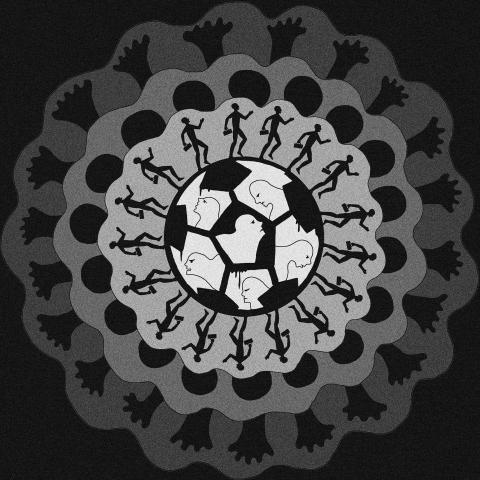

Every night as Ram, Kamal and Krishna take off their boots outside their rooms, they can see the shimmering silhouette of Qatar’s “Aspire” soccer complex.

Under its glowing domes, Qatari youths are drilled in preparation for the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The boys wear £200 (US$338) soccer shoes and are trained by a former coach from Spain’s top league on a full-sized air-conditioned pitch sometimes used by Manchester United and Bayern Munich.

In eight years, these boys are expected to carry the hopes of the richest per capita nation in the world in the opening match of soccer’s most prestigious event.

Aspire is just a couple of roads from the lodgings where Ram and his friends live the other side of Qatar’s World Cup dream. They came to Doha from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka to help fit out a skyscraper overlooking the Persian Gulf. The al-Bidda Tower is a twisting vortex of glass that has thrust up alongside the gas company headquarters whose vast revenues are bankrolling Qatar’s US$200 billion pre-World Cup building bonanza.

Dubbed the “tower of soccer,” it is dominated by the headquarters of Qatar’s Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy — the powerful government body tasked with organizing the 2022 competition.

The men built a sleek white interior for the 38th and 39th stories, which are now occupied by some of the committee’s executives. They fitted handmade Italian furniture, bespoke etched glass paneling and a toilet that washes and dries and has a heated seat.

They were supposed to be on modest wages — about £150 a month, according to the terms with their employer, Lee Trading and Contracting — but have not been paid for months of labor — in some cases more than a year. They are sliding deeper into poverty. Families back home have taken out high-interest loans to survive.

At nightfall, Ram and the others finish their current black-market £0.50-an-hour jobs, but instead of returning to one of the labor camps where most of Qatar’s 1.4 million migrant workers live, their minibus turns into a street of villas, an area where migrant workers are banned from living. This is their secret lodging house, where they have been trying to avoid detection by the Qatari police since Lee Trading collapsed and left them without vital permits.

Thirty-two men are squeezed into cockroach-infested bedrooms that are crammed with bunkbeds screened off only by towels. Food is kept in grout tubs on the floor. After they have cooked, they slump on to thin, dirty mattresses and explain how Qatar’s World Cup dream has turned them into victims of a kind of modern-day slavery.

Ram, 26, from Nepal, says he has been to the labor court about 15 times in a vain attempt to get their missing money. Each time, it costs two days’ wages to get there and back, but there has been no progress. He cannot afford to travel to the court and is ready to give up.

“We are in very big trouble, so I want to say to workers not to repeat our mistakes,” he says. “The government, the company: Just provide the money. I am not angry with the spending of money by Qatar to bring the World Cup, but we just expect our salary.”

Krishna, also from Nepal, has not been paid for any work on the al-Bidda project for more than a year.

“I feel very bad about it, but that’s obvious,” he says. “I was working very hard, but at the end of the day I didn’t get anything. Now we work illegally. It is very dangerous. If the CID [Criminal Investigation Department] come and we have no ID, then they put us in jail.”

This has already happened to five of his colleagues. He says some workers are owed 11 months’ salary, others 13 months’ and adds that there has been no official help for them.

Qatar’s prime minister was specifically told about their plight in December, when Amnesty International complained about the al-Bidda workers’ situation, but nothing has happened.

A statement from Qatar’s 2022 World Cup organizing committee says it did not commission Lee Trading and has been using the offices temporarily.

It says it is “heavily dismayed to learn of the behavior of Lee Trading with regard to the timely payment of its workers” and “will continue to press for a speedy and fair conclusion to all cases.”

Unlike almost anywhere else in the world, the workers cannot legally take their labor anywhere else without permission from their employer. Their passports have been taken from them and in any event, under the kafala system of labor sponsorship, they can only leave the country with the permission of their employer or sponsor.

This was not just any project. Contract documents obtained by the Guardian show the building fit-out was commissioned by Katara Projects, a Qatari state entity under the auspices of the then-heir apparent, Sheik Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani, who is now emir.

The project director was Hilal Jeham al-Kuwari, the president of the Aspire Zone Foundation, the royal family’s elite sports foundation, and also chairman of Katara.

A spokesman for Aspire said the offices were intended for Katara.

“I went on-site once and they didn’t even have water and they were working in 55°C heat because there was no air-conditioning,” a western source says. “My pay was delayed at one point and they did something about it because I was a westerner.”

In November last year, Amnesty raised the case in person with the prime minister and interior minister of Qatar and wrote to the Ministry of Labor, asking officials to ensure the men received the salaries they were due, and to allow them to leave Qatar or find new jobs.

“It is deeply depressing that these men have still not received the wages they worked for and are living in appalling conditions many months after we brought their plight to the government’s and the client’s attention,” says Amnesty researcher James Lynch. “They have seemingly been abandoned. This case highlights the deep-rooted problems with Qatar’s sponsorship system and the inability of the court system to effectively deliver justice to migrant workers.”

Katara said it terminated the agreement with Lee Trading when it found out about the mistreatment of workers and that it reported managing director Lim Ah Lee and his Qatari partner, Khalid al-Hail, to the labor ministry for nonpayment of wages.

“Every effort was made to repatriate the workers involved on the al-Bidda Tower project or transfer them to new employers. If there are employees who were not repatriated, did not find employment or did not receive compensation, we would be happy to engage in any effort with the Ministry of Labor and Ministry of Interior to rectify the situation,” it said.

The al-Bidda workers’ predicament is far from unique. Despite recent assurances by the government that it will reform its labor system and remove the power employers have over their workers, the Gulf state’s extraordinary ambition is still being enabled by the exploitation of some of the world’s poorest people.

The story repeats itself. Men from poor countries pay recruitment agents fees ranging from £300 to £2,000 for the right to be offered a job at low wages. On arrival in Qatar, they find their pay slashed, then stopped. The excuses come: The subcontractor has not been paid, the money will come by Monday — but the pay does not arrive. Employers seize passports and the only body that can issue a permit for a worker to leave Qatar is the employer himself. Changing jobs is impossible.

It is modern slavery enforced not through shackles and whips, but by fiddled contracts, missing permits and paperwork, and the Guardian has found it happening just down the road from the desert palace of Qatar’s emir, Sheik Tamim bin Khalifa Al-Thani.

The turn off the eight-lane Dukhan Highway, just 20 minutes west of the vast royal desert palace compound, into Shahaniyah Camp is a transition to a scene echoic of one of the poorest parts of South Asia. The road becomes a rocky track, street lights disappear and men in lungis weave through the shadows past rubbish-filled gullies.

This is where 25-year-old Nepalese father-of-two Ujjwal Bishwakarma lives with colleagues who work six or seven days a week building car showrooms, apartments and supermarkets.

Inside the concrete blocks, eight men sleep per room. They work for a theoretical wage of about £8 a day, but 65 of them say they have not been paid for any work they have done since January by their employer, Ibex Contracting and Trading.

Men wash in broken and filthy squat toilet cubicles. The cisterns are not connected to the water supply, bins overflow and the drinking-water filter is changed once in five months, workers say, causing stomach troubles. They cannot afford medicine and their employer has not provided medical cards granting access to free healthcare.

Ujjwal left Nepal in autumn last year, shortly before the birth of his second child, Milo, whom he has never seen. Without his remittances, his family has had to take a £660 loan at 48 percent interest a year. Every day he remains unpaid, the debt is mounting.

“There’s nobody else to look after my family, so they had to take the loan,” he says. “We have questioned [the company] time and again. In the past two months, the company keeps on extending the date of providing salaries. They have extended the date four times so far. It is not good.”

The immigration document of another worker, Shanbu, shows that he had agreed to terms with Ibex to be employed as a foreman on a basic salary of £410 a month.

However, the contract signed with the employer on his arrival was for £150 a month to work as a carpenter — a 64 percent cut. The men have been running up huge debts at the local grocery store.

“I am not happy,” Shanbu says. “My family members are asking me to come back if there is no good work and apply for other countries. I am regretting [coming] now. The money I am earning here could have been earned in Nepal.”

Reached by phone, Ibex manager Srikanth says: “My problem here is I signed a contract for 15 million [rial, US$4.1 million] and I was supposed to receive my advance during March, but it was delayed. I am expecting the payment at any moment.”

He says he will pay off their grocery debts and promises to pay the late wages within days, but when the Guardian checks later, the money has not arrived.

“As far as my company is concerned, I would never put people in this unfortunate situation, but the market condition is like this,” he says. “I cannot escape from the market.”

In recent days the Guardian has contacted him again, to be told the workers were owed three months’ salary, not five, and that two months of that have now been cleared. However, Ujjwal Bishwakarma, one of the workers, says their last payment was for April.

Srikanth says “the water for drinking and cooking has been addressed by regularly filling the water tank full of sweet water,” adding that new coolers have been provided, with double filters.

He says Ibex has started “regularizing the medical-card issues” and that in the meantime, if anybody is unwell, the firm provides treatment through a private clinic.

He will not comment on the large discrepancy in Shanbu’s wages.

However, his recruitment agent in Kathmandu, Capital International Manpower, says Shanbu is “overreacting” and that they sent him on a foreman’s contract because that was the permit supplied by Qatar.

“He is not [a] foreman, he is [a] mason,” the agency says. “He should think about his ability first and then only he can make [an] issue.”

Old Tata buses rattle along Doha’s highways as the sun goes down, taking workers on the long drive back to camp. On a bus pulling out of Lusail City, where a stadium is to be built to host the 2022 final, workers peel off headscarves and masks. Some rest their foreheads on their arms to sleep. Others fish out mobile phones and click on to Facebook or text home. Talk turns to how injury and sometimes death has become part of life on Qatar’s building sites.

Umesh Rai, a Nepalese plumber who has spent three years in Qatar, tells of several accidents, even though he says his employer provided proper safety equipment.

“Six or seven months ago, there was an accident,” he says. “Some heavy object fell down and hit a person on the ground. Another case was four months back, when scaffolding fell and hit a man’s head, smashing his helmet.”

There have been confirmed accidents involving other contractors. Midmac, a major contractor working at Lusail, says a Filipino trainee driver was crushed to death by a truck in a stock area last year.

“The truck went forward and ran over the guy,” says Clark White, the company’s health and safety manager. “From the finding of the client, everything was in place safety-wise.”

The firm has also confirmed another incident where about 17 workers were injured when a huge steel cage moved unexpectedly and trapped workers. It says the injuries were not serious.

Hamad Hospital is a high-quality facility: The main entrance evokes a five-star hotel and migrant workers get free healthcare if they have a medical card. There are 70 workers in the trauma waiting room, some unconscious or vomiting because of the heat, others with head injuries. One grimacing worker is clutching his groin.

One of the great mysteries is why so many fit young men are dying from what the hospitals call “sudden cardiac death.” In 2012 and last year, 500 men from India, Sri Lanka and Nepal died like this. Whether it is caused by exhaustion or heat remains unclear because Qatar does not routinely carry out autopsies.

Rishi Kumar Kandel, 42, flew out to Qatar from Nepal in February. Within months his coffin had arrived back at Kathmandu airport. He had died suddenly in his labor camp bed after a hot day’s work on May 23.

Kandel had borrowed money at 24 percent interest a year to pay the £500 agent costs, but by the time he died he had managed to send only £170 back home. The company that employed him says it would not pay compensation because he died of natural causes. Back in Nepal, his wife, Saraswati Kandel, is dealing with debt as well as grief.

“No one should go to Qatar,” she says. “I don’t want what has happened to me to happen to any of the other wives, sisters or mothers. Nepali workers go to Qatar to work — so [the Qatari government] should also do something for us; maybe pay back our loans and other necessary things.”

She says her husband was hardly ever paid by his employer and did not get the job or salary he was promised. He had been complaining of heat and headaches before he died. His death certificate says he died from “acute heart failure due to natural causes.”

Migrants’ daily schedule is only broken on Friday afternoons when work stops, for most at least. In Saliya, young men mill around the camps. Some dash to a makeshift mosque. Others venture into central Doha to meet old friends from home. It is also the time a secret union meets.

Unions are banned in Qatar, but in a room above a shabby Indian restaurant in Doha, 15 Nepalese workers rearrange the tables for an illegal support group meeting. Topping the agenda is the government announcement of plans to reform the labor laws — an attempt to address the appalling conditions.

“We think they are only changing the terminology and not the sponsorship system, the agent system and the situation with passports and ID cards,” one member says. “Because if they really do change the rules, it will slow down construction.”

Another says: “In fact, it is getting worse than before, because companies are anticipating the changes to the labor laws and so are making workers sign five-year instead of two-year agreements. Before, if we complete two years, we can change companies; now we have to wait five years. Only yesterday they forced me to sign a five-year contract.”

The labor ministry said last month that it had punished 200 companies in the first quarter of the year for labor law violations after inspections on 3,485 worksites targeting safety. It said it was launching a wage-protection system involving workers being paid through trackable transactions to banks or exchange houses.

However, in the same month, Qatar abstained in an International Labor Organization vote in favor of a protocol against forced labor that includes protection measures for migrant workers.

There is much evidence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is sending soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and is learning lessons for a future war against Taiwan. Until now, the CCP has claimed that they have not sent PLA personnel to support Russian aggression. On 18 April, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelinskiy announced that the CCP is supplying war supplies such as gunpowder, artillery, and weapons subcomponents to Russia. When Zelinskiy announced on 9 April that the Ukrainian Army had captured two Chinese nationals fighting with Russians on the front line with details

On a quiet lane in Taipei’s central Daan District (大安), an otherwise unremarkable high-rise is marked by a police guard and a tawdry A4 printout from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicating an “embassy area.” Keen observers would see the emblem of the Holy See, one of Taiwan’s 12 so-called “diplomatic allies.” Unlike Taipei’s other embassies and quasi-consulates, no national flag flies there, nor is there a plaque indicating what country’s embassy this is. Visitors hoping to sign a condolence book for the late Pope Francis would instead have to visit the Italian Trade Office, adjacent to Taipei 101. The death of

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), joined by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), held a protest on Saturday on Ketagalan Boulevard in Taipei. They were essentially standing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is anxious about the mass recall campaign against KMT legislators. President William Lai (賴清德) said that if the opposition parties truly wanted to fight dictatorship, they should do so in Tiananmen Square — and at the very least, refrain from groveling to Chinese officials during their visits to China, alluding to meetings between KMT members and Chinese authorities. Now that China has been defined as a foreign hostile force,