Mostafa al-Asar’s lawyer said he had barely started work on a documentary critical of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi when police arrested him and charged him with publishing “fake news.”

The journalist was detained before he had even begun filming, his lawyer said.

The government did not respond to requests for comment.

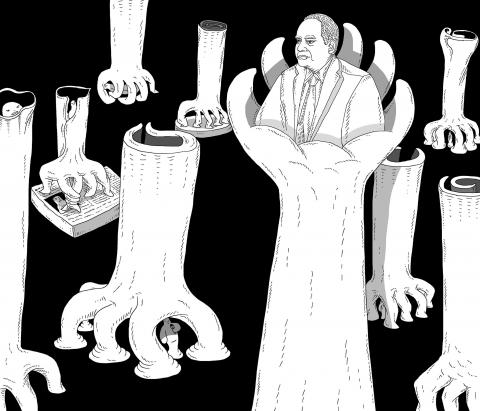

Illustration: Mountain People

The arrest on Feb. 4 came ahead of a presidential election, which is to be held from Monday to Wednesday next week. Al-Sisi is virtually guaranteed to win. All opposition candidates except one have dropped out citing intimidation, while the remaining challenger has said he supports the president.

The election commission says it has been receptive to any complaints and the vote would be fair and transparent.

As the election nears, Egypt has turned its attention to news outlets and journalists it accuses of spreading lies, including some foreign media and even one pro-government commentator.

Authorities say curbing fictitious news is necessary for national security. They regularly accuse outlets of a lack of professionalism in covering Egypt and urge reporters to use only official outlets as sources.

Egyptian prosecutors have long urged that critical outlets be silenced. Authorities have now gone further, with the public prosecutor calling for legal action over what he deems fake news, saying the “forces of evil” are undermining the Egyptian state.

Makram Mohammed Ahmed, head of Egypt’s Supreme Media Council, a state media regulator, voiced concerns about media standards.

“I no longer believe that there’s an independent press, or that there’s professionalism... There is a lack of accuracy, whether in Egyptian papers or the foreign press,” he said.

Rights groups such as the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) and the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms say the charge of publishing false news aims to rein in dissent, targeting journalists, politicians and even pop stars.

The public prosecutor this week announced telephone hotlines for citizens to report “news relying on lies and rumors.”

Al-Sisi weighed in on March 1, saying that anyone who insults the army or police — and by extension himself as commander in chief — is guilty of treason.His words prompted lawmakers to consider new legislation that would jail such offenders for up to three years, according to pro-government media.

The debate over media standards heated up last month when the BBC released a report on human rights detailing the alleged forced disappearance of an Egyptian woman, who later appeared on a pro-government talk show to refute the claim.

Egypt’s government press center said the BBC report was “flagrantly fraught with lies” and urged officials to boycott the British public broadcaster.

The BBC said it “stands by the integrity” of its reporting teams. A Cairo court has said it will next month hear a case filed by a lawyer over the report, calling for the closure of the BBC’s Cairo office.

Egypt’s campaign against the media has included state television presenter Khairy Ramadan, whose brief detention prompted alarmed comments by pro-government talk show hosts who rarely speak out against authorities.

“Khairy Ramadan [and other Egyptian journalists] are not our enemy — he’s a national broadcaster,” TV host Amr Adib said on his nightly show.

Ramadan, who was questioned for defaming the police after a segment on an officer’s family struggling to get by financially, was released on bail on March 5. Neither Ramadan nor his lawyer could be reached for comment.

Lower-profile reporters have also been held.

According to his lawyer, al-Asar was setting up interviews for a film about al-Sisi supporters turned dissidents when he was arrested on his way to work.

“[Al-Asar] was talking to a guest to coordinate an interview and the call was recorded and monitored,” his lawyer Halim Hanish said.

Another journalist, Hassan al-Banna, was arrested with him as they rode in a bus together “simply because he happened to be with [al-Asar],” Hanish said.

The Egyptian Ministry of Interior and government press center did not respond to phone calls or WhatsApp messages asking for comment on the allegations of phone tapping and the arrests of journalists.

The two could face jail after being charged with publishing false news and joining an outlawed organization, typically a reference to Muslim brotherhood Fatma Serag, an AFTE lawyer who works with journalists said.

Figures from the Cairo-based AFTE show that at least six journalists have been arrested in Egypt during the first two months of this year, and that 18 were arrested last year.

“The state is now using [the fake news charge] to harass journalists — anyone that publishes information they don’t want,” Serag said.

Egypt has also blocked hundreds of Web sites during the past few months in increased censorship of online media, AFTE said.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein on March 7 criticized Egypt’s crackdown on political and press freedom, describing a “pervasive climate of intimidation” ahead of the election.

The UN report said more than 400 media and non-governmental organization Web sites had been blocked.

Egypt’s foreign ministry dismissed the comments as “baseless allegations.”

In 2015, al-Sisi pardoned three al-Jazeera television journalists who had been jailed for three years for operating without a press license and broadcasting material harmful to Egypt. The state news agency said the pardons, which included about 100 prisoners held for other offenses, were part of an initiative by al-Sisi to release a number of young people.

A few weeks ago in Kaohsiung, tech mogul turned political pundit Robert Tsao (曹興誠) joined Western Washington University professor Chen Shih-fen (陳時奮) for a public forum in support of Taiwan’s recall campaign. Kaohsiung, already the most Taiwanese independence-minded city in Taiwan, was not in need of a recall. So Chen took a different approach: He made the case that unification with China would be too expensive to work. The argument was unusual. Most of the time, we hear that Taiwan should remain free out of respect for democracy and self-determination, but cost? That is not part of the usual script, and

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed