When “Flappy McFlapperson” and “Skybomb Bolt” sprang into the sky for their annual migration from wetlands near Beijing, nobody was sure where the two cuckoos were going. They and three other cuckoos had been tagged with sensors to follow them from northern China.

The question is, to where?

“These birds are not known to be great fliers,” said Terry Townshend, a British amateur birdwatcher living in the Chinese capital who helped organize the Beijing Cuckoo Project to track the birds.

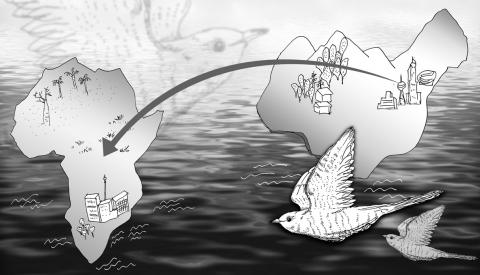

Illustration: Tania Chou

“Migration is incredibly perilous for birds and many perish on these journeys,” Townshend said.

The answer to the mystery — unfolding in passages recorded by satellite for more than five months — has been a humbling revelation even to many experts. The birds’ journeys have so far covered thousands of kilometers, across a total of a dozen countries and an ocean.

The “common cuckoo,” as the species is called, turns out to be capable of exhilarating odysseys.

“It’s impossible not to feel an emotional response,” said Chris Hewson, an ecologist with the British Trust for Ornithology in Thetford, England, who has helped run the tracking project. “There’s something special about feeling connected to one small bird flying across the ocean or desert.”

However, to follow a cuckoo, you must first seduce it.

The common cuckoo is by reputation a cynical freeloader.

Mothers outsource parenting by laying their eggs in the nests of smaller birds, and the birds live on grubs, caterpillars and similar soft morsels.

British and Chinese bird groups decided to study two cuckoo subspecies found near Beijing, because their winter getaways were a puzzle. In an online poll for the project, about half the respondents guessed they went somewhere in Southeast Asia.

“We really didn’t know for sure,” said Yu Fang (于方), a coffee importer, a prominent member of the Beijing birdwatching community and a volunteer on the project.

“We knew that the cuckoos breed around here, but where do they go over winter? I guessed it was India,” Yu said. “I’ve been birdwatching in India, and they are often spotted there. I thought that’s where they stopped.”

To tag the birds, the team set up soft, barely visible nets in May to safely catch them. A stuffed female cuckoo was attached to a tree or bush and a recording of the bird’s come-hither mating call was played out.

They responded lustily.

“The male cuckoos just can’t resist. They come in from a long way,” said Townshend, who works as a consultant on a variety of environmental projects.

Unexpectedly, female cuckoos also came to the party, seemingly jealous about an apparent rival in their patch, he said.

After excluding birds too light to safely carry the sensors, the team attached solar-powered tags weighing 4.5g to the backs of five birds, each weighing about 100g, and freed them into the wild, where satellites followed the signals from their tags. Such technology has revolutionized the study of migratory birds since the 1990s.

“Tracking technology has ushered in a new age of exploration,” Hewson said.

However, the project was also intended to raise awareness of wild birds and their needs, especially in China, where expanding cities, pollution and commercial capture with huge nets threaten the creatures. Schools in Beijing for local and foreign children gave the birds their names.

Aside from Skybomb and Flappy, there were Hope, Zigui (子規) and Meng Zhi Juan (夢之娟), a poetic Chinese phrase meaning “dream bird.”

The wait began. As blazing summer arrived, time approached for the birds to begin their migration. However, not all could. Cuckoos often have brief lives. The trackers ran out of contact with Hope after she flew north to Russia, possibly dying or losing her tag. And Zigui’s signal stopped near Beijing, where he probably perished.

Then in early August, Flappy struck south, followed weeks later by Skybomb and then Meng Zhi Juan. Each day, Townshend checked the satellite data to see whether any other birds were on the move. Their journeys, chronicled on Twitter, drew in more and more fans.

By mid-September, Skybomb and Flappy were in India. That more or less ruled out the idea that they were headed to Southeast Asia and they appeared likely to head west. However, by which route?

The first answer came in late last month. Skybomb struck out boldly from central India and, without stopping, headed across the northern Indian Ocean, apparently aiming to reach Africa in one lunge. It was a breathtaking gamble for one of these small birds.

“When Skybomb set out across the ocean, it was like: ‘Whoa. He’s going for it,’” Townshend said.

Skybomb had fattened on grubs, but Africa was thousands of kilometers away without the prospect of a stop or meal in between.

“It was a real celebratory moment, but fingers were crossed that he was going to make it across the ocean,” Townshend said.

There was an implacable logic in the cuckoos’ seeming folly, said Hewson, who had guessed that they would go to Africa.

They stopped over in India when rains had still left plenty of food there and waited for the monsoon winds to make a drastic turnaround, so the birds could fly onward with the help of the breeze. Cuckoos that summer in Europe also head to Africa to avoid the winter.

Skybomb plowed on. Flying at about 793m above the sea, he held to an astonishingly straight path, apparently calibrating for shifts in the wind and conditions. By the second day, he was halfway across. After a third day, the east coast of Africa, and food and rest, beckoned.

For much of the flight, Skybomb was helped by tail winds. However, as land approached, crosswinds and then a front-on headwind struck. It was a moderate breeze, but maybe enough to exhaust a cuckoo after days without stopping.

On Oct. 31, Townshend announced on Twitter that Skybomb “is in Africa.”

Sixty-four days after he had begun his migration, the cuckoo had reached the coast of Somalia about an hour after dusk. He had flown non-stop for 3,700km from central India.

“What a bird,” Townshend declared.

However, even then, Skybomb was not done. Right away, he flew for another 305km until he reached an area where recent rains would have brought a proliferation of caterpillars and grubs to eat. Somehow, he knew where to follow the rain.

The other birds began their long flights later than Skybomb. Flappy took a more cautious path, crossing the Arabian Sea from India to Oman. That made for a shorter flight over water, but also meant she hit land in northern Africa, farther from the lusher terrain to the south.

By Friday last week, Meng Zhi Juan had jumped to just a few kilometers from the Indian coast and appeared poised to follow Skybomb’s swoop across the ocean to Somalia or thereabouts.

The birds appear likely to edge south in Africa, following the rains. If they survive, they are expected to arrive back in Beijing in May.

Townshend and his colleagues hope to follow more cuckoos next year, if they attract enough donations to pay for the tags and satellite services. More knowledge will help protect the areas where the birds need to stop.

“They’re birds that are shared by China, India, Myanmar, Somalia and wherever else they go,” Townshend said. “With that comes a shared responsibility to protect them.”

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

When a recall campaign targeting the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators was launched, something rather disturbing happened. According to reports, Hualien County Government officials visited several people to verify their signatures. Local authorities allegedly used routine or harmless reasons as an excuse to enter people’s house for investigation. The KMT launched its own recall campaigns, targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers, and began to collect signatures. It has been found that some of the KMT-headed counties and cities have allegedly been mobilizing municipal machinery. In Keelung, the director of the Department of Civil Affairs used the household registration system