The euro, many now believe, will not survive a failed political class in Greece or escalating levels of unemployment in Spain: Just wait another few months, they say, the EU’s irresistible collapse has started.

Dark prophecies are often wrong, but they might also become self-fulfilling. Let’s be honest: Playing Cassandra nowadays is not only tempting in a media world where “good news is no news”; it actually seems more justified than ever. For the EU, the situation has never appeared more serious.

It is precisely at this critical moment that it is essential to re-inject hope and, above all, common sense into the equation. So here are 10 good reasons to believe in Europe — 10 rational arguments to convince pessimistic analysts and worried investors alike that it is highly premature to bury the euro and the EU altogether.

The first reason for hope is that statesmanship is returning to Europe, even if in homeopathic doses. It is too early to predict the impact of Francois Hollande’s election as president of France. However, in Italy, one man, Prime Minister Mario Monti, is already making a difference.

Of course, no one elected Monti and his position is fragile and already contested, but there is a positive near-consensus that has allowed him to launch long-overdue structural reforms. It is too early to say how long this consensus will last and what changes it will bring. However, Italy, a country that under former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s cavalier rule was a source of despair, has turned into a source of real, if fragile, optimism.

A second reason to believe in Europe is that with statesmanship comes progress in governance. Monti and Hollande have both appointed women to key ministerial positions. Marginalized for so long, women bring an appetite for success that will benefit Europe.

Third, European public opinion has, at last, fully comprehended the gravity of the crisis. Nothing could be further from the truth than the claim that Europe and Europeans, with the possible exception of the Greeks, are in denial. Without lucidity born of despair, Monti would never have come to power in Italy.

In France, too, citizens have no illusions. Their vote for Hollande was a vote against former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, not against austerity. They are convinced, according to recently published public opinion polls, that their new president will not keep some of his “untenable promises” and they seem to accept this as inevitable.

The fourth reason for hope is linked to Europe’s creativity. Europe is not condemned to be a museum of its own past. Tourism is important, of course, and from that standpoint Europe’s diversity is a unique source of attractiveness. This diversity is also a source of inventiveness. From German cars to French luxury goods, European industrial competitiveness should not be underestimated.

The moment when Europe truly believes in itself, the way Germany does, and combines strategic long-term planning with well-allocated research and development investments, will make all the difference. Indeed, in certain key fields, Europe possesses a globally recognized tradition of excellence linked to a very deep culture of quality.

The fifth source of optimism is slightly paradoxical. Nationalist excesses have tended to lead Europe to catastrophic wars. However, the return of nationalist sentiment within Europe today creates a sense of emulation and competition, which proved instrumental in the rise of Asia yesterday.

Koreans, Chinese and Taiwanese wanted to do as well as Japan. In the same way, the moment will soon come when the French want to do as well as Germany.

The sixth reason is linked to the very nature of Europe’s political system. Former British prime minister Winston Churchill’s famous adage that democracy is the worst political system, with the exception of all the others, has been borne out across the continent. More than 80 percent of French citizens voted in the presidential election. Watching on their televisions the solemn, dignified, peaceful and transparent transfer of power from the president they had defeated to the president they had elected, French citizens could only feel good about themselves and privileged to live in a democratic state. Europeans might be confused, inefficient and slow to take decisions, but democracy still constitutes a wall of stability against economic and other uncertainties.

The seventh reason to believe in Europe is linked to the universalism of its message and languages. Few people dream of becoming Chinese, or of learning its various languages other than Mandarin. By contrast, English, Spanish, French and, increasingly, German transcend national boundaries.

Beyond universalism comes the eighth factor supporting the EU’s survival: multiculturalism. It is a disputed model, but multiculturalism is more a source of strength than of weakness. The continent’s fusion of culture makes its people richer rather than poorer.

The ninth reason for hope stems from the EU’s new and upcoming members. Poland, a country that belongs to “New Europe,” is repaying the EU with a legitimacy that it had gained from Europe during its post-communist transition. The entrance of Croatia, followed by Montenegro and a few other Balkan countries, could compensate for the departure of Greece (should it come to that for the Greeks).

Finally, and most important, Europe and the world have no better alternative. The Greek crisis may be forcing Europe to move towards greater integration, with or without Greece. The German philosopher Jurgen Habermas speaks of a “transformational reality” — a complex word for a simple reality: Divided we fall, whereas united, in our own complex manner, we might strive for “greatness” in the best sense.

Investors, of course, are hedging their bets. Having ventured successfully into emerging non-democratic countries whose frailty they are starting to fear, some, out of prudence, are starting to rediscover Europe.

They might well be the wise ones.

Dominique Moisi is the founder of the French Institute of International Affairs and a professor at the Institute d’Etudes Politiques in Paris.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

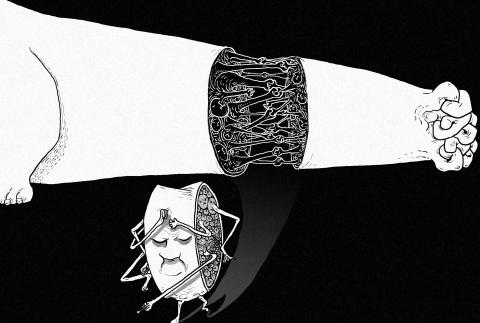

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its