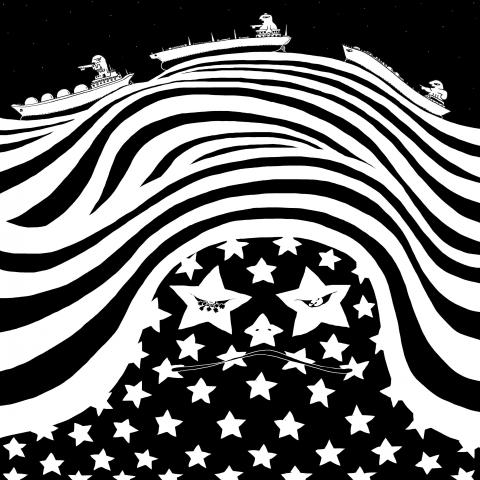

Illustration: Mountain People

That pressure, along with worries of a damaging oil price spike, is putting the Trump administration’s hard line to the test and raising the possibility of bilateral deals to allow some buying to continue, according to the sources.

The tension has split the US administration into two camps, one led by US National Security Adviser John Bolton, who wants the toughest possible approach, and another by department officials keen to balance sanctions against preventing an oil price spike that could damage the US and its allies, according to a source briefed by administration officials on the matter.

The global price of oil last month peaked just below US$87 a barrel, a four-year high.

Because of that concern, the source said, the US administration is considering limited waivers for some Iranian customers until Russia and Saudi Arabia add additional supply next year, while limiting what Tehran can do with the proceeds in the meantime.

Revenues from sales could be escrowed for use by Tehran exclusively for humanitarian purposes, the source, who asked not to be named, said — a mechanism more stringent than a similar one imposed on Iran oil purchases during the last round of sanctions under former US president Barack Obama.

“If you’re the administration, you’d like to ensure you don’t have a spike in the price. So, you are better off from mid-2019 onwards to aggressively enforce the barrels side of reducing to zero and in the interim aggressively enforcing the revenue side,” the source said.

Such concessions could be problematic for the White House as it seeks stricter terms than under Obama, who along with European allies imposed sanctions that led to an agreement limiting Iran’s nuclear weapons development.

The department declined comment for this story, but the US administration has confirmed that Washington is considering waivers.

US Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin told reporters that countries will first have to reduce purchases of Iran’s oil by more than the 20 percent level they did under the previous sanctions.

US Department of the Treasury and state department teams have traveled to more than two dozen countries since Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal on May 8, warning companies and countries of the dangers of doing business with Iran.

US allies Japan and South Korea have already ceased importing Iran’s crude.

However, the situation is less clear among other, bigger buyers.

Brian Hook, the state department’s special representative for Iran, and Frank Fannon, the department’s top energy diplomat, met with officials in India, Iran’s No. 2 buyer, in the middle of last month after a US source said for the first time that the US administration was actively considering waivers.

An Indian government source said India told the US delegation that rising energy costs caused by a weak rupee and high oil prices meant zeroing out Iranian purchases was impossible until at least March next year.

“We have told this to the United States, as well as during Brian Hook’s visit,” the source said. “We cannot end oil imports from Iran at a time when alternatives are costly.”

A US diplomat confirmed the discussions, saying limited waivers for India and other countries were possible.

India typically imports more than 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) of Iranian oil, but has reduced that level in the past few months, according to official data.

Discussions are also under way with Turkey, Iran’s fourth-biggest crude buyer, even though Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Turkish ministers have openly criticized the sanctions.

An industry source in Turkey familiar with the talks told reporters that the country had cut Iranian imports in half already, and could get to zero, but would prefer to continue some purchases.

Obama’s administration granted a six-month waiver to Turkey, but the source said Turkey expected the Trump administration to impose tougher requirements for obtaining waivers that could potentially cover shorter periods.

“It could be for three months, or they may not get a waiver at all. It is all a bit unpredictable this time, as we understand a lot of things are up to Trump,” the source said.

The situation is least clear in China, Iran’s biggest customer, whose state-owned buyers are also seeking waivers. The country took in between 500,000 bpd and 800,000 bpd from Iran in the past several months, a typical range.

Beijing’s signals to its refiners have been mixed, the two sources said.

Last week, Reuters reported that Sinopec Group and China National Petroleum Corp, the country’s top state-owned refiners, have not placed orders for Iranian oil for this month because of concerns about the sanctions.

Joe McMonigle, energy analyst at Hedgeye in Washington, said he expected the US administration would have to accept some level of Iranian oil buying from China, given its consumption.

“Of all the countries, I don’t think they think China is going to zero,” he said.

Additional reporting by Nidhi Verma, David Gaffen and Aizhu Chen

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its