Footage of a man handing bananas to two naked men in the middle of an Amazonian river went viral in late June 2014. At the time, the Brazilians claimed it was a once in a generation event — that the moment of “first contact” was caught on camera. These were some of the last so-called “uncontacted” peoples left on the planet — men and women who live with no direct contact with the outside world. Experts suggest there are perhaps 70 such groupings left, numbering anything from 2,000 to 3,000 people in total, nearly all of whom live in the headwaters of the Amazon.

The emergence of this group of 35 of the Sapanahua tribe in 2014 has raised serious questions about how we should approach these people. In making our film, First Contact: Lost Tribe of the Amazon, we not only got the first access to the 35 to find out why they made contact and what their lives were like, but we went over the border to reserves in Peru, where we discovered a much bigger crisis.

For some reason, different uncontacted tribes and groupings are coming out on all sides of the reserves. The conventional, often correct, explanation is that they are being driven out by confrontations with illegal loggers and drug traffickers. However, there is evidence that something more fundamental is happening. What is certain is that the authorities are struggling to cope.

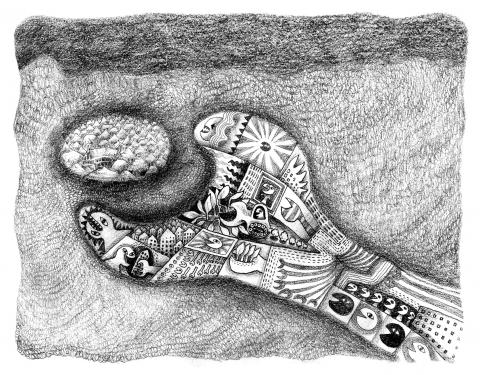

Illustration: Mountain people

In Brazil, the story of the 35 has been a success so far. The 14 men, nine women and 12 children are flourishing. They are living under the protection of FUNAI — the Brazilian department of indigenous peoples — at a camp they are creating four hours upriver from where they emerged. They seem to have overcome the most immediate danger: lack of immunity to our common diseases. It is now thought that simple influenza and the common cold, brought by outsiders from the Spanish conquistadores onwards, wiped out the vast majority of the indigenous peoples in the Amazon over the centuries.

So FUNAI flew in an expert doctor who vaccinated all 35, after gaining enough trust to persuade them that the injections were not designed to kill them. That trust is difficult. Misunderstandings abound. More than 100 FUNAI agents have been killed by tribes in the past decade. FUNAI proudly claims that this is the only time no one on either side has died after first contact, although some anthropologists and non-governmental organizations worry that members of the 35, when they disappear off hunting, could meet other members of the tribe and pass on deadly germs.

In their new home, where they continue to hunt and live much as they did before, the 35 have quickly adapted to the advantages of clothing, machetes and pots and pans. One of the women loves her flip-flops, while a nine-year-old boy, Curi Curi, happily seized our stills camera and within 10 minutes was producing photographs. They may well be what we once were, but they quickly can become like us. For good or bad.

In the desire to protect, it is amazing what we invest in these men and women. When the team first traveled down the rivers for more than a week to meet them, we felt as if we were crossing a time barrier. Here were people untouched by our rapacious civilization. Here were people who might tell us something profound about ourselves. Do they hold some profound ancient wisdoms we have lost? Some understanding of what we are as human beings? Or is such an idea simply an expression of our guilt?

While with them we discovered that it was a confrontation with armed men deep in the rainforest that finally drove them out. There had been a massacre in which fathers and mothers had been killed. The ones who first emerged were young and incredibly brave to seek peaceful contact with “the whites” who have always brought them death.

Their leader, Xina, told us that his parents always talked about how “the whites had always wanted to kill us.” Indeed a few days with the FUNAI anthropologists made clear that these rivers are not quite so untouched as they seem; nor were these tribes quite so isolated. They were almost certainly refugees from the horror that was the rubber boom of the early 20th century, when tribes that did not agree to work as slaves were hunted down and exterminated. These were the ones who ran away. And have stayed away until now.

What we also discovered from them, and also from others when we traveled south into Peru, was that they are not living in some prelapsarian Eden, innocent and untouched by the burdens of modern life. They continue to live in an almost constant state of terror. And fear. Fear of both their own world and fear of the outside.

It is a toxic mix: It turns out they are scared of snakes and jaguars, don’t like sleeping naked in the storms and think thunderstorms are the work of the gods.

And they do know about the outside world. They watch it, often silently. They see the clothes, the axes and the houses. And they want them, so it emerges they are regularly stealing and raiding. And that creates the next stage level of fear — because often when they put on the clothes they fall ill and sometimes die. And of course they cannot understand why.

For the past generation, the established policy has been to create vast reserves for the tribes, into which outsiders are not permitted, and not to contact them when they are seen or they approach. This policy provides some element of protection against the multinational oil, gas and mining companies which, like the first Spaniards, see the rainforests as the new frontier.

Indeed as recently as 10 years ago, the Peruvian government and its commercial friends ridiculed environmentalists and groups such as Survival International, which attempt to protect the interests of indigenous peoples in the Amazon. The government said there were no uncontacted peoples in Peru, so there was no need to protect them or close off their lands.

In the past couple of years the uncontacted have been unconsciously taking advantage of the policy. Local indigenous tribes, long part of the Peruvian and Brazilian state, have been lectured on how they should run away and escape if ever approached. They are told they will be prosecuted if they attack or even retaliate. As a result, the uncontacted feel able to walk into villages, particularly when the men are away. There is a genuine sense of crisis in some regions on the edge of the reserve.

In November 2014, the Peruvian border community of Monte Salvado, on the east of the reserve, was evacuated when a force of 150 people from the Mashco-Piro tribe, armed to the teeth, appeared on the other side of the river. What were they doing there? The lack of communication makes it almost impossible to tell. Such a grouping was not the result of a confrontation with loggers or traffickers, who have been cleared out of the area. When we traveled back with the villagers, some promised they would fight if the Mashco appeared like that again.

To the south, across the Manu reserve, the confrontation has turned to real violence with the murder of a young man in his village of Shipiatari. Here a much smaller group of Mashco-Piro has been drawn to a riverbank, which is used by commercial traffic, including tourists on their way to some of the finest jungle lodges in the world. A local evangelist has been visiting them trying to save their souls.

The Peruvian Ministry of Culture is struggling to cope and is for the first time breaking its no-contact code. It is keen to prevent any further violence between the Mashco-Piro and the local people, and has created a post along the river, which not only prevents tourist boats stopping to gawp, but also has a doctor.

We witnessed the first time the doctor went over to treat a woman, who had been attacked by an anteater. The government hopes that such contact will build some trust, though it fears the possible passing on of germs at the same time, which might undermine that trust.

The mantra must clearly remain that these men and women should only come out if they choose to. However, if it is true that fear is the dominant reality of these people’s lives, is our overwhelming desire to protect them as they are the right way to continue?

Surely the Brazilians and Peruvians, now armed with the medical ability to quickly inoculate them, should be working out how to help them, to ensure their survival as they continue to emerge. Unless they do, there is a real chance of violent confrontation and another tragedy in the Amazon.

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) concludes his fourth visit to China since leaving office, Taiwan finds itself once again trapped in a familiar cycle of political theater. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has criticized Ma’s participation in the Straits Forum as “dancing with Beijing,” while the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) defends it as an act of constitutional diplomacy. Both sides miss a crucial point: The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world. The disagreement reduces Taiwan’s

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) is visiting China, where he is addressed in a few ways, but never as a former president. On Sunday, he attended the Straits Forum in Xiamen, not as a former president of Taiwan, but as a former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairman. There, he met with Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Chairman Wang Huning (王滬寧). Presumably, Wang at least would have been aware that Ma had once been president, and yet he did not mention that fact, referring to him only as “Mr Ma Ying-jeou.” Perhaps the apparent oversight was not intended to convey a lack of

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) last week announced that the KMT was launching “Operation Patriot” in response to an unprecedented massive campaign to recall 31 KMT legislators. However, his action has also raised questions and doubts: Are these so-called “patriots” pledging allegiance to the country or to the party? While all KMT-proposed campaigns to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers have failed, and a growing number of local KMT chapter personnel have been indicted for allegedly forging petition signatures, media reports said that at least 26 recall motions against KMT legislators have passed the second signature threshold