In China, practitioners of the Falun Gong spiritual movement have long complained of propaganda campaigns, imprisonment and torture at the hands of the Chinese government.

In Flushing, Queens, which has perhaps the largest Falun Gong following in the US, members say their adversaries are a handful of spirited Chinese immigrants who tend a small folding table set up every day in front of a Chinese restaurant on a stretch of Main Street that is bustling with Chinese immigrants.

The opposition group distributes materials denouncing Falun Gong as an evil cult, an epithet that the organization incorporates into its name, the Chinese Anti-Cult World Alliance.

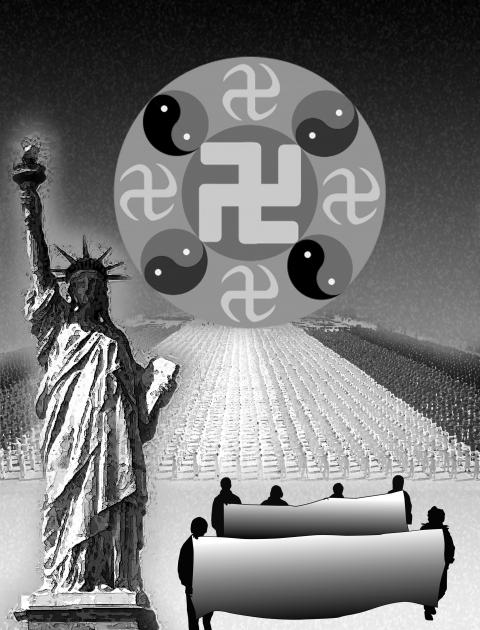

Illustration: Constance Chou

Having staked out their turf in Flushing, the two factions have long waged a bitter ideological battle.

Now, a new battle front has opened — in a Brooklyn courthouse.

Members of Falun Gong have filed a federal lawsuit against the anti-cult group seeking relief from what they call “an ongoing campaign of violent assaults, threats, intimidation and other abuses.”

The lawsuit accuses the alliance of collaborating with the Chinese government by persecuting Falun Gong in the US and seeking “to purge Flushing of Falun Gong.”

The suit, which details more than 20 assaults against, and confrontations with, the plaintiffs, is asking the court for an order that would keep the anti-Falun Gong group away. It also claims that Falun Gong members have been subjected to “mob violence” from the opposition group.

Tom Fini, a lawyer representing the alliance, called the lawsuit baseless and said the plaintiffs’ main complaint against his clients was their labeling of Falun Gong as a cult.

Fini added that “the plaintiffs are trying to intimidate my clients, punishing them with a federal lawsuit to quash their right to free speech.”

He said the Falun Gong members were suing over “a handful of confrontations that they initiated” and were citing “a few scuffles where there has not been one serious injury or hospital visit.”

Not so, said Terri Marsh, a lawyer for the plaintiffs.

“That it hasn’t risen to the level of a beheading is beside the point,” Marsh said, adding that the anti-cult group’s regimen of attacks and intimidation — even if it is yelling and shoving — interferes with her clients’ religious freedom.

She said her clients “are not trying to stop their right to free speech — they really just want the violence to stop.”

ELIMINATION

The feud in Flushing dates back to 2008, when members of the alliance accused Falun Gong members of disrupting fundraising efforts on Main Street for victims of a deadly earthquake in China, partly to prevent funds from potentially winding up in the hands of the Chinese government, the opposition group charged.

The anti-cult group’s table soon appeared on Main Street, offering literature criticizing the Falun Gong ideology as extremist and an embarrassment to Chinese immigrants.

Not far from the alliance’s table is a Falun Gong spiritual center with its own sidewalk tables, where volunteers distribute fliers protesting their group’s treatment by the Chinese government and describing the ruthless methods it uses to try to eliminate the spiritual practice in China.

To hear Falun Gong members in Flushing tell it, they are meek practitioners who follow a moral philosophy based on truth, tolerance and compassion. They say they are preyed upon by the anti-cult group simply because of their beliefs.

The alliance scoffs at this, saying the Falun Gong members pose as victims while being just as complicit in the altercations.

One of the defendants, Michael Chu, a leader of the anti-cult group, said the confrontations usually involved both groups pointing cameras at each other and sometimes calling the police.

He characterized them as typical New York City street arguments — standoffs or scuffles sometimes, but hardly attacks.

“They manufactured these incidents” into political clashes, said Chu, who runs a travel agency, a neighborhood watch and other community organizations.

Inside his office, he pulled out dozens of signs that he and members typically use in demonstrations against Falun Gong. They criticized the spiritual group for, among other things, believing in paranormal activity, eschewing modern medicine and distorting Chinese culture, Chu said.

Chu’s outspokenness has made him a target. In the Epoch Times, a free daily newspaper that supports the Falun Gong, he has been portrayed as a puppet for the Chinese Communist Party as part of a campaign to expand its influence in the US.

Marsh said that Chu recruited — sometimes using free meals as an incentive — members of his neighborhood watch group to participate in protests against the Falun Gong.

However, Fini called the suit an attempt to “silence my clients’ First Amendment right to express their opinion that many of the beliefs of Falun Gong are irrational and dangerous.”

To better illustrate those beliefs, Fini said, he wants to call as a witness the Falun Gong’s venerated founder and leader, Li Hongzhi (李洪志).

FREEDOM OF BELIEF

Although Falun Gong is known as a system that combines elements of Buddhism, mysticism and traditional exercise regimen, some followers also ascribe to the more unconventional teachings of Li, including alien visitation, ethnic separation and other beliefs that might clarify “why my clients have the constitutional right to call them a cult,” Fini said.

Fini said one plaintiff had already admitted in a deposition to sharing Li’s ideas about extraterrestrial visitors and the existence of different heavens for different races.

“My clients call these beliefs bizarre and dangerous,” Fini said. “If they follow a leader who teaches about aliens and segregated heavens, my clients get to call those ideas cult-like, bizarre and dangerous. That’s how freedom of speech works.”

However, Marsh said that “these doctrines that he characterizes as bizarre are part of virtually every Eastern religion, including Tibetan Buddhism, Buddhism and Taoism, and just because he thinks it’s strange doesn’t mean it’s not a religion.”

Marsh said Fini was threatening to depose Li as a way to intimidate her clients into dropping their case to avoid exposing their leader.

She said her clients considered Li an enlightened, transcendent figure and that Fini’s desire to depose him would be “a deliberate form of disrespect geared to harass them and denigrate their religion.”

Deposing Li could also elicit personal information that could endanger him, said Marsh, whose request to have the court block the subpoena to have Li deposed and to seal the case from public record was denied.

Fini has been unable to find the reclusive Li, who moved to the US in the late 1990s and whose whereabouts are unclear.

Marsh said she did not know the whereabouts of the leader and neither did her clients.

Li does appear sporadically at Falun Gong events, and the presumption is that he lives in the sprawling Dragon Springs center that Falun Gong operates in upstate New York.

Fini said his process server was turned away at the gate and told that Li did not live there.

Marsh does not want the Falun Gong leader to be questioned, “because the plaintiffs don’t want the truth about his many bizarre teachings to come out,” Fini said.

Having lived through former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s tumultuous and scandal-ridden administration, the last place I had expected to come face-to-face with “Mr Brexit” was in a hotel ballroom in Taipei. Should I have been so surprised? Over the past few years, Taiwan has unfortunately become the destination of choice for washed-up Western politicians to turn up long after their political careers have ended, making grandiose speeches in exchange for extraordinarily large paychecks far exceeding the annual salary of all but the wealthiest of Taiwan’s business tycoons. Taiwan’s pursuit of bygone politicians with little to no influence in their home

In a recent essay, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” a former adviser to US President Donald Trump, Christian Whiton, accuses Taiwan of diplomatic incompetence — claiming Taipei failed to reach out to Trump, botched trade negotiations and mishandled its defense posture. Whiton’s narrative overlooks a fundamental truth: Taiwan was never in a position to “win” Trump’s favor in the first place. The playing field was asymmetrical from the outset, dominated by a transactional US president on one side and the looming threat of Chinese coercion on the other. From the outset of his second term, which began in January, Trump reaffirmed his

It is difficult not to agree with a few points stated by Christian Whiton in his article, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” and yet the main idea is flawed. I am a Polish journalist who considers Taiwan her second home. I am conservative, and I might disagree with some social changes being promoted in Taiwan right now, especially the push for progressiveness backed by leftists from the West — we need to clean up our mess before blaming the Taiwanese. However, I would never think that those issues should dominate the West’s judgement of Taiwan’s geopolitical importance. The question is not whether

In 2025, it is easy to believe that Taiwan has always played a central role in various assessments of global national interests. But that is a mistaken belief. Taiwan’s position in the world and the international support it presently enjoys are relatively new and remain highly vulnerable to challenges from China. In the early 2000s, the George W. Bush Administration had plans to elevate bilateral relations and to boost Taiwan’s defense. It designated Taiwan as a non-NATO ally, and in 2001 made available to Taiwan a significant package of arms to enhance the island’s defenses including the submarines it long sought.