For two months now, as accusations of sexual misconduct have piled up against Harvey Weinstein, the disgraced mogul has responded over and over again: “Any allegations of nonconsensual sex are unequivocally denied.”

Consent is a concept central to law on sexual assault and will likely be an issue in potential legal cases against Weinstein, who is under investigation by police in four cities, and others accused in the current so-called “reckoning.”

However, the definition of consent — namely, how it is expressed — is a matter of intense debate: Is it a definite “yes,” or the mere absence of “no”? Can it be revoked? Do power dynamics come into play? Legally, the definition varies widely across the US.

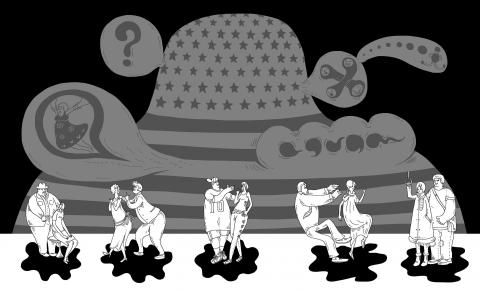

Illustration: Mountain people

“Half the states don’t even have a definition of consent,” says Erin Murphy, a professor at New York University School of Law who is involved in a project to rewrite a model penal code on sex assault. “One person’s idea of consent is that no one is screaming or crying. Another person’s idea of consent is someone saying: ‘Yes, I want to do this.’ And in between, of course, is an enormous spectrum of behavior, both verbal and nonverbal, that people engage in to communicate desire or lack of desire.”

“It’s pretty telling that the critical thing most people look to understand the nature of a sexual encounter — this idea of consent — is one that we don’t even have a consensus definition of in our society,” Murphy added.

Many victim advocates argue that a power imbalance plays a role. In nearly every instance, the allegations in recent weeks came from accusers who were in far less powerful positions than those they accused — as in, for example, the rape allegations that have surfaced against music mogul Russell Simmons, which he denies.

“You have to look at the power dynamics, the coercion, the manipulation,” said Jeanie Kurka Reimer, a long-time advocate in the area of sexual assault. “The threatening and grooming that perpetrators use to create confusion and compliance and fear in the minds of the victims. Just going along with something does not mean consent.”

Many Weinstein accusers have spoken about that uneven dynamic. For years Weinstein was one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, and most of his alleged victims were women in their 20s, looking for their first big break.

A number have indicated that his power — and fear of his retribution, both professional and physical — blunted their ability to resist his advances.

Actress Paz de la Huerta, who has accused Weinstein of rape, said in a TV interview: “I just froze in fear. I guess that would be considered rape, because I didn’t want to do it.”

One woman who did manage to escape Weinstein’s advances in a 2014 hotel room encounter addressed the power imbalance in a recent essay.

The very word “consent,” actress and writer Brit Marling wrote in the Atlantic, “cannot fully capture the complexity of the encounter. Because consent is a function of power. You have to have a modicum of power to give it.”

The anti-sexual violence organization RAINN tracks the various state definitions of consent.

The differences make for a situation that is “confusing as hell,” the group’s vice president of public policy Rebecca O’Connor said.

For many years, “we had this he said-she said mentality, where you went into court and if you couldn’t prove that you didn’t consent, the activity was deemed consensual,” O’Connor said.

Also, most US states required that the accuser show force was used, to show lack of consent.

“Of course, our thinking and understanding of these cases has evolved tremendously, and so states have acted in response to that,” she said. “What we’re finding is especially at moments like this — when it’s impossible to ignore the conversation — they are ... re-evaluating the factors that play into the definition of consent and how it can be expressed.”

For example, O’Connor said, North Carolina is looking at its law that does not allow consent to be revoked once it has been given — which means that if an encounter turns violent, as in a recent reported case, the accused cannot be charged with rape because the woman consented at the beginning.

And several US states have passed laws requiring affirmative consent — going further than the usual “no means no” standard to require an actual “yes,” though not necessarily verbal. Among those states: Wisconsin, California and Florida. In Florida, consent is defined as “intelligent, knowing, and voluntary consent and does not include coerced submission.”

“We’re not there yet, but a lot of states are starting to move the wheels on this,” O’Connor said.

The varying definitions of consent can lead to confusion among the people who most need to understand them.

Reimer recalled a Wisconsin case in which a woman had experienced a violent sexual experience with a boyfriend she was trying to break up with. She had consented to sex at other times in their relationship, but was no longer interested. This time, she said no at first, but then stopped resisting as he became more agitated and her children slept nearby.

“She thought she had consented, because she had consented before,” Reimer said. “I told her that just because you consent once, it’s not a blanket consent. Then she got it — that this time it was rape — and she got angry.”

Murphy said that when the American Law Institute began a project several years ago to rewrite sex assault laws in its 1962 Model Penal Code, consent was the first thing it tried to define.

The institute — an elite body of judges, lawyers and academics — issues model laws that are often adopted by US state legislatures. The project is aimed at updating the laws and dropping some particularly outdated notions, like the idea that rape cannot occur within a marriage.

“It’s been a laborious process,” Murphy said.

It took about five years to achieve the current consent definition, which recognizes that the essence of consent is willingness — but that how willingness is expressed depends on context.

Murphy said it remains to be seen whether the huge attention now being paid to sexual misconduct will accelerate the process of rewriting laws, or — as in the recent roiling debate over college campuses — make it more complicated.

O’Connor said she is hopeful that US state lawmakers will pick up the pace of updating their laws with new understandings of concepts like consent.

“We’ll see how all this plays out, because when you train the national spotlight on it, suddenly action is born,” O’Connor said.

Most important is for people to recognize that a lack of consent can be expressed in many different ways, she said.

“Yes, there is a legal definition for each state,” she said. “But at the end of the day a survivor knows whether or not they consented. I want the message to go out that the criminal activity of another is never a victim’s fault, and that extends to the issue of consent.”

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its