For Ou Chengbi, a butcher at a sweltering open-air market on the outskirts of Guangzhou in southeastern China, it is hard to see signs of recovery in her country’s economy. Dripping with perspiration near unrefrigerated slabs of beef in her stall, she described how as recently as last winter she could still chop up an entire cow each day and sell it all.

“Now I can only sell half a cow a day,” she said.

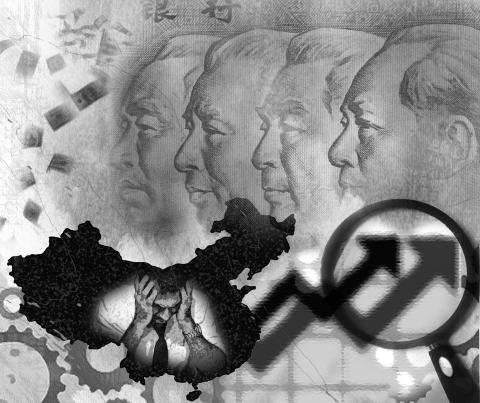

Millions of Chinese businesspeople like Ou seem to be struggling, even as data suggest growth is stabilizing.

The National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing announced on Wednesday that GDP growth edged up in the second quarter to 7.5 percent compared with a year ago. However, independent surveys of businesses across China show that in sector after sector, sales and confidence are still deteriorating.

“All of them are pointing in the opposite direction from this supposed GDP number,” said Leland Miller, president of China Beige Book International, a New York data service that surveys 2,200 private businesses across China each quarter to gauge economic activity.

One of the biggest engines of Chinese economic growth in recent years — construction and other private-sector investment — is sputtering, while exports have only begun to recover from a weak winter and retail sales growth is leveling off. That leaves government investment and spending, which are running strong, propelled by redoubled lending this spring by the state-controlled banking system to the national railroad system, local governments and state-owned enterprises.

The result has been frenzied spending on the construction of new railroad lines — up 32.1 percent last month from a year earlier — and subsidized housing. Steel output in China is setting records by tonnage as a result, even as the number of housing starts in the private sector is falling steeply.

Total lending has now risen faster than economic output, even before adjusting for inflation, in every quarter since late 2011. Lending accelerated further last month, data released on Tuesday by the People’s Bank of China showed. Yet Miller’s survey and others show that private businesses are becoming less and less interested in borrowing money, because they see few opportunities to invest it profitably.

“We have not felt any improvement in our business since the beginning of the year,” said Wan Yanhong, the business manager at the Nanchang Zerowatt Electric Appliance Co in Nanchang.

“Generally speaking, comparing recent months to the same period last year, business has been very slow and very quiet,” said Kay Lam, manager of an office furniture store in Guangzhou.

Chinese officials have repeatedly called for rebalancing the economy, encouraging more spending by households, which save nearly half their incomes, and less dependence on debt-financed investment projects. However, each time growth starts to fall below the official target of roughly 7.5 percent — as it did in the first quarter, when it was 7.4 percent — the government quickly opens the spigots for further credit.

Some economists inside and outside the government contend that China has a choice: slow down the lending and accept steady declines in economic growth each year, or continue heavy lending and risk a sharp drop in economic growth someday when the financial system begins to teeter.

“Although there is no way to predict with accuracy and certainty the point at which China will reach the limits of its debt capacity, I believe that current rates of credit expansion can continue at most for another three to four years,” Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, wrote in his newsletter after the release of the economic data.

Yet China’s economic outlook retains pockets of long-term strength. One of them is that tens of millions of Chinese workers have more money to spend each year. Wednesday’s data showed that average wages for migrant workers grew 10.6 percent this summer from a year ago. That was nearly five times the 2.3 percent rise in consumer prices over the past year.

Though migrants often have less than a high-school degree, they have fared better than more educated young people in China’s job market in recent years, as a quintupling in the number of college graduates has produced a glut in a country still heavily reliant on blue-collar sectors like construction and manufacturing.

Xu Hua, a graying, unshaven man, strained to carry a succession of very large white sacks of rice on Wednesday from a delivery van into a Guangzhou restaurant. However, he said the task paid better than it did a year ago. He and a co-worker each earned 50 yuan (US$8.10) for more than two hours of unloading the truck; they earned 40 yuan for the same job a year ago, Xu said.

“Who is willing to do this anymore?” he added.

Consumer retail sales are growing strongly, up 12.4 percent last month from a year earlier, according to government figures released on Wednesday, nearly matching a pace of 12.5 percent in May.

However, that has not been fast enough to offset the effects on the economy of a deceleration in private-sector investment, including a 14 percent drop in housing starts last month compared with a year earlier. Prices for new apartments have dropped in some cities and the number of transactions has slumped.

Most economists say Chinese households have the financial strength to step up spending faster than their incomes by reducing their prodigious savings rates. However, for revenue, the Chinese government relies heavily on steep value-added taxes that penalize consumption, while a faltering housing market has damaged confidence.

“There are fewer people even coming in to look,” said Deng Weiping, a wholesaler at a fabric market in Guangzhou. “And the people who do come in buy less than before.”

Additional reporting by Hilda Wang

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its