It was all there on paper in black and white, down to the precise number of centrifuges: The terms of a potential “fix” that US President Donald Trump had demanded for the US to stay in the Iran nuclear deal.

Dragged kicking and screaming into five months of negotiations, the US’ closest allies in Europe had finally agreed in principle to the toughest of Trump’s demands. They conceded that some expectation could be put into place in perpetuity that Iran should never get closer than one year from building a bomb. All that was left was to figure out creative language for how that constraint would be phrased that everyone could support.

Trump walked away from the deal anyway.

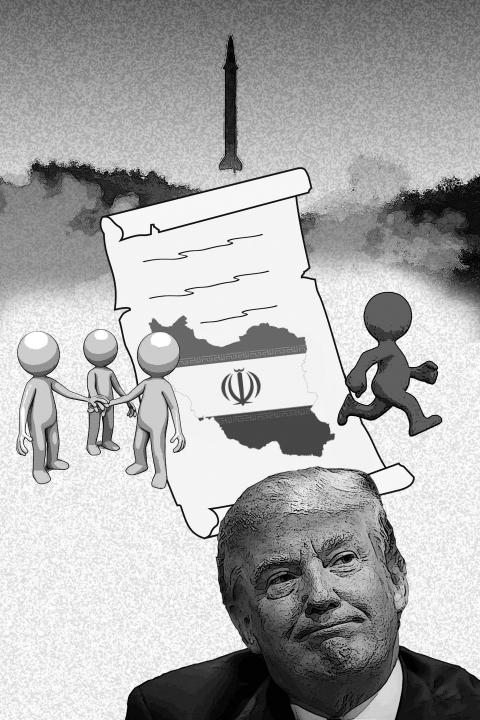

Illustration: Constance Chou

Announcing that the US was out, he called the 2015 pact his predecessor brokered “defective at its core” and said the US would immediately re-impose sanctions lifted under the deal.

“We can’t allow a deal to hurt the world,” Trump added on Wednesday, as the world scrambled to figure out what comes next.

However, behind the scenes, the Trump administration had been actively preparing for a pullout since January, when Trump declared that he would withdraw if an “add-on” deal was not reached. To many US officials, it was as clear then as now that Trump would not be swayed to accept even a toughened-up version of the accord.

This account of how Trump withdrew from the deal draws on interviews on Wednesday with a dozen US White House officials, senior US Department of State officials, foreign diplomats and outside advisers to the Trump administration involved in the negotiations. Most were not authorized to comment publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

Trump had just celebrated the anniversary of becoming president in January when he issued his ultimatum: If there was no fix to the deal by yesterday, the US would be out. There was no chance that three of the deal’s members — Iran, Russia and China — would consider changes, so Trump focused on the Europeans — Germany, the UK and France — in hopes that the rest would go along once a fix was agreed to by the rest.

“This is a last chance,” Trump said.

Right away, a team led by Brian Hook, the State Department’s policy chief, began intensive negotiations with the Europeans on the issues that Trump insisted had to be fixed: new penalties on Iran’s ballistic missile inspections, expanded access for UN nuclear inspectors and an extension of the restrictions on Iran’s enrichment beyond the current life of the deal.

Before long, the US found the Europeans were amenable to dealing with the first two. The third was a non-starter. After all, the terms of the 2015 deal explicitly say that the restrictions “sunset” over time. Any extension without Iran’s explicit consent would put the Europeans themselves in breach of the deal.

A supplemental agreement was drafted and tweaked, and tweaked again, even as negotiations continued about what mechanism to use to hold the Iranians to the restrictions indefinitely. At least one draft included footnotes specifying that the same nuclear parameters in the 2015 deal should continue to be in place: no more than 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges, no uranium stockpiles larger than 300kg, no enrichment beyond 3.67 percent and no advanced centrifuges, according to an individual who read the draft.

US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley led a parallel effort to get France and the UK to toughen up on other Iranian behavior, such as its support for Hezbollah militants in Lebanon and for Shiite Muslim Houthi rebels in Yemen. Haley’s argument to the Europeans: Helping us with these side issues can only help you make your case to Trump to stay in the deal.

However, at the White House, senior staffers were skeptical that anything would satisfy Trump. After all, Trump had already told aides that he refused to waive sanctions on Iran again. So White House and US National Security Council staff began laying the groundwork for a US withdrawal, even as the negotiations with the Europeans were underway.

As the deadline drew closer, the Europeans grew increasingly alarmed that Trump seemed determined to scrap the deal, and so began a parade of visits by their leaders to the White House to make the case in person.

First came French President Emmanuel Macron, the European leader closest to Trump. Not only did he raise the issue during a state visit, but he also took the extraordinary step of hammering the point in a speech to a joint session of the US Congress.

“We signed it, both the United States and France,” Macron said of the pact. “That is why we cannot say we should get rid of it like that.”

The Germans followed days later, with Chancellor Angela Merkel emphasizing Europe’s openness to working with Trump to crack down more comprehensively on Iran.

The closing pitch was left to British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Boris Johnson, who even appeared on Trump-friendly Fox & Friends to urge him not to walk away.

Johnson and the others came to Washington armed with clever solutions to the remaining hang-up over extending restrictions on Iran permanently. The Europeans were firm on one point: They could not unilaterally impose on Iran what it had not agreed to in the deal.

However, there were ideas to use other mechanisms that could not expire, such as supervision of Iran’s civil nuclear needs, to ensure it stayed within the bounds and did not approach a bomb.

By the time that Johnson arrived, it had become clear that the negotiations, while still ongoing, were futile.

Trump on Monday tweeted that he would announce his decision at 2pm on Tuesday — almost a week before his deadline.

His decision was kept closely quarantined until the end, with even most White House, State Department and US Department of the Treasury officials unsure what he had decided. The State Department and Treasury prepared three versions of the public statements and technical guidance that would have to be released with his decision: one for staying in, one for full withdrawal and one midway option in which only some sanctions would be immediately re-imposed, potentially preserving the possibility that the US could later reverse course and stay in.

Trump’s administration also did not explicitly tell the Europeans that he was withdrawing. In a call with Macron just ahead of his announcement, Trump made clear he was still ardently opposed to the deal, but left Macron guessing about precisely what he would do.

He and the other Europeans learned when everyone else did: on Tuesday, when Trump appeared on live television in the Diplomatic Reception Room and said that he was out.

“The fact is this was a horrible, one-sided deal that should have never, ever been made,” Trump said. “It didn’t bring calm, it didn’t bring peace, and it never will.”

Additional reporting by Jill Colvin

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its