It was recently reported that Janette Tough — best known for her 1980s role as Wee Jimmy Krankie — has “yellowed up” to play a male Japanese fashion designer in Jennifer Saunders’ upcoming Absolutely Fabulous film. This led to the “yellowface” debate rearing its ugly head in the media again.

I have found myself having to explain, once more, to fellow journalists and friends, why an actor painting their face yellow in order to portray an East Asian character is offensive.

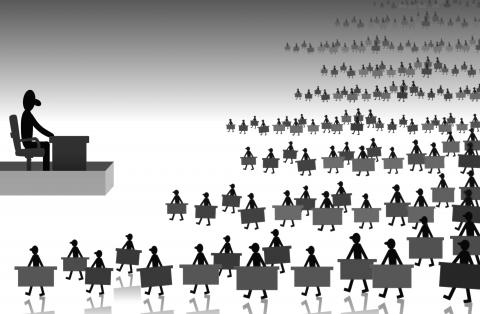

A persistent lack of representation in the media means that racism against East Asian and Southeast Asian people is not taken as seriously as other forms of discrimination. The problem is not just a lack of visibility, but our under-representation among those in positions of power. There is a dearth of commentators to speak up on behalf of Asian people, and a lack of commissioners, producers, scriptwriters and casting directors able to handle the problem sensitively — either by being Asian themselves or being aware of the issues.

Illustration: Yusha

For the record, yellowing up is offensive. It plays into years of unequal power dynamics in spaces such as acting, where the dominant ethnicity has historically enforced rules that keep minority ethnic groups excluded and anything that maintains this inequality is wrong.

Yellowing up is the same as blacking up: It maintains the assumption that only white people are allowed to play parts written for minority actors. And it perpetuates the idea that minorities should be silent, fetishized and spoken about only by the dominant ethnicity: The idea that we do not, and perhaps should never, have a voice of our own.

Bastardizing a feature of any ethnic group is racist. Painting a face in yellow makeup to denote an East or Southeast Asian person is dehumanizing. It is offensive to characterize an entire ethnic group, or to lump groups together, using a physical stereotype.

Earlier this year, actor Gemma Chan said that some of the statistics regarding east Asian actors made her think: “You are more likely to see an alien in a Hollywood film than an Asian woman.”

If society is not accurately represented on screen then we are left with a distorted picture of the world.

When I was growing up, I cannot remember seeing a single positive character played by an East or Southeast Asian person. At one end of the negative spectrum was white actor Mickey Rooney’s disgracefully racist character IY Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which underlined all the obvious problems of yellowface. However, then there were also the more subtle stereotypes, such as sexually promiscuous and subversive female Asian characters, or ruthlessly intelligent, but evil, male Asian characters.

In my own fleeting attempt to work as an actor, I was told by an agent that I would have to learn all the East Asian and Southeast Asian accents as, given a lack of available Western parts, this would enable me to secure the most roles.

The situation is now, relatively, a little better, with spokespeople such as the comedian Margaret Cho and organizations such as British East Asian Artists, but the lack of East Asian and Southeast Asian people on screen is brought into sharp focus each year with the arrival of Christmas advertisements. Over the past nine years, John Lewis’ Christmas ads have featured an East Asian or Southeast Asian person only once and for less than two seconds — as an extra, out of focus, riding a bus. Last year, I watched John Lewis’ lonely penguin ad being filmed in the park 30m from my home in Tower Hamlets, an area of over two-thirds ethnic minorities, and it failed to include a single East or Southeast Asian person.

EastEnders, which is set in east London, an area with a large East Asian community, is one of the UK’s highest-rated TV shows, yet has never featured an East or Southeast Asian character apart from a female DVD seller, in a role that lasted six months. Hardly anyone, it seems, ever complains about these omissions.

The way the yellowface debate has been discussed in the media in the last few weeks has, at times, felt almost as offensive as the act of yellowing up itself. It has raised three important issues.

First, it is not necessarily your fault if you are not aware of how outraged some people are by yellowface. The problem is that we hear only from the people who cannot see the offense: non-Asian people. And these are the people who set the agenda for what is offensive. Other voices are forced to the margins.

Second, too much emphasis is placed on social media as a measure of public opinion. An exclusive club has formed on Twitter based on blue ticks and large follower numbers. And those with the power to set the agenda are more likely to listen to the people with the loudest social media voices. It is important for East and Southeast Asian people, including me, to speak up about this issue.

Third, there are some inequalities that need to be addressed with urgency. The history of East and Southeast Asians is unique, and in some ways we are seen as having it easy in comparison to other minority groups. For this reason, we tend to shy away from fights over equality and representation.

Many of us, lacking role models and encouragement through diversity schemes, would never have considered a career in the media. However, the discrimination we experience is real and it is a problem. We must not feel as though our fight is not as crucial as those of other people — and we should not be afraid to speak up.

A response to my article (“Invite ‘will-bes,’ not has-beens,” Aug. 12, page 8) mischaracterizes my arguments, as well as a speech by former British prime minister Boris Johnson at the Ketagalan Forum in Taipei early last month. Tseng Yueh-ying (曾月英) in the response (“A misreading of Johnson’s speech,” Aug. 24, page 8) does not dispute that Johnson referred repeatedly to Taiwan as “a segment of the Chinese population,” but asserts that the phrase challenged Beijing by questioning whether parts of “the Chinese population” could be “differently Chinese.” This is essentially a confirmation of Beijing’s “one country, two systems” formulation, which says that

Media said that several pan-blue figures — among them former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chairwoman Hung Hsiu-chu (洪秀柱), former KMT legislator Lee De-wei (李德維), former KMT Central Committee member Vincent Hsu (徐正文), New Party Chairman Wu Cheng-tien (吳成典), former New Party legislator Chou chuan (周荃) and New Party Deputy Secretary-General You Chih-pin (游智彬) — yesterday attended the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) military parade commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. China’s Xinhua news agency reported that foreign leaders were present alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, North Korean leader Kim

Taiwan stands at the epicenter of a seismic shift that will determine the Indo-Pacific’s future security architecture. Whether deterrence prevails or collapses will reverberate far beyond the Taiwan Strait, fundamentally reshaping global power dynamics. The stakes could not be higher. Today, Taipei confronts an unprecedented convergence of threats from an increasingly muscular China that has intensified its multidimensional pressure campaign. Beijing’s strategy is comprehensive: military intimidation, diplomatic isolation, economic coercion, and sophisticated influence operations designed to fracture Taiwan’s democratic society from within. This challenge is magnified by Taiwan’s internal political divisions, which extend to fundamental questions about the island’s identity and future

Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) Chairman Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) is expected to be summoned by the Taipei City Police Department after a rally in Taipei on Saturday last week resulted in injuries to eight police officers. The Ministry of the Interior on Sunday said that police had collected evidence of obstruction of public officials and coercion by an estimated 1,000 “disorderly” demonstrators. The rally — led by Huang to mark one year since a raid by Taipei prosecutors on then-TPP chairman and former Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) — might have contravened the Assembly and Parade Act (集會遊行法), as the organizers had