August 1975: Harold Wilson was the British prime minister; US president Gerald Ford had been in the White House for a year following Richard Nixon’s resignation as president; Steven Spielberg’s Jaws was the summer blockbuster as inflation in Britain hit a post-war peak of 27 percent.

Statutory incomes policy was Wilson’s response to the cost of living crisis in what now seems like a completely different world. With inflation nonexistent, today’s central banks have a big decision to make: Is it safe to go back in the water and start raising interest rates for the first time since the global financial crisis and recession of 2007 to 2009?

Some would certainly love to go for a dip. There is nothing the US Federal Reserve would like more than to be able to announce next month than the first increase in the cost of borrowing in nine years. The Bank of England feels the same way.

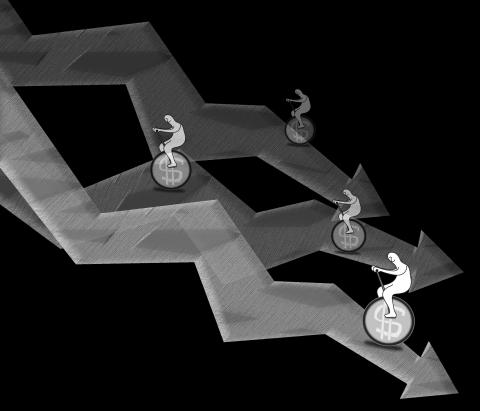

Illustration: June Hsu

The reasoning is simple. The end of ultra-low interest rates would be a sign that life was back to normal. When central banks cut their policy rates virtually to zero it was as an emergency measure. Raising rates would symbolize that the emergency is now over.

The process of interest-rate normalization is taking much longer than expected. Last month, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney tested the water when he said the bank would be considering a rate rise around the turn of the year.

However, he appears to be struggling to persuade a majority of the monetary policy committee to share his view. The Fed looks closer to a rate rise, but in neither the US nor the UK is the economic data conclusive.

Indeed, the latest set of figures for the UK labor market would argue for Threadneedle Street to be cautious. Unemployment rose for the second month in a row, there was a fall in employment that would have been bigger had it not been for an increase in non-UK citizens in work, and earnings growth either stalled or fell, depending on the measure used.

When the latest set of inflation figures are released on Tuesday, they are expected to show no change in the cost of living as measured by the consumer prices index over the past year. Recent falls in oil and commodity prices, coupled with the cheapening of imports more generally due to a stronger pound, are likely to result in inflation turning negative again over the coming months.

The Fed looks closer to what Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta president Dennis Lockhart calls “liftoff.”

However, as in the UK, inflation is well below target even when volatile items such as food and fuel are excluded from the calculation of the cost of living index.

As far as the US labor market is concerned, the good news is that the unemployment rate is below 6 percent, a level consistent in the past with the idea that rates should be heading upwards. The bad news is that the unemployment rate is distorted by people giving up looking for work, with the employment to population ratio lower than it was before the crash. Weak wage growth also suggests that demand for labor is far from buoyant.

There are arguments for higher rates. One is the risk that consumers and businesses start to assume that zero interest rates are here for good and start making reckless decisions on that basis. Those decisions lead to an overheating economy that in turn forces central banks to raise rates. Because households and firms are mentally ill-prepared, even a modest tightening of policy could have a severe impact.

A variant on this argument is that central banks need to give themselves headroom in the event that the global economy takes a turn for the worse. Interest rates normally go up during recoveries, thus providing the scope to bring them down again when a new recession looms. If rates remain at rock bottom level, central banks will have to find other ways to boost activity in the event of a new recession. As a first resort, they would restart quantitative easing — which involves increasing the money supply in order to stimulate economic activity — even though the experience of the last downturn is that these money-creation schemes do not provide much of a bang for the buck. There would be pressure for policy to become even more unconventional — perhaps through direct transfers of cash to consumers — were things to turn really nasty.

The Bank of England and the Fed have so far been unmoved by these arguments for higher interest rates. They certainly do not want to give the impression that the current state of affairs is to last forever, but find it hard to justify action when inflation is so low. There is also justifiable concern that increasing borrowing costs just so they can be cut again could trigger the recession that central banks are eager to avoid.

Consequently, policy depends on what the economy looks like from month to month. For example, the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee expects inflation to gradually increase over the next couple of years. Although inflation is currently zero, Threadneedle Street thinks three-quarters of the deviation from its 2 percent target can be explained by abnormally weak costs of energy, food and other imports. The Bank of England says this state of affairs can not last and therefore inflation is expected to rise. In addition, lower unemployment is set to make it harder for employers to find suitable labor. That is expected to lead to pressure for higher wages.

There has been an increase in annual earnings growth over the past year, but it would be quite a stretch to see it as the start of a wage price spiral. When inflation peaked in 1975, wages were rising at an annual rate of 30 percent. In June this year, average weekly earnings were £488 (US$726.06), £9 higher than a year earlier, but no higher than they were at the end of last year.

ADM Investor Services International chief economist Stephen Lewis said: “The rise in job insecurity since the 1980s, more especially after the global financial crisis, appears to have curbed the propensity of the workforce to demand higher pay relative to any given supply-demand balance in the labor market.”

“If the labor market is weak and the workforce is cowed, employers will naturally prefer to keep for the owners of the firm’s capital [often including themselves] the surplus profits generated by improved productivity,” he said.

This smells right. In the private sector, where levels of trade union membership and collective bargaining are low, the UK now has what amounts to an incomes policy that is voluntary, to the extent that workers are prepared to sacrifice pay rises in order to keep their jobs. In the public sector, where union density is higher, an old-fashioned statutory incomes policy is in force.

That is the only similarity with 1975. Wages are not going to head sharply upwards. And nor are interest rates.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its