About one in 10 British civil servants at the European Commission has taken another EU nationality since the Brexit vote, but is nonetheless resigned to scant prospects of future promotion.

Figures from EU data provided to Reuters and interviews reflect a pessimistic view of the future in Brussels for nearly 900 remaining British staff on the EU executive once Britain leaves the bloc in March next year following its June 2016 referendum.

They also highlight the role of nationality in EU career advancement, despite a formal taboo on discrimination according to passport — as some Britons have already found to their cost.

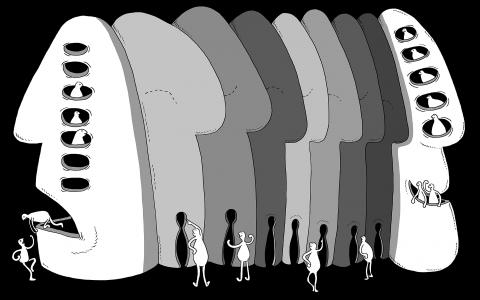

Illustration: Mountain People

“As Brits, our careers here are already finished,” said one mid-ranking official with more than 20 years service at the commission who, like many of those switching, has now acquired an Irish passport through descent.

“But no one will see me as Irish. This is basically just an insurance policy for now,” the official said.

EU President Jean-Claude Juncker in late March gave British staff a formal undertaking that the commission would not exercise its right to dismiss them after March 29 next year when they lose the EU citizenship that is a normal requirement for employment.

However, despite such sympathy at the top for their plight, Britons have already been voting with their feet.

Public data shows that on Jan. 1 there were 894 commission employees whose officially recorded first nationality was British. That was down 135, or 13 percent, from a year earlier and 240, or 21 percent, fewer than at the start of 2016.

Internal data cited by an EU official showed that since May 2016 “slightly above 150” Britons retired, resigned or left at the end of the kind of temporary contract given to a quarter of the commission’s 32,000 staff; about 65 British citizens were hired, but all but four of these were on short-term contracts.

Strikingly, compared with that net decline of 85, “slightly above 100” more Britons also switched their “first nationality” to another of the 27 EU states, notably to Ireland, where many millions of British people have roots, as well as to France.

In a tweet sent on the day after the Brexit vote devastated his colleagues, one British EU official with dual nationality posted a photograph of a bottle of Irish whiskey.

“Time to connect with my Irishness to numb my wounded Britishness,” he wrote.

Britain allows dual nationality, so those switching in the EU are not obliged to renounce their UK citizenship.

Conversations with EU officials — none would speak on the record about personal choices — showed some Britons already had dual citizenship and have merely switched the “first nationality” recorded in commission records.

Some raced to acquire new passports after the referendum. Others also have another citizenship, but have yet to formally switch to it, while many are thinking of or are applying to other countries.

Among these, notably, is Belgium. It has resisted granting citizenship to some EU officials, despite many having spent decades living in Brussels, on the grounds that they have not been in the local tax system.

Juncker this month appealed personally to the Belgian prime minister to show them compassion.

The issue of nationality in EU careers is a delicate one. Formally, officials “leave their passports at the door,” though officials also expect teams to reflect the bloc’s diversity.

“We can’t see how changing first nationality ... could result in any sort of advantage. Promotions of EU officials are based on merit only,” a commission spokeswoman said.

Even before Brexit, that view is contested by some who say privately that British colleagues have been passed over for expected promotions or removed from work that superiors feared could cause a conflict of loyalties between Brussels and London.

Some British EU staff said that has offended them, arguing that, if anything, they feel the Brexit vote has strengthened their commitment to a project people back home have abandoned.

“It’s been painful,” one veteran staffer said. “Since the referendum, I feel much less British — but the world sees me as much less European.”

Even those switching passports see little hope — certainly not in senior positions, where national governments are unlikely to lobby for what one Irish official described as “rebadged Brits.”

Like other capitals, Dublin wants jobs for its own.

The number of Commission officials recording Irish first nationality rose by 37 to 520 in the two years to January.

An Irish EU embassy spokesman said the issue of British EU officials taking Irish nationality was “complex” and that the government was “continuing to monitor matters.”

Even without Brexit, Euro-Brits have been a vanishing breed, reflecting what many of them see as long growing indifference to the EU among British voters and successive London governments.

While they once made up closer to the 13 percent of the EU population that Britain accounts for, they are today just 3 percent of the commission, albeit better represented in the senior ranks, reflecting longer EU membership than most states and more effort to see “national balance” across the top jobs.

Some British staffers speak of serving out time until their pension; others are sticking to EU ambitions, knowing that the commission does hire some non-EU nationals with special skills.

Rather than linger in roles of diminishing responsibility, some are looking to follow colleagues into the private sector.

A few are tempted to move to a London civil service that might grow thanks to Brexit; others see little welcome from a British establishment they feel has done little for them. Amid anger, grief and uncertainty, there is deal of British stiff upper lip.

“It’s not the end of the world,” one said. “No one’s going to be helicoptered off the embassy roof, Saigon-style.”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its