Nigeria, one of Africa’s two wealthiest economies, has overtaken India as home to the world’s greatest concentration of extreme poverty amid warnings that the continent is to host nine out of 10 of the world’s poorest people within 12 years.

The claim comes as concerns mount that the growth in poverty — and in Africa in particular — is outpacing efforts to eradicate it.

It was made in a paper for the Brookings Institution think tank by three experts associated with the World Poverty Clock, which was launched last year to track trends in poverty reduction.

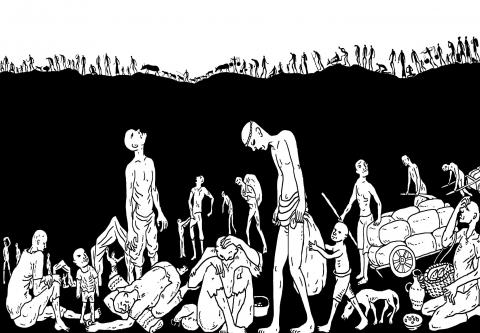

Illustration: Mountain People

Energy-rich Nigeria in May overtook India to become the nation with the world’s highest number of people — 87 million — living in extreme poverty, compared with India’s 73 million people, the authors said.

The report says 14 of the 18 nations in the world where the number of people in extreme poverty is rising are in Africa. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, ranked third, is also expected to overtake India soon.

Previously, the ambition of eradicating extreme poverty — the first of the UN’s 17 sustainable development goals, adopted by world leaders at a historic summit in September 2015 — had been lauded as a success story.

Trajectories for poverty in African nations have already been raising concerns among policymakers over issues as diverse as stability, security and migration trends, already a serious concern in Europe.

Inevitably, the claims have prompted sharp differences of opinion in Nigeria, where assessing poverty figures is a political issue.

In a hard-hitting editorial last week, the Punch daily newspaper noted the rise in poverty since 2010.

“For a country that is so richly blessed, Nigeria’s poverty narrative is an embarrassment to both the citizens and outsiders,” it said.

However, the Brookings report has not come as a surprise to keen observers of events in Nigeria after the World Bank had earlier warned of growing poverty in the nation.

“Back in February, the African Development Bank had said that 152 million Nigerians, representing almost 80 percent of the country’s estimated 193.3 million population, lived on less than US$2 per day,” it said.

However, Nigerian Minister of Trade, Industry and Investment Okechukwu Enelamah said that the figures reflected a period when Nigeria was in recession.

“I think first we need to understand there are reports that are lagging in indicators, which means people are reporting on history,” he said, adding that he hoped Nigeria’s economic policies would lead to a reduction in poverty.

The figures mark a profound change in the pervading narrative of global poverty — and where it is concentrated — throwing up challenges for the international community, the report’s authors said.

They show the number of extreme poor in India is declining at a rate of about 44 people a minute, compared with Nigeria, where it has been rising by six people a minute.

Homi Kharas, one of the Brookings authors who helped set up the World Poverty Clock, said that the clock was intended as a device to dramatize the rate of poverty reduction required to end extreme poverty by 2030.

“It gives you the speed, not the level of poverty reduction, and the world has been going happily along celebrating the fact that a lot of people are coming out of poverty,” he said. “But the fact is the speed is not only less than required, but it is not doing well, particularly in Africa.”

While population growth in India is dropping even as it enjoys economic development, in African nations, the opposite is true, Kharas said.

“Africa has the fastest-growing population of any major region, while population growth in India is probably under 1 percent,” he said. “In Africa, however, a slow combination of population growth, conflict, economic and social problems, and bad government and bad governance has led to the current situation.”

“Nigeria is a rich country, but because much of its wealth comes from the production and sale of oil, it doesn’t directly go to the pockets of ordinary people,” Kharas added.

For those struggling with poverty in Nigeria, the issues are more visceral.

Mohammed Ahmed, 33, is a Muslim teacher and father of four from Abuja. He said that once he has paid for his children’s school expenses, there is barely enough to feed the family.

“My salary is 20,000 naira [US$55.40] per month. Even though school is free, we still need to pay examination fees and other costs,” he said. “I go to the market to buy food every day. I spent about 400 to 500 naira to feed eight people every day, because I have other relatives living with me. It is very tough, but I try to feed my family twice a day.”

The shift in the center of global poverty from Asia to Africa is no surprise to Andrew Shepherd, director of the Chronic Poverty Advisory Network at the Overseas Development Institute, which noted the trend several years ago.

“Broadly speaking, I would agree that there is a shift from Asia to Africa, although it is probably slower than some people think,” Shepherd said.

The situation appears to be exacerbated in African nations by features less visible in many Asian countries, including questions of poor governance, harsher effects of climate change and conflict, he added.

“I think it is shifting to states that are conflict-affected and states most affected by climate change — and there is quite a correlation between the two — and states that have both poor policies and are significantly underfunded and in terms of aid,” he said. “There is a whole bunch of these states and a significant number are in Africa.”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its