Once again, well-informed people, including British politicians, have been surprised by an election result because they put too much trust in traditional polls. It is time to get smarter about assessing voter preferences. The tools are there for those who want them.

On the eve of Thursday’s election, British newspapers and many outside observers expected a landslide victory for the Conservative Party. Even a 100-seat majority in the 650-seat parliament was still being discussed. That is because both polls and prediction markets signaled such an outcome.

The Financial Times’ polling average showed that British Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservatives would win 44 percent of the vote to 36 percent for Jeremy Corbyn’s opposition Labour Party. On Wednesday, Betfair had the Conservatives at odds of 2-to-9 to win a majority and no majority at 5-to-1. On the surface, there was every reason to expect success for May’s plan to get a strong mandate for her party.

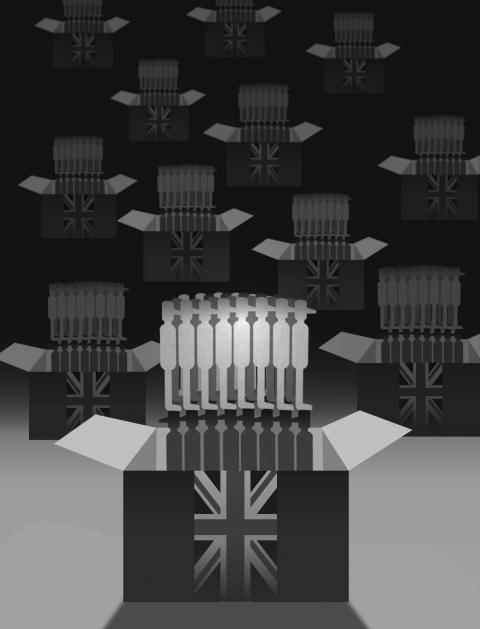

Illustration: Yusha

That is unless you followed the YouGov election model developed by Benjamin Lauderdale of the London School of Economics (LSE). An outlier compared to traditional polls, it consistently predicted the actual outcome — a hung parliament, in which no party would have a majority.

The model is a hybrid of an opinion survey and big-data exercise. It uses a small number of responses to survey questions to figure out how voting is related to individual characteristics of people living in each constituency, and then projects the result based on that constituency’s demographic breakdown and past voting record.

This approach — the scientific name is multi-level regression and post-stratification — is a relatively cheap way of matching the survey methodology to the UK’s electoral system, in which politicians contest individual constituencies. The big data part of the model allows pollsters to avoid the cost of surveying large samples in each constituency.

Most of the other UK polls assessed the national vote breakdown — the share of the vote each of the parties was expected to get — by using nationwide samples. They would have been relevant — assuming the samples were representative — in, say, a Dutch parliamentary election, where parties compete in a single nationwide constituency.

National polling can also work in Germany, where every citizen gets two votes — one for a specific candidate in an electoral district and one in a Dutch-style nationwide proportional system; the two votes are usually well correlated. It can also work in a French presidential election, where the nation is a single constituency, too. That is why respectable Dutch, French and German polls using nationwide samples are worth following.

In the US, where the successful presidential candidate needs to win the most electoral votes, outcomes in individual states matter more than the results of the nationwide popular vote. Just as polls based on national samples predicted, failed Democratic US presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton won the popular vote last year.

The controversial University of Southern California and Los Angeles Times poll, which used a sample weighted differently from most others, predicted then-Repulican US presidential candidate Donald Trump would win — but it was wrong, too. Yet Trump won the presidency.

The US needs more complex models than these nationwide polls so it can better gauge local voting patterns. However, these are rare so far. The polling firm Morning Consult applied a YouGov-style approach in April last year and found that Clinton was the strongest candidate at that time.

However, closer to the election, media outlets only cited traditional polls from the firm. YouGov ran a version of Lauderdale’s model in the US, too, and it predicted a Clinton victory. So far, the YouGov model has proved itself better in the UK, where it also predicted the Brexit vote, than in the US. However, it is a work in progress and it can be better calibrated by the next US election.

Italy, too, needs a similar model for its next election, which is increasingly likely to take place this year. The major parties recently tried to strike a deal to change the electoral system to a German-style one. That would have made traditional nationwide samples relevant, but the deal now appears to be off. This means an early election might be held according to the convoluted 2015 system, known as “Italicum.”

It divides the country into 100 constituencies, electing from three to nine candidates each, based on separate party lists for each constituency. Candidates can run in multiple constituencies at once. There is a bonus for a party that can get more than 40 percent of the vote: It is automatically rewarded with a majority.

The potential early election worries investors because of the anti-EU, populist Five Star Movement’s current lead in the polls. However, these polls do not reflect the system. They are potentially as unreliable as British polls turned out to be.

Similarly, the UK election has confirmed that following bookmakers’ odds has a major limitation. People with the most money tend to bet according to poll results, skewing the odds heavily toward the outcome they predict. However, smaller bettors — the ones who are more likely to feel the mood in their constituencies because they go to the right pubs — ignore the polls.

According to Betfair, “no outright majority” attracted a greater number of bets before the UK election than “Conservative majority.” If one wants to follow the prediction markets intelligently, it makes sense to pay attention to the number of bets as well as to the posted odds. Bookmakers are only concerned with making a profit, so the amount of money riding on a certain outcome determines the odds they make. For watchers who do not bet, a hybrid approach is more rational.

As someone who constantly has to monitor polls in multiple elections, I am by now convinced of the value of multiple-input analysis. I am on the lookout for models that combine polling and big data, I ask bookmakers for more information than the odds they post and I watch how candidates do on the social networks and on Google. In the UK election, the Labour Party had a 45 percent search share, compared with the Conservatives’ 21 percent. To me, that suggested that polls could be overestimating May’s chances.

However, most importantly I find that voting intention studies must closely match a nation’s electoral system. The better they are aligned, the more logical it is to use them as vote result predictors. If a country’s electoral system is complex and highly localized, traditional polls will be off.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion Web site Slon.ru.

As strategic tensions escalate across the vast Indo-Pacific region, Taiwan has emerged as more than a potential flashpoint. It is the fulcrum upon which the credibility of the evolving American-led strategy of integrated deterrence now rests. How the US and regional powers like Japan respond to Taiwan’s defense, and how credible the deterrent against Chinese aggression proves to be, will profoundly shape the Indo-Pacific security architecture for years to come. A successful defense of Taiwan through strengthened deterrence in the Indo-Pacific would enhance the credibility of the US-led alliance system and underpin America’s global preeminence, while a failure of integrated deterrence would

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

Taiwan is confronting escalating threats from its behemoth neighbor. Last month, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted live-fire drills in the East China Sea, practicing blockades and precision strikes on simulated targets, while its escalating cyberattacks targeting government, financial and telecommunication systems threaten to disrupt Taiwan’s digital infrastructure. The mounting geopolitical pressure underscores Taiwan’s need to strengthen its defense capabilities to deter possible aggression and improve civilian preparedness. The consequences of inadequate preparation have been made all too clear by the tragic situation in Ukraine. Taiwan can build on its successful COVID-19 response, marked by effective planning and execution, to enhance

Since taking office, US President Donald Trump has upheld the core goals of “making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous,” fully implementing an “America first” policy. Countries have responded cautiously to the fresh style and rapid pace of the new Trump administration. The US has prioritized reindustrialization, building a stronger US role in the Indo-Pacific, and countering China’s malicious influence. This has created a high degree of alignment between the interests of Taiwan and the US in security, economics, technology and other spheres. Taiwan must properly understand the Trump administration’s intentions and coordinate, connect and correspond with US strategic goals.