At the end of last year, Greece’s public debt was 176 percent of GDP, while Japan’s debt ratio was 248 percent. Neither government will ever repay all they owe. Write-offs and monetization are inevitable, putting both countries in a sort of global vanguard. With total public and private debt worldwide at 215 percent of world GDP and rising, the tools on which Greece and Japan depend will almost certainly be applied elsewhere as well.

Since 2010, official discussion of Greek debt has moved fitfully from fantasy to gradually dawning reality. The rescue program for Greece launched that year assumed that a falling debt ratio could be achieved without any private debt write-offs.

After a huge restructuring of privately held debt in 2011, the ratio was forecast to reach 124 percent by 2020, a target the IMF believed could be achieved, “but not with high probability.”

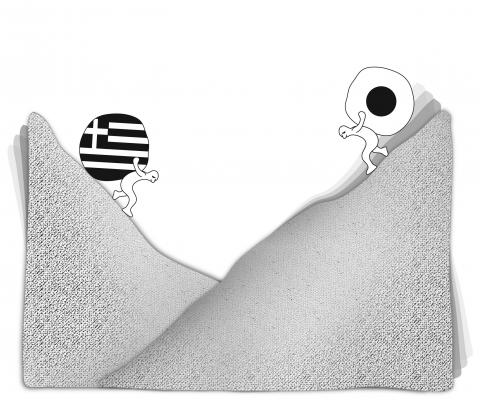

Illustration: June Hsu

Today, the IMF believes that a debt ratio of 173 percent is possible by 2020, but only if Greece’s official European creditors grant significant further debt relief.

Greece’s prospects for debt sustainability have worsened because the eurozone’s authorities have refused to accept significant debt write-downs. The 2010 program committed Greece to turn a primary fiscal deficit (excluding debt service) of 5 percent of GDP into a 6 percent surplus; but the austerity needed to deliver that consolidation produced a deep recession and a rising debt ratio. Now the eurozone is demanding that Greece turn its primary deficit last year of 1 percent of GDP into a 3.5 percent-of-GDP surplus, and to maintain that fiscal stance for decades to come.

However, as the IMF rightly says, that goal is wildly unrealistic, and pursuing it would prove self-defeating. If talented young Greeks must fund perpetual surpluses to repay past debts, they can literally walk away from Greece’s debts by moving elsewhere in the EU (taking tax revenues with them).

The IMF now proposes a more realistic 1.5 percent-of-GDP surplus, but that could put the debt ratio on a sustainable path only if combined with a significant write-down. However, eurozone leaders’ official stance continues to rule that out; they will consider only an extension of maturities and reduced interest rates at some future date.

If pursued to the limit, such adjustments can make any debt affordable — after all, a perpetual non-interest-bearing debt imposes no burden at all — while still enabling politicians to maintain the fiction that no debt had been written off. However, the maturity extensions and rate reductions granted so far have been far less than needed to ensure debt sustainability. The time has come for honesty: A significant write-down is inevitable, and the longer it is put off, the larger it eventually will be.

Greece’s unresolved debt crisis still poses financial stability risks, but its US$340 billion public debt is dwarfed by Japan’s US$10 trillion. While most Greek debt is now owed to official institutions, Japanese government bonds are held in private investment portfolios around the world. However, in Japan’s case, debt monetization, not an explicit write-off, will pave the path back to sustainability.

As with Greece, official fiscal forecasts for Japan have been fantasies.

In 2010, the IMF described how Japan could reduce net debt (excluding government bonds held by quasi-government organizations) to a “sustainable” 80 percent of GDP by 2030, if it turned that year’s primary fiscal deficit of 6.5 percent of GDP into a 6.4 percent-of-GDP surplus by 2020, and maintained that surplus throughout the subsequent decade.

However, virtually no progress toward this goal had been achieved by 2014.

Instead, the new scenario foresaw that year’s 6 percent-of-GDP deficit swinging to a 5.6 percent surplus by 2020. In fact, fiscal tightening on anything like this scale would produce a deep recession, increasing the debt ratio.

The Japanese government has therefore abandoned its plan for an increase in sales tax next year, and the IMF has ceased publishing any scenario in which the debt ratio falls to some defined “sustainable” level. Its latest forecasts suggest a 2020 primary deficit still at more than 3 percent of GDP.

However, the debt owed by the Japanese government to private investors is in free fall. Of Japan’s net debt of 130 percent of GDP, about half (66 percent of GDP) is owed to the Bank of Japan (BOJ), which the government in turn owns. And with the BOJ buying government debt at a rate of ¥80 trillion (US$767.98 billion) per year, while the government issues less than ¥40 trillion per year, the net debt of the Japanese consolidated public sector will fall to 28 percent of GDP by the end of 2018, and could reach zero sometime in the early 2020s.

However, the current official fiction is that all the debt will eventually be resold to the private sector, becoming again a real public liability that must be repaid out of future fiscal surpluses. If Japanese companies and households believe this fiction, they should rationally respond by saving to pay future taxes, thereby offsetting the stimulative effect of today’s fiscal deficits.

Realism would be a better basis for policy, converting some of the BOJ’s holdings of government bonds into a perpetual non-interest-bearing loan to the government. Tight constraints on the quantity of such monetization would be essential, but the alternative is not no monetization; it is undisciplined de facto monetization, accompanied by denials that any monetization is taking place.

In both Greece and Japan, excessive debts will be reduced by means previously regarded as unthinkable. It would have been far better if debts had never been allowed to grow to excess, if Greece had not joined the eurozone on fraudulent terms and if Japan had deployed sufficiently aggressive policy to stimulate growth and inflation 20 years ago.

Throughout the world, radically different policies are needed to enable economies to grow without the excessive private debt creation that occurred before 2008. However, having allowed excessive debt to mount, sensible policy design must start from the recognition that many debts, both public and private, simply cannot be repaid.

Adair Turner, a former chairman of the UK’s Financial Services Authority and former member of the UK’s Financial Policy Committee, is chairman of the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump created some consternation in Taiwan last week when he told a news conference that a successful trade deal with China would help with “unification.” Although the People’s Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan, Trump’s language struck a raw nerve in Taiwan given his open siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression seeking to “reunify” Ukraine and Russia. On earlier occasions, Trump has criticized Taiwan for “stealing” the US’ chip industry and for relying too much on the US for defense, ominously presaging a weakening of US support for Taiwan. However, further examination of Trump’s remarks in

It is being said every second day: The ongoing recall campaign in Taiwan — where citizens are trying to collect enough signatures to trigger re-elections for a number of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — is orchestrated by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), or even President William Lai (賴清德) himself. The KMT makes the claim, and foreign media and analysts repeat it. However, they never show any proof — because there is not any. It is alarming how easily academics, journalists and experts toss around claims that amount to accusing a democratic government of conspiracy — without a shred of evidence. These

China on May 23, 1951, imposed the so-called “17-Point Agreement” to formally annex Tibet. In March, China in its 18th White Paper misleadingly said it laid “firm foundations for the region’s human rights cause.” The agreement is invalid in international law, because it was signed under threat. Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, head of the Tibetan delegation sent to China for peace negotiations, was not authorized to sign the agreement on behalf of the Tibetan government and the delegation was made to sign it under duress. After seven decades, Tibet remains intact and there is global outpouring of sympathy for Tibetans. This realization

Taiwan is confronting escalating threats from its behemoth neighbor. Last month, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army conducted live-fire drills in the East China Sea, practicing blockades and precision strikes on simulated targets, while its escalating cyberattacks targeting government, financial and telecommunication systems threaten to disrupt Taiwan’s digital infrastructure. The mounting geopolitical pressure underscores Taiwan’s need to strengthen its defense capabilities to deter possible aggression and improve civilian preparedness. The consequences of inadequate preparation have been made all too clear by the tragic situation in Ukraine. Taiwan can build on its successful COVID-19 response, marked by effective planning and execution, to enhance