During China’s traditional festival for honoring the dead — Qingming or Tomb Sweeping Day — Zheng Zhisheng (鄭志勝) usually visits a vine-draped cemetery where pillars declare the dead’s eternal loyalty to Mao Zedong (毛澤東). He walks among the mass graves, sharing memories and sometimes tears, with mourners who greet him as their “corpse commander.”

They are veterans of the Cultural Revolution and their kin, who at the Qingming Festival each year gather at the graves of family and friends killed in the convulsive movement that Mao unleashed upon China. Cities and regions became battle zones between rival Red Guards — militant student groups that attacked intellectuals, officials and others — and up to 1.5 million people died nationwide, according to one recent estimate.

Yet this cemetery in Chongqing, an industrial city on the Yangtze River, is the only sizable one left solely for those killed then. Zheng, 73, is one of the aging custodians of their harrowing stories. He buried many of the 400 to 500 bodies here, on the edge of a park in the Shapingba District.

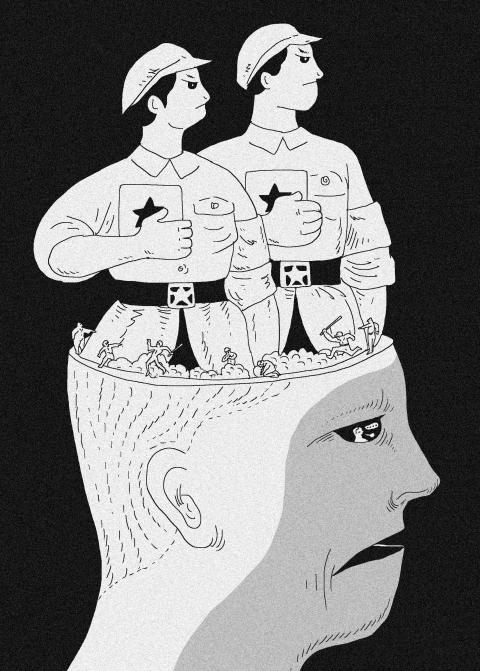

Illustration: Mountain People

“I think about their memories and the lessons we should absorb and I try to comfort the relatives,” he said in an interview. “It would be impossible to erase that time from our hearts.”

Fifty years after the start of the Cultural Revolution, the cemetery embodies China’s evasive reckoning with its legacy. Here the tension between official silence and grassroots remembrance is palpable.

The cemetery is usually locked, but on Tomb Sweeping Day, a door opens for families and friends of the dead to hold vigils, light incense and leave wreaths and other offerings at the graves.

This year, officials took special precautions, attaching coils of barbed wire along the top of the wall around the cemetery. They mounted surveillance cameras at the entrance, as well as a sign in Chinese and English that read: “Historical preservation, no photographing.”

On Tomb Sweeping Day, which this year was on Monday, clusters of older people registered at a booth to enter the cemetery, some joined by couples with children. Dozens of guards hustled onlookers and journalists away, telling them they could not even take photographs of the exterior.

“There’s nothing to see,” one said. “Go away.”

About 1,700 people were put to death across Chongqing during the worst clashes, which receded in 1968, according to an official estimate by He Shu, the city’s unofficial chronicler of that time.

The total killed was probably higher.

As the bodies piled up, rotting in the heat, faction leaders conscripted Zheng, an engineering student, to dispose of them.

In a cool air-raid shelter, he learned to inject them with formaldehyde and he chose the park site to bury them, using prisoners from the rival faction as helpers.

Some of the dead were photographed in Red Guard uniforms — military-style clothes, belts and caps, and badges — while their comrades and family stood proudly beside them.

“I personally laid to rest more than 280 people,” Zheng said. “I bathed and injected them with formaldehyde, I dressed them, I put them in graves, so my nickname was the corpse commander. We were all sacrificial objects in a political struggle.”

Across Chongqing, about 20 Cultural Revolution cemeteries were razed as the movement waned and Mao died. This one survived in part because of its out-of-the-way location and a tolerant city party secretary in the 1980s, said Everett Yuehong Zhang (張躍宏), an anthropologist from Chongqing at Princeton University.

However, the past it contains has become a delicate topic with the coming of the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution. Focusing on that time offends Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) drive against dwelling on mistakes by Mao and the party. Although his own family suffered grievously during the Cultural Revolution, he would rather focus on past glories.

No official memorial events have been announced to acknowledge the milestone; none of the reports about Qingming by the state news media mentioned the Cultural Revolution dead.

Mao started the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” in 1966 to purge China of “revisionist” compromises that he said imperiled his revolution. He gave his blessing to militant students to enforce his will, but the movement took a chaotic turn and vicious rivalries broke out between Red Guard factions competing to represent Mao’s vision.

In Chongqing, the schisms erupted into war in the summer of 1967, when militants seized weapons from armament plants. Most people buried in the Shapingba cemetery supported the “August 15” faction that battled the “rebel to the end” faction.

“We had eight big weapons factories, making tanks and guns and other arms, and many of the workers were ex-soldiers who knew how to fight,” said Wu Qi (吳琪), a businessman from Chongqing who watched the fighting as a teenager. “It was like a real military battle.”

The victims who have most haunted Zheng did not end up in his cemetery.

In August 1967, after his August 15 faction had been under ferocious attack, in a fit of fury he handed two prisoners to a crowd that stomped them senseless. A day or two later, he let two Red Guards beat them to death. Their bodies were thrown into a ditch on a university campus.

“This was the greatest regret of my life,” Zheng said.

Having lived through former British prime minister Boris Johnson’s tumultuous and scandal-ridden administration, the last place I had expected to come face-to-face with “Mr Brexit” was in a hotel ballroom in Taipei. Should I have been so surprised? Over the past few years, Taiwan has unfortunately become the destination of choice for washed-up Western politicians to turn up long after their political careers have ended, making grandiose speeches in exchange for extraordinarily large paychecks far exceeding the annual salary of all but the wealthiest of Taiwan’s business tycoons. Taiwan’s pursuit of bygone politicians with little to no influence in their home

In a recent essay, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” a former adviser to US President Donald Trump, Christian Whiton, accuses Taiwan of diplomatic incompetence — claiming Taipei failed to reach out to Trump, botched trade negotiations and mishandled its defense posture. Whiton’s narrative overlooks a fundamental truth: Taiwan was never in a position to “win” Trump’s favor in the first place. The playing field was asymmetrical from the outset, dominated by a transactional US president on one side and the looming threat of Chinese coercion on the other. From the outset of his second term, which began in January, Trump reaffirmed his

Despite calls to the contrary from their respective powerful neighbors, Taiwan and Somaliland continue to expand their relationship, endowing it with important new prospects. Fitting into this bigger picture is the historic Coast Guard Cooperation Agreement signed last month. The common goal is to move the already strong bilateral relationship toward operational cooperation, with significant and tangible mutual benefits to be observed. Essentially, the new agreement commits the parties to a course of conduct that is expressed in three fundamental activities: cooperation, intelligence sharing and technology transfer. This reflects the desire — shared by both nations — to achieve strategic results within

It is difficult not to agree with a few points stated by Christian Whiton in his article, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” and yet the main idea is flawed. I am a Polish journalist who considers Taiwan her second home. I am conservative, and I might disagree with some social changes being promoted in Taiwan right now, especially the push for progressiveness backed by leftists from the West — we need to clean up our mess before blaming the Taiwanese. However, I would never think that those issues should dominate the West’s judgement of Taiwan’s geopolitical importance. The question is not whether