What is going on with the weather?

With tornado outbreaks in the southern US, Christmas temperatures that sent trees into bloom in New York’s Central Park, drought in parts of Africa and historic floods drowning the old industrial cities of England, last year closed with a string of weather anomalies all over the world.

The year, expected to have been the hottest on record, may be over, but the trouble would not be. Rain in the central US has been so heavy that major floods are likely along the lower Mississippi River in coming weeks. California might lurch from drought to flood by late winter. Most serious, millions of people could be threatened by a developing food shortage in southern Africa.

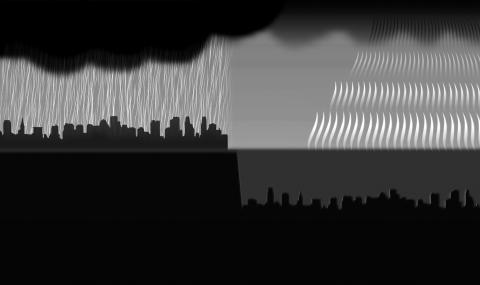

Illustration: Yusha

Scientists say the most obvious suspect in the turmoil is the climate pattern called El Nino, in which the Pacific Ocean for the past few months has been dumping immense amounts of heat into the atmosphere. Because atmospheric waves can travel thousands of kilometers, the added heat and accompanying moisture have been playing havoc with the weather in many parts of the world.

SEEKING ANSWERS

However, that natural pattern of variability is not the whole story. This El Nino, one of the strongest on record, comes atop a long-term heating of the planet caused by mankind’s emissions of greenhouse gases.

A large body of scientific evidence says those emissions are making certain kinds of extremes, such as heavy rainstorms and intense heat waves, more frequent.

Coincidence or not, every kind of trouble that the experts have been warning about for years seems to be occurring at once.

“As scientists, it’s a little humbling that we’ve kind of been saying this for 20 years now and it’s not until people notice daffodils coming out in December that they start to say, ‘maybe they’re right,’” said Myles Allen, a professor of geosystem science at Oxford University in Britain and head of the Climate Dynamics Group in the physics department.

Allen’s group, in collaboration with US and Dutch researchers, recently completed a report calculating that extreme rainstorms last month in the British Isles had become about 40 percent more likely as a consequence of human emissions. That document — inspired by a storm early last month that dumped stupendous rains, including 33cm on one town in 24 hours — was barely finished when the skies opened up again.

Emergency crews have since been scrambling to rescue people from flooded homes in Leeds, York and other cities. A dispute has erupted in the British parliament about whether the country is doing enough to prepare for a changing climate.

Allen does not believe that El Nino had much to do with the British flooding, based on historical evidence that the influence of the Pacific Ocean anomaly is fairly weak in that part of the world. In the western hemisphere, the strong El Nino is likely a bigger part of the explanation for the strange winter weather.

The northern tier of the US is often warm during El Nino years and, indeed, weather forecasters months ago predicted such a pattern for this winter. However, they did not go so far as to forecast that the temperature in Central Park on the day before Christmas would hit 22oC.

Likewise, past evidence suggests that El Nino can cause the fall tornado season in the Gulf Coast states to extend into December, as happened last year, with deadly consequences in states like Texas and Mississippi.

ARCTIC OSCILLATION

Matthew Rosencrans, head of forecast operations for the US government’s Climate Prediction Center in College Park, Maryland, said that El Nino was not the only natural factor at work.

This winter, a climate pattern called the Arctic Oscillation is also keeping cold air bottled up in the high north, allowing heat and moisture to accumulate in the middle latitudes.

That might be a factor in the recent heavy rains in US states like Georgia and South Carolina, as well as in some of the other weather extremes, he said.

Scientists do not quite understand the connections, if any, between El Nino and variations in the Arctic Oscillation. They also do not fully understand how the combined effects of El Nino and human-induced warming are likely to play out over the coming decades.

Although El Ninos occur every three to seven years, most of them are of moderate intensity. They form when the westward trade winds in the Pacific weaken, or even reverse direction. That shift leads to a dramatic warming of the surface waters in the eastern Pacific.

TRACKING STORMS

“Clouds and storms follow the warm water, pumping heat and moisture high into the overlying atmosphere,” as NASA recently said. “These changes alter jet stream paths and affect storm tracks all over the world.”

The current El Nino is only the third powerful El Nino to have occurred in the era of satellites and other sophisticated weather observations. It is a small data set from which to try to draw broad conclusions, and experts said they would likely be working for months or years to understand what role El Nino and other factors played in last year’s weather extremes.

It is already clear, though, that the year would be the hottest ever at the surface of the planet, surpassing 2014 by a considerable margin. That is a function both of the short-term heat from El Nino and the long-term warming from human emissions. In both the Atlantic and Pacific, the unusually warm ocean surface is throwing extra moisture into the air, said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

Storms over land can draw their moisture from as far as 3,200km away, he said, so the warm ocean is likely influencing such events as the heavy rainstorms in the Southeast US, as well as the record number of strong hurricanes and typhoons that occurred this year in the Pacific basin, with devastating consequences for island nations like Vanuatu.

“The warmth means there is more fuel for these weather systems to feed upon,” Trenberth said. “This is the sort of thing we will see more as we go decades into the future.”

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big