From the high windows of a warehouse in southern Spain a shaft of light falls on the white-gloved hand of insect farmer Laetitia Giroud. She is holding a large cricket, which sits perfectly still above the plastic box that is home to hundreds of its relatives. They are chirping to each other, giving the industrial unit a gently bucolic air. Nearby are another 30 or so boxes, filled with mealworm, black soldier flies and grasshoppers.

“They have a great life,” said Giroud, smiling at the elegantly poised insect. “They just eat and make love, eat and make love.”

Paris-born Giroud unabashedly romanticizes her charges, cooing over how “beautiful” the mealworms are and how they smell like honey. She also has the practical attitude of a farmer and looks amused when I ask how many insects she has.

“How many? I don’t know. A million? They’re not like pigs or cows. We’re planning to raise 15-20 tonnes a year,” she said.

While the world has been fascinated by Mark Post and his team’s 250,000 euro (US$330,000) attempt to make a stem cell burger at Maastricht University, there are many experts who think insects are a more likely protein source for a hungry world. In a 2011 report the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) quoted estimates that the production of 250g of lab-grown “beef” would cost in the region of US$1 million. It cited reports that said even if produced on an industrial scale, it would still cost “£3,500 [US$5,400] per tonne, approximately twice the cost of conventional unsubsidized chicken meat production in the EU.”

In contrast, Giroud and her partner Julien Foucher launched their company, Insagri, based in Coin, near Malaga, earlier this year with an investment of 24,000 euro (US$32,000). Initially, they intend to grind the larvae of black soldier flies into a high-protein dust and sell it as a replacement for fishmeal to fish farms on the Andalusian coast. In the long term, though, they are more interested in raising insects for human consumption. They already have a client in the Netherlands who, from next month, will sell their dried crickets and grasshoppers as a snack.

Potentially more significant as a rival for both meat and lab-meat is their “protein flour” — dehydrated, ground-up insects — which can be added to everything from cereal to energy bars.

“We have a client in Belgium who’s planning to make a tomato sauce and tomato puree using our mealworms as a base,” Giroud said. “It’s amazing what you can do. The market is huge. In 2020 we hope to open our first insect fast-food restaurant — like a sushi bar — in Paris or Madrid.”

The FSA appears to think “Yo! Grasshopper” is still a distant prospect, but they have already given “protein flour” a cautious welcome.

“Although whole insects may be niche products in the UK,” it wrote in 2011, “the use of purified or partially purified insect protein could have greater commercial viability, if a reliable source could be identified.”

It seems that farms like Insagri could become increasingly common. Anybody who watched the BBC documentary Can Eating Insects Save the World? or who has read any of the many recent articles extolling the virtues of entomophagy (the human consumption of insects) will not need to be told that our six-legged friends are on the march.

The idea is not new: in 1885, amateur naturalist Vincent Holt wrote a pamphlet called Why Not Eat Insects? praising slug soup and moths on toast. Of course, it is not taste that is the motivation now: as Post emphasized in his press conference, the mass consumption of meat is expensive, unhealthy and environmentally disastrous. The livestock industry is estimated to be responsible for 17 percent to 18 percent of greenhouse emissions, through production, transport and digestive gas. Insects are full of protein, have a small carbon footprint and are potentially much cheaper than both meat and lab-meat.

For Giroud and many others, the question of whether the Western world should eat insects has been settled. Economics and demographics make it all but inevitable. The question is not “why eat insects?” it is “how are we going to eat insects?” Is “protein flour” going to seem more or less disgusting than just popping a fried cricket into your mouth?

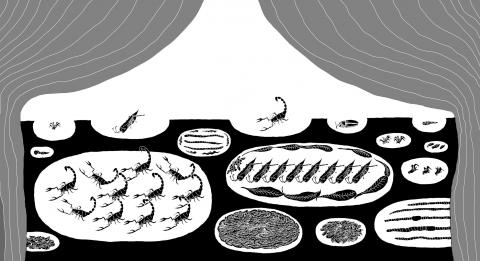

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that about 2 billion of the world’s population already eat insects as part of their normal diet. In the UK, though, we still have the idea of insect-consumption as being a grim challenge on programs such as I’m a Celebrity ... Get Me Out of Here! When you can buy them, they are often prepared in a deliberately wacky way. Fortnum & Mason, for example, sells a range of insects called “Edible” that includes ant lollipops and toffee scorpions, bought, presumably, as a joke more often than as a snack.

While green issues may be the main motivation for eating insects, the real challenge for the entomophagy evangelists is to convince westerners to choose them for their taste.

“Everyone doing insects at the moment seems to be focusing on them as a novelty,” Aran Dasan of London-based insect marketers Ento said. “Even if their intention is to popularize it, no one’s treating it like an ingredient. For example, [London restaurant] Archipelago, which specializes in exotic foods, when they serve locusts, they serve them in a salad. Seeing insects on leaves — that is where locusts live normally. It looks like they are about to jump off the plate at you. Our approach is that you never see an insect in our food. All of our food we design to be, not just delicious, but normal looking. We want it to be as unintimidating as possible.”

Ento was formed by a group of young designers while they studied at Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art. Their long-term mission includes plans for an insect restaurant and, eventually, insect ready-meals in supermarkets. They, too, are inspired by sushi.

“Sushi was one of our big case studies,” Dasan said. “It’s gone from relative obscurity to being available in Tesco in just 30 years. That’s a very fast change in food perception. What sushi does very well is that it’s fun, visually appealing and shareable because it’s bite-size. That’s what we’re going for with Ento.”

However, there is still work to be done convincing both the general public and legislators. Spain’s response to interest in edible insects was to declare insect retailers illegal. In 2008 an edible insect shop at La Boqueria market in Barcelona was closed down by public health officials.

At Insagri, Giroud wants to employ a biologist and is struggling to find anyone.

“All the biologists who specialize in entomology specialize in controlling insects — killing them!” she said. “We need someone to help us raise them.”

In the UK, the FSA’s Novel Foods Unit will assess whether “protein flour” can be sold — a process that could take up to two years. Its head, Sandy Lawrie, is not convinced insects will become a staple in the UK any time soon.

“People were concerned about horsemeat being in their food,” he said, “and I don’t think they like the idea of locusts being in there either.”

As meat prices rise, consumers may change their minds, but this is an argument insect enthusiasts are wary of pushing too hard.

“What we don’t want people to think, which has been some people’s interpretation, is that insects are just meat for people who don’t have money,” said Eduardo Galante, professor of zoology at Alicante University and an expert in entomology.

“When you look at the comments below news articles on the internet here in Spain you can see that lots of people have got the message that ‘salaries are going down, economically we’re doing really badly, and we’re going to have to eat insects.’ It’s very important how we transmit the message. I’m convinced that, if one day an important chef decides to put insects on the menu here, then from that day on people will eat insects. Somebody like Ferran Adria or [Alicante’s three-Michelin-starred chef] Quique Dacosta. At the moment eating insects, in the West, is considered something just for frikis [geeks],” he said.

Dacosta himself is unconvinced and thinks there is too much of a “cultural barrier.” However, Rene Redzepi chef and co-owner of the world’s most fashionable restaurant, Noma in Copenhagen, has regularly served insects, and his Nordic Food Lab has received 3.6 million kroner (US$640,000) from environmental charity the Velux Foundation to further its research into insect “deliciousness.”

The head of the laboratory, Ben Reade, however, is concerned by the idea of “protein flour.”

“Putting insects into nondescript chunks of protein, I hesitate to say it, but it’s very dystopian,” he said. “When you’re dealing with battery-farmed insects and turning them into chunks of protein you’re on a slippery slope. The way I see that going is massive insect farms in north Africa, where they’re grown on the cheapest land in the planet, they’re fed antibiotics before they’re even ill, they’re shipped to Europe to be turned into these nondescript chunks of protein and they’re formed into the shape of chicken breasts and then shipped back to Africa where chicken is an unaffordable luxury.”

For the Nordic Food Lab, eating insects is part of a wider move toward diversifying the food supply and going back to nature. Its most famous creation is the “chimp stick” — a whittled liquorice root, brushed with honey, and studded with fruits, seeds, crushed grains, leaves, flowers and ants. It is designed to make the point that humans are primates and we enjoy pretty much the same kind of things, including the taste of ants, as our chimpanzee cousins. Reade said it also illustrates an important point.

“I hope there can be a knock-on effect of our work, where people who have traditionally eaten these things don’t give it up,” he said. “That to me is more important than new cultures adopting insects ... that cultures who eat insects don’t start perceiving it as disgusting and moving towards highly processed beefburgers.”

It is true that the movement of Westerners towards eating insects has been dwarfed by the movement of people in the rest of the world towards meat. According to the FAO, in 1961 the Chinese consumed 3.6kg of meat per person. In 2002 that figure had increased to 52.4kg. If the world’s two billion entomophagists were to decide that insects are disgusting, there is no way of producing enough meat to feed them all. Even vegetarians will find prices of their staples rising as more land is set aside for animal feed.

The “dystopian” future of meat for the rich, insects for the poor, however, has to be better than “meat for the rich, nothing for the poor.” Either way, the mission of groups such as Ento and the Nordic Food Lab could be more important than we think. If the new question is “how do we eat insects?” or, indeed, “how do we cook lab-burgers?” then it is chefs, not biologists or chemists, who will have to lead the way.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

Liberals have wasted no time in pointing to Karol Nawrocki’s lack of qualifications for his new job as president of Poland. He has never previously held political office. He won by the narrowest of margins, with 50.9 percent of the vote. However, Nawrocki possesses the one qualification that many national populists value above all other: a taste for physical strength laced with violence. Nawrocki is a former boxer who still likes to go a few rounds. He is also such an enthusiastic soccer supporter that he reportedly got the logos of his two favorite teams — Chelsea and Lechia Gdansk —