The use of armed soldiers to patrol alongside pavement cafes and selfie-snapping tourists in European cities since extremist attacks risks compromising deployments overseas, military leaders say.

Belgium and major military power France, both active in EU and NATO missions, have cut back training to free up troops, and NATO planners fear that over time armies might get better at guarding railway stations and airports than fighting wars.

Some of the more than 15,000 soldiers serving at home in Europe say tramping the streets is a far cry from the foreign adventures they signed up for and that they feel powerless to defend against militants.

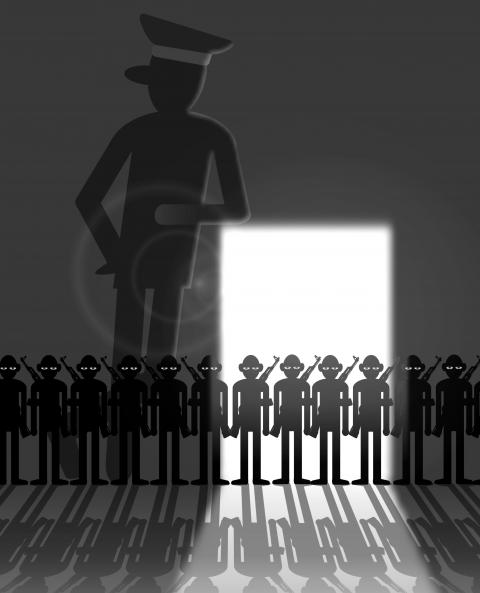

Illustration: Yusha

“We are standing around like flower pots, just waiting to be smashed,” said an officer just returned from Afghanistan for guard duty in Belgium, which, like France, has more troops deployed at home than in any single mission abroad.

Security personnel have been targeted in both countries, but patrols begun as a temporary measure after Islamic State group attacks in 2015 have become permanent fixtures as opinion polls show that people are reassured by soldiers on show at home.

Italy has had soldiers on the streets since 2008. Britain used them briefly this year and, along with Spain, is prepared for deployments if threat levels rise. Despite their painful history, Germany and Austria have debated having military patrols at home for the first time since World War II.

Across Europe, political debate is shifting from whether, to how to adapt the armed forces to a homeland role, a concern for military leaders eyeing budgets, morale and training.

France’s former military chief, who quit in July, said it had overstretched the army, while the head of Belgium’s land forces said the domestic deployment was taking its toll.

“I see a lot of people who leave our defense forces because of the operation,” General Marc Thys, the commander of Belgium’s land forces, said in an interview, without giving numbers.

Not everyone agrees.

An Italian Ministry of Defense source said its domestic patrols had “absolutely no impact on overseas missions or on training.”

However, some in NATO worry protracted domestic operations will make key members of the 29-strong transatlantic alliance less ready to deploy to Afghanistan or eastern European borders with Russia.

“It is popular with the public. It is cheaper than the police,” a senior NATO source said. “But if the requirement came to send a lot of forces to reinforce our eastern allies ... would the government be willing to pull its soldiers off the street to do that, could it?”

‘WORSE THAN AFGHANISTAN’

The challenge of battling the Islamic State at home and abroad squeezes resources just as NATO leaders seek to show US President Donald Trump that they are reliable allies, after he repeatedly questioned the alliance’s worth.

Given the homeland operations, some military sources and experts say politicians face a tough choice: to expand the army, summon up reserves or create a new domestic security force — a halfway between the police and military — to replace them as Belgium has chosen to do over the coming years.

“It mobilizes so many people that we are having trouble deploying people abroad for UN and EU missions,” a second NATO source said.

The operations put 10,000 heavily armed combat troops on the streets in France and 1,800 in Belgium after the Islamic State attacks in early 2015. The numbers are down to 7,000 and 1,200 respectively, but they still tie up about one-10th of the deployable army personnel in each nation.

They can also be bad for morale.

The mix of schools, offices and warehouse hastily converted into barracks in Belgium “are worse than Afghanistan,” a soldier said, showing pictures of cramped rooms piled high with gear.

About 45 percent of soldiers surveyed by the Belgian military in December last year said they were thinking of quitting — many to the police — as being away had strained families and led to divorce.

A source in the French military, which has not made polling public, said of its street patrols, known as Operation Sentinelle: “Sentinelle is a burden whose impact on soldiers’ morale we’ve never denied.”

For now, Thys said the Belgian armed forces are not pulling back from foreign missions, but have less time for training.

“We take everything into account, our homeland operation and our international missions. If you go up on one side, we have to go down on the other side,” Thys said.

In France, training days last year were cut from 90 to 59 days, according to a French Ministry of Defense report in October last year.

A decline of about 30 percent began with the deployment on home soil, experts say.

“The longer they do it, the less sharp as a military they are,” said General Richard Barrons, Britain’s former military chief. “But once you are committed to this it takes a very brave politician to turn it off.”

The new head of France’s armed forces, which has thousands of troops abroad fighting Muslim militants in the Sahel, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere, said something has to give.

“We have to choose how to adjust our commitments, to give us back some flexibility, because who knows where the French army will have to deploy in a year,” French General Francois Lecointre was cited by local media as saying earlier this month.

French President Emmanuel Macron has announced a strategic review of the street patrols.

French Minister for the Armed Forces Florence Parly on Tuesday said the patrols would not be cut, but would be made more flexible.

TARGET OR DETERRENT?

In Italy, where up to 7,000 soldiers assist police, a defense ministry source said they were moved around often to keep them from becoming bored — an approach that both France and Belgium are now planning to implement.

Italy has escaped militant attacks so far and troops elsewhere have disarmed or killed would-be attackers — such as a knife-wielding assailant outside the Eiffel tower last month and a suitcase bomber in Brussels in June.

However, their effectiveness is hard to quantify, and attacks on men in uniform like that in Paris last month — with its familiar pattern of a car ploughing into its victims — has renewed fears that they might draw fire or shoot in error.

In France, three in four voters approve of street patrols, although nearly 40 percent doubt they are effective in combating terrorism.

In Belgium, support for the military is 80 percent, up from 20 percent before the mission.

“It’s a PR operation, nothing more,” said Wally Struys, a professor emeritus at Belgium Royal Military Academy.

However, Thys and others see no end to the operations, which give the military an extra argument against years of declining budgets.

“They are part of the landscape now,” said Saad Amrani, chief commissioner and policy adviser of the Belgian Federal Police. “We depend on them.”

Additional reporting by Sophie Louet and Laurence Frost in Paris, Antonella Cinelli in Rome and Alba Asenjo Dominguez in Madrid.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its