Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has started talking about Turkey’s borders, hinting they should be shifted outward a bit. In Syria and Iraq, his army is involved in wars over territory once ruled from Istanbul. Maps of a “greater Turkey” have circulated.

That has led to speculation that Erdogan, fresh from surviving an attempted coup, wants to crown his 14-year rule in Turkey by annexing chunks of its neighbors.

However, analysts see a more mundane domestic calculation behind the rhetoric: They say the president is really trying to expand his own powers, not his country’s frontiers.

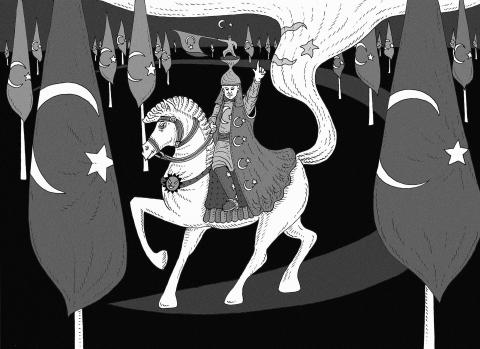

Illustration: Mountain People

Erdogan still hankers after making his office the focus of all power in Turkey, instead of the largely ceremonial post it was before he took over — and, on paper, still is.

However, he does not have support in Turkish parliament to make that constitutional change — and maybe not in the country, either, if it went to a referendum. In both cases, the likeliest bloc of voters to be won over are nationalists who are not at all averse to talk of Turkey’s historic claims to nearby lands, or military attacks on Kurdish groups who live there.

“Erdogan is seeking to expand his support base among nationalists by talking tough over regional matters,” said Nihat Ali Ozcan, an analyst at the Economic Policy Research Foundation in Ankara.

It is “part of his political calculations for a presidential system,” Ozcan said.

Last week’s domestic crackdown on Kurdish politicians, which triggered sharp falls on financial markets, might be part of the same calculus. Likewise, Erdogan’s recent support for reinstating the death penalty, which could be applied to Kurdish militants as well as members of the Muslim secret society said to be behind the failed putsch in July. That idea won backing from the Nationalist Movement Party, whose lawmakers would be swing voters when plans for constitutional change reach parliament.

Requests for comment for this story to the Turkish presidency’s press office went unanswered. Ilnur Cevik, a chief adviser to Erdogan, also did not respond to calls seeking comment.

Erdogan’s foreign policy has become more assertive since the coup attempt. In August, he sent troops into Syria, where they are pursuing the Islamic State group (IS), but also clashing with fighters linked to the separatist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) — the group that is a main target of Erdogan’s crackdown at home. Its Syrian affiliates have established control over much of that country’s north during five years of civil war, and in doing so, emerged as a favored US fighting force in the ground war against IS.

OTTOMAN TERRITORIES

In recent days, Turkey has been sending tanks and troops to its Iraqi border too, ready to bolster a 2,000-strong force that is already inside the country — despite loud protests from Baghdad.

Erdogan insists that Turkey will join in the ongoing liberation of Mosul, the biggest Iraqi city in the IS’ self-proclaimed caliphate. Justifying that stance, which has dismayed many allies, he has repeatedly referred to Turkey’s past rule over the region.

Pro-government media dug up the history of oil-rich Mosul and Kirkuk, provinces of the Ottoman Empire that almost became part of the Turkish Republic created after World War I. Instead they went to another new state, Iraq, which was then under a British mandate and Turkey formally dropped its claim over them in the late 1920s.

‘COLLECTIVE MEMORY’

Still, “Mosul maintains a position of unique historical relevance in Turkey’s collective memory,” the Soufan Group, a security analyst, said in an e-mailed report.

It said Erdogan’s deployment of troops nearby is part of “Turkey’s effort to strategically position itself and the forces it supports to prevail in the aftermath of the battle.”

As in Syria, the IS is not Turkey’s only enemy in Iraq and not necessarily the most important one. Erdogan has called Sinjar, west of Mosul, a “sensitive target” for Turkey. Over the past year, it has become a base for PKK fighters who helped drive the extremists out of the town.

To be sure, Erdogan has other reasons besides domestic politics to seek influence over the conflicts convulsing Turkey’s neighbors.

‘FAILED STATES’

“Turkey sees that Iraq and Syria are going to be, for the foreseeable future, failed states,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy analyst Soner Cagaptay said.

That entails “huge amounts of instability, civil war, jihadist threats,” he said.

Turkey’s best response is “a forward military presence in both countries,” he added.

There are also sectarian allegiances at stake. Erdogan is a Sunni Muslim, like most Turks, and his politics are rooted in religion.

He portrays Turkey as the protector of Sunnis in Iraq and Syria who face oppression at the hands of rulers backed by Iran, the region’s main Shiite power.

“Erdogan is unhappy — as would be any Turkish leader, secular, Islamist, you name it — to see Iran rising,” Cagaptay said.

On that, at least, Turkey and the US can see eye to eye. However, as the battle for Mosul approaches a climax, it is their disagreements that threaten to unstitch the fragile anti-IS coalition assembled in Washington. The Iraqi government that Erdogan fulminates against is a US ally and so are the Kurdish fighters in Syria that his army is targeting.

Not all the Turkish leader’s trademark verbal volleys are directed at Kurds or Shiites. Erdogan has also criticized NATO allies for failing to prevent the slaughter in Syria and for giving his government only lukewarm support as it faced down the coup attempt.

That is one reason why Erdogan’s domestic agenda is widening the rift between Turkey and the West, said Aaron Stein, a fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

“Talking tough never hurts a president running a campaign geared toward an inward-looking and hyper-nationalist constituency,” Stein said. However, it creates a “toxic mix for transatlantic relations.”

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

Keelung Mayor George Hsieh (謝國樑) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) on Tuesday last week apologized over allegations that the former director of the city’s Civil Affairs Department had illegally accessed citizens’ data to assist the KMT in its campaign to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) councilors. Given the public discontent with opposition lawmakers’ disruptive behavior in the legislature, passage of unconstitutional legislation and slashing of the central government’s budget, civic groups have launched a massive campaign to recall KMT lawmakers. The KMT has tried to fight back by initiating campaigns to recall DPP lawmakers, but the petition documents they

A recent scandal involving a high-school student from a private school in Taichung has reignited long-standing frustrations with Taiwan’s increasingly complex and high-pressure university admissions system. The student, who had successfully gained admission to several prestigious medical schools, shared their learning portfolio on social media — only for Internet sleuths to quickly uncover a falsified claim of receiving a “Best Debater” award. The fallout was swift and unforgiving. National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University and Taipei Medical University revoked the student’s admission on Wednesday. One day later, Chung Shan Medical University also announced it would cancel the student’s admission. China Medical

Construction of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County’s Hengchun Township (恆春) started in 1978. It began commercial operations in 1984. Since then, it has experienced several accidents, radiation pollution and fires. It was finally decommissioned on May 17 after the operating license of its No. 2 reactor expired. However, a proposed referendum to be held on Aug. 23 on restarting the reactor is potentially bringing back those risks. Four reasons are listed for holding the referendum: First, the difficulty of meeting greenhouse gas reduction targets and the inefficiency of new energy sources such as photovoltaic and wind power. Second,