In a month-long standoff between China and the Philippines over a disputed shoal in the South China Sea, Beijing has so far refrained from sending warships from its increasingly powerful and modern navy to enforce its territorial claims.

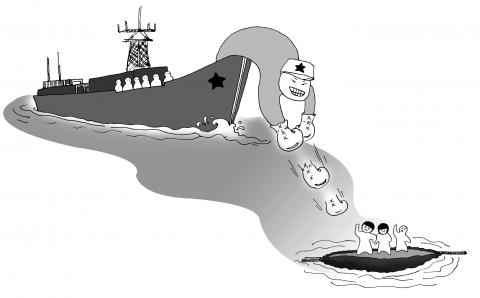

Instead, China has deployed patrol vessels from its expanding fleet of paramilitary ships to the Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island, 黃岩島), which is also claimed by Taiwan. Naval experts say the intent is to minimize the risk of conflict and contain any regional backlash.

After alarming some of its neighbors in recent years with assertive behavior in the South China Sea, China has turned to “small stick” diplomacy, using unarmed or lightly armed patrol boats from fisheries, marine surveillance and other civilian agencies, rather than warships.

Shen Dingli (沈丁立), a security expert at Shanghai’s Fudan University, said the role of these vessels was to demonstrate “soft power” and avoid the impression that China was engaged in gunboat diplomacy.

“Therefore, it is more peaceful and moral,” he said.

However, Beijing has shown no sign of compromise in a standoff that began when Chinese civilian patrol vessels last month intervened to stop the Philippines from arresting Chinese fishermen working in the disputed area. More such incidents are likely, unless the Philippines can provide a counterweight to the challenge, either on its own or with allies, security analysts say.

China’s tough stance comes at a time of spectacular political scandal and swirling rumors of high-level infighting over the sacking of the once high-flying Chongqing Chinese Communist Party (CCP) boss Bo Xilai (薄熙來).

Political analysts say the CCP will be anxious to show that it is has the unity and strength to defend any challenge to the country’s territory ahead of the once-in-a-decade leadership change later this year.

Senior leaders vying for top positions will also be keen to shore up their nationalist credentials with the politically powerful military.

Claiming sovereignty over the group of rocks, reefs and small islands about 220km from the Philippines, patrol vessels and fishing boats from China and the Philippines have been deployed to the area in an increasingly acrimonious confrontation.

The Chinese Ministry of National Defense last week took the unusual step of denying reports it was preparing for war, but the People’s Liberation Army Daily, the military’s mouthpiece, warned that the Philippines was making “serious mistakes” in maintaining its claim.

“We want to say that anyone’s attempt to take away China’s sovereignty over Huangyan Island will not be allowed by the Chinese government, people and armed forces,” it said.

Manila has called for the UN’s International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea to rule on the dispute in the strategically important and resource-rich sea. Half the world’s merchant-fleet tonnage sails across the sea and around these islets each year, carrying US$5 trillion worth of trade.

While Beijing has thus far kept its navy at a distance, the Philippines, like most regional nations, is well aware it would be overwhelmingly outgunned by China’s powerful military if it came to a fight.

After more than two decades of double-digit increases in defense spending, China has an expanding fleet of advanced warships, submarines — now the largest in Asia — and long-range strike aircraft.

However, if Beijing resorts to force, it would almost certainly drive other claimants to territory in the South China Sea — including Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia — closer together. Those three countries, along with the Philippines, are members of the ASEAN, which is creating an EU-style community that also envisions joint security.

Regional nations have also begun to cement closer military ties with the US. Starting with a trip late last year, US President Barack Obama has touted a “pivot” toward the economically dynamic Asia-Pacific region in an effort to reassure nervous allies of the US’ commitment as China flexes its economic and military muscle.

That means China will likely continue to send a strong message with its civilian patrol boats while keeping its real firepower in reserve, according to security experts.

“It is much easier for paramilitary vessels to assert sovereignty claims with less probability of escalation to armed violence,” said Christian Le Miere, a maritime security researcher at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

“It allows for more containable events and incidents,” he said.

Other Asian nations have also been expanding their paramilitary fleets in recent years, particularly Japan, which has a powerful coast guard. China’s use of these vessels, however, is drawing the most attention.

An early indication of the effectiveness of this strategy was China’s sustained harassment in early 2009 of the US spy ship Impeccable in the South China Sea off Hainan Island.

Chinese patrol boats and surveillance ships buzzed and tormented the Impeccable for days, at one point even attempting to grapple its underwater sonar array used to identify and track submarines.

“If China had deployed naval ships, the response of the US might have been more aggressive,” said Le Miere, who has studied the use of paramilitary ships in Asia.

For China, devoting more resources to these forces fills an important gap in its maritime power, between its massive merchant fleet and its expanding, blue water navy.

Chinese maritime specialists have called on Beijing to devote more attention to the civilian agencies responsible for enforcing domestic law and maintaining order in its territorial waters.

The main Chinese government agencies that deploy patrol vessels in the South China Sea and other coastal waters are the Maritime Safety Administration, the Maritime Police of the Border Control Department, the Fisheries Law Enforcement Command, the General Administration of Customs and the State Oceanographic Administration.

Other, smaller agencies, including provincial governments, local police and customs, also send patrol boats and surveillance vessels to sea.

The paramilitaries that China has sent to the Scarborough Shoal include the 1,300-tonne Haijian 75 and 1,740-tonne Haijian 84, advanced surveillance vessels from the State Oceanographic Administration.

Beijing also stationed the 2,580-tonne Yuzheng-310, its most advanced fisheries law enforcement vessel, off the disputed shoal.

Some Chinese and foreign experts have criticized the disjointed coordination of these forces.

Outspoken People’s Liberation Army strategist, Major General Luo Yuan (羅援), in March called for China to establish a unified coast guard, similar to those of Japan, the US and Russia.

In an interview with state-controlled media, Luo said up to nine agencies were now responsible for enforcing maritime law, which sometimes led to waste and inefficiency.

“If China integrated these forces, it could act more flexibly when maritime incidents occur,” he said.

As tension mounted at the Scarborough Shoal, the Brussels-based International Crisis Group warned in a report late last month that China’s poorly coordinated and sometimes competing civilian agencies were inflaming frictions over disputed territory.

“Any future solution to the South China Sea dispute needs to address the problem of China’s mix of diverse actors and construct a coherent and centralized maritime policy and law enforcement strategy,” it said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its