It is summer term at Maidwell Hall prep school. The boys and girls are back from holidays. Among them, and fresh off the plane from St Petersburg, is a new Russian pupil, Gosha Nikolayev.

“I’m a bit scared and a bit excited,” Gosha said.

His father, Sergei, has come to the UK with his 11-year-old son to drop him off. If all goes well Gosha will spend two years at Maidwell Hall, before moving to a top boarding school. Dad has ruled out Eton, so this could be Charterhouse or Stowe.

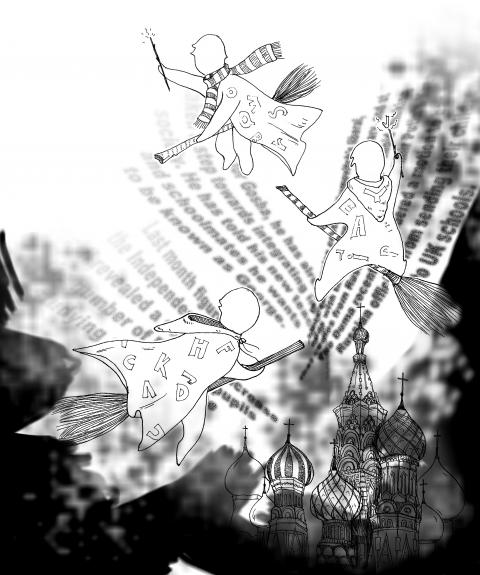

Gosha’s new school near Northampton is a vision of how foreigners must imagine the land of Harry Potter. The main building is a dreamy turreted mansion overlooking its own boating and fishing lake. Maidwell Hall’s Web site shows pupils reading on the lawn under a perfect blue sky, playing rounders or sharing a mealtime joke. The ethos is old-fashioned: boys wear tweed jackets, corduroy trousers and ties. Good manners are encouraged; mobile phones banned.

“We are trying to create a country house atmosphere,” headmaster Robert Lankester said. “It always existed in prep schools before, but has been lost in many cases.”

“Parents from abroad love the tradition. They want to buy into something British,” he said.

Gosha is the school’s second Russian; the first — “a lovely chap, loads of friends,” the headmaster said — is happily settled at Stowe.

Last month, figures from the Independent Schools Council revealed a stunning increase in the number of Russian pupils studying at UK private schools, up from 816 in 2007 (3.9 percent of all overseas pupils) to 2,150 this year (8.3 percent).

The largest number of overseas boarding students come from Hong Kong and China, followed by Germany. However, it is the Russians, in fourth place, who are the fastest-growing national group, with Britain and its private schools increasingly attractive to parents from Moscow and St Petersburg.

But why? According to Irina Shumovitch, an educational consultant who runs a placement service for Russian parents, British education has an unbeatable reputation. For the vast majority of Russians the fees are unaffordable. However, for the rising upper-middle class it remains the top choice.

Shumovitch puts this in part down to “herd mentality.”

“The myth says the best place to send your kids to school is England. The best place to ski is Courchevel and the best diamonds are de Grisogono. I welcome the myth because education here is fantastic,” she said.

Shumovitch helps Russian-speaking parents navigate their way through the entrance and exam system. She arranged tours for Sergei and Gosha to various prep schools including Maidwell Hall; Gosha also went to summer camp at Gordonstoun, Prince Charles’s alma mater. British schools nurture individuality and creativity, and teach pupils critical thinking, encouraging them to write essays and see both sides of an argument, she added.

The more rigid, fact-driven Russian system, by contrast, relies on “fear and pressure,” meted out by older, Soviet-trained teachers.

In a Russian context Shumovitch’s liberal, child-centered ideas are quietly revolutionary, and at odds with the xenophobic, often paranoid thinking that comes from Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin. The Russian Duma recently considered a motion to ban top Russian officials from sending their children to UK schools. (Deputies dismissed it, arguing that contrasting the British and Russian systems might be helpful.)

“I believe British schooling is good for Russian children and good for Russia,” Shumovitch said. “They are learning different values, and will return to Russia more aware, more tolerant and more open.”

Russia’s darkening politics has prompted growing numbers of Russian parents to send their children to Britain. Numbers are up 27.4 percent this year.

Natasha Semyonova-Bateman, who helps wealthy Russians relocate to the UK, finding homes and schools, says some of her clients are “patriotic about Russia.”

Others are opposed to the Putin regime. Both groups are united by a lack of faith in the country’s future and see a British education, and a British passport for their kids, if they can procure one, as an “exit strategy,” she said.

“They think the next generation should be out of Russia. This idea has grown in the last couple of years,” Semyonova-Bateman said.

“The atmosphere inside Russia is like [British author George] Orwell’s 1984. It’s a suffocating society. They [Russians] don’t believe in the future. They don’t trust anyone including the authorities. Parents think: It’s too late for us. We have business here. We speak Russian and we can’t change our lives dramatically, but can change it for our kids,” she added.

Official relations between London and Moscow have been largely dreadful since the 2006 polonium murder of Alexander Litvinenko. Nevertheless, many ordinary Russians are enthusiastic Anglophiles. Harry Potter — or Garry, to give the boy magician his Russian pronunciation — is extremely popular in Russia, as is the British queen. Younger members of the country’s affluent, Westernized elite speak English.

“I like the humor and the irony,” Sergei says of Britain, in perfect English, when we meet in an upscale cafe in Sloane Square, London.

“Like the Roman empire, Britain has an assimilating culture,” he said.

Educated, self-made, and casually dressed in jeans and a V-neck, Sergei grew up in a St Petersburg intelligentsia family. He studied theoretical physics, but with science in disarray in the post-Soviet 1990s, he turned his hand to business, first owning a St Petersburg radio station, then setting up a successful chain of high-end tea shops. He is now worth between £15 million and £20 million (US$23 million and US$30 million).

“We are pretty wealthy,” he said.

Does he have a yacht?

“A small one, 44 foot [13m]. I’ve been sailing with my dad since I was a boy,” he said.

During a recent recce to London, Sergei says he bumped into two friends from St Petersburg on the same flight who were also looking at schools for their children and a flat in London. Sergei says he has no plans to leave Russia — “you can live partly here, and partly there,” he points out — but hopes Gosha will emerge from the UK with an international education.

And a normal childhood: “We don’t want him to be spoiled,” he said.

This is understandable. Back in Moscow the super-rich travel with armed bodyguards and live in fortress-like mansions.

For some Russian parents the merit-based British system is a bit of a shock. There are stories — not apocryphal, I am told — of prospective parents trying to bribe headmasters with bags of cash.

In fact, there is a more respectable route to bump your child’s application up the list, with most private schools running a “development fund.”

One Russian father got his son into a leading private school after making a large donation; however, his second, less academically able son was turned down.

Most Russian children adjust well to their new environment; they rapidly absorb Britain’s jokey, understated culture, where showing off how rich you are is regarded as vulgar. The son of one well-known Russian oligarch, according to Shumovitch, switches phones when he returns to his boarding school after the holiday break. (He hides his Vertu and swaps it for a battered Nokia.) Others adopt British upper-class sartorial habits: they buy shirts from Jermyn Street, shoes from John Lobb.

A minority of Russian kids struggle. One observer describes the scene at the Lanesborough hotel in London, where a Russian mum with KGB connections had taken her 12-year-old son at a British prep school out for breakfast. The boy waved away his egg twice, complaining that it was not done the way he liked it. The mother was delighted with his behavior, reading it as a sign of his assertiveness.

“Some parents think Eton is Dolce & Gabbana,” the source said.

Graceless or not, the influx of Russian students is a boon for British boarding schools, amid the UK’s recession. Stowe, Charterhouse, Wellington College and Shrewsbury accept large numbers of Russians. Lankester said he tries to limit overseas numbers so as not to dilute the “British cultural experience.”

“I think there is a downside to having too many [pupils] from one country. Russians are an attractive prospect for schools that have places, but families don’t want lots and lots of Russians in the year group,” he said.

Generally speaking, Russians seek out schools within easy reach of Heathrow airport. Those in London and between there and Oxford are prized. Shumovitch tries to persuade her Russian clients to bring their children to the UK as early as possible, to immerse themselves in the British system and to improve their English.

The competition for places at top senior schools is intense, she said.

“Eton is now highly academic. You have to have very high grades and do common entrance. It’s almost impossible for a Russian child at 13 to get from Moscow to Eton because of insufficient English, no matter how bright the kid is,” she said.

As for Gosha, he has already taken a step towards integrating into British society. He has told his new teachers and schoolmates he wants to be known as George.

Taiwan has lost Trump. Or so a former State Department official and lobbyist would have us believe. Writing for online outlet Domino Theory in an article titled “How Taiwan lost Trump,” Christian Whiton provides a litany of reasons that the William Lai (賴清德) and Donald Trump administrations have supposedly fallen out — and it’s all Lai’s fault. Although many of Whiton’s claims are misleading or ill-informed, the article is helpfully, if unintentionally, revealing of a key aspect of the MAGA worldview. Whiton complains of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s “inability to understand and relate to the New Right in America.” Many

US lobbyist Christian Whiton has published an update to his article, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” discussed on the editorial page on Sunday. His new article, titled “What Taiwan Should Do” refers to the three articles published in the Taipei Times, saying that none had offered a solution to the problems he identified. That is fair. The articles pushed back on points Whiton made that were felt partisan, misdirected or uninformed; in this response, he offers solutions of his own. While many are on point and he would find no disagreement here, the nuances of the political and historical complexities in

Taiwan faces an image challenge even among its allies, as it must constantly counter falsehoods and misrepresentations spread by its more powerful neighbor, the People’s Republic of China (PRC). While Taiwan refrains from disparaging its troublesome neighbor to other countries, the PRC is working not only to forge a narrative about itself, its intentions and value to the international community, but is also spreading lies about Taiwan. Governments, parliamentary groups and civil societies worldwide are caught in this narrative tug-of-war, each responding in their own way. National governments have the power to push back against what they know to be

Taiwan is to hold a referendum on Saturday next week to decide whether the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant, which was shut down in May after 40 years of service, should restart operations for as long as another 20 years. The referendum was proposed by the opposition Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and passed in the legislature with support from the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). Its question reads: “Do you agree that the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant should continue operations upon approval by the competent authority and confirmation that there are no safety concerns?” Supporters of the proposal argue that nuclear power