Totnes is an ancient market town on the mouth of the river Dart in Devon, England, It has the well-preserved shell of a motte-and-bailey castle, an Elizabethan butterwalk and a steep high street featuring many charming gift shops. All of which makes it catnip to tourists. A person might initially be lulled into the belief that this was somewhere with as much cultural punch as, say, Winchester.

Bubbling below the surface, however, is a subversive hub of alternative living, a legacy of the radical goings-on from Dartington Hall, just down the road, where Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst’s vision of a rural utopia gathered steam in the 1920s. Indeed, there are more new age “characters” than you can shake a rain stick at, more alternative-therapy practitioners per square centimeter than anywhere else in the UK and the town was once named “capital of new age chic” by Time magazine.

My family moved here when I was 10. A child of relentlessly suburban mindset, I found the town’s granola outlook unsettling. I balked at the indigenous footwear worn by Totnesians — multicolored pieces of hand-stitched leather called “conkers” — and longed for a world where it was not atypical to own a TV and talk about Dallas rather than nuclear disarmament.

My fear growing up in this neck of the woods was that people would continue to get even weirder. So it was probably just as well that I had left when Rob Hopkins arrived in 2005 and let loose the Great Unleashing, aka the launch of Transition Town Totnes (TTT).

Six years on, the Transition initiative, which attempts to provide a blueprint for communities to enable them to make the change from a life dependent on oil to one that functions without, seems to me one of the most viable and sensible plans we have for modern society. I write this on the day it is announced that the UK economy shrank by a “shock” 0.5 percent in the last quarter of last year. Everyone is blaming the weather. Hopkins isn’t. Neither is he particularly shocked.

“I think the unraveling of the debt bubble has only really started,” he said. “Up until 2008 it was all about a growing economy and cheap energy. Then we had expensive energy plus economic growth, then we had cheap energy and economic contraction. So the next phase is volatile energy and economic contraction. It’s not rocket science.”

Hopkins was in Kinsale, Ireland, working as a teacher of permaculture — a sustainable, design-based horticultural technique where growing systems mimic the ecology of the natural world — and establishing an eco village, when he attended a lecture on “peak oil” in 2004. It was his Damascene moment.

According to theorists such as Richard Heinberg, whose tome The Party’s Over charts life without oil, we have passed the point at which oil supplies peak (that was back in May 2005). From there on in oil production declines and we attempt ever more audacious land grabs to get it.

However, oil remains the lifeblood of our economy and lifestyle. What happens when the oil runs out or is disrupted? In 2000 UK truck drivers brought the UK’s food chain to its knees by blockading oil terminals. At the height of the protest the UK was 72 hours away from running out of food. If there were scant emergency measures in place, there was absolutely no vision of a life after oil.

Hopkins began to see how dependent he was on his car, to ferry his kids around and get to work. As a constructive response he began to develop an Energy Descent Action Plan for Kinsale with his students. They looked for historical examples of when the area had been more robust, more resilient to shock changes, such as when it had possessed a more localized food system. The plan split life up into categories — energy, food, transport, homes — all of which had their own solutions.

Critically, it dealt with practical considerations — for example, how much well managed woodland would it take to heat a town?

Central to the whole plan was the idea that permaculture gardening could be scaled up to bring food resilience to town centers. It offered Plan B, because Plan A was doomed to failure.

In search of a town big enough for the plan to have a wider effect, Hopkins moved back to Totnes, with its population of 23,000, with his wife Emma and their four children, and he worked on a version of the Energy Descent Action Plan with local resident Naresh Giangrande.

“After I’d been involved in Kinsale I wanted to live somewhere where there were examples of a more resilient community already up and running, pieces of the jigsaw such as a good local food system, so that people could envisage how we could develop a community,” he said.

Ben Brangwyn, a relatively recent arrival to Totnes who was to become cofounder of the Transition Network was sold on the idea as soon as he heard Hopkins giving a lecture.

“It was pretty clear to me, having studied re-localization efforts around the world, that what Rob and his students had developed in Kinsale was pretty much the smartest bottom-up response to climate change and peak oil that we had seen,” Brangwyn said.

He wasn’t the only person that thought so. Word that there was a man with an actual plan had spread fast and Hopkins was deluged by interest from all over the world. It was clear his ideas needed to be worked up into a more formal movement.

“The leap of brilliance in the energy plan was the idea that you can segregate responses to these pressures into energy, food, education, use of transport, local economics, etc,” Brangwyn said. “That’s one of the secrets of transition: Anybody who has a passion can find a place.”

“It’s not my movement,” Hopkins said, clearly uncomfortable at being portrayed as the face of the Transition Towns movement.

“We’re not Coca-Cola, we don’t send out a franchise model. It’s up to individual communities to interpret Transition however it works best,” he said.

The Transition movement works on the basis that if we wait for government to act on issues such as climate change we’ll be waiting until hell freezes over; and if we only act as individuals, that’s too little. So it’s working together as communities where the real change will happen. In offices on that steep Totnes high street, squeezed between the pet shop and a travel agency, Transition Town Totnes was formed, swiftly followed by the Transition Network, to support the growth of the movement outside Totnes.

There are now more than 350 Transition movements, 200 of them in the UK. Last month the first Australian region, Sunshine Coast, became an official Transition Town. Hundreds more communities are mulling over the idea of embracing Transition (they are known as mullers). While there has been some debate among greens as to whether Transitioners are right to put so much emphasis on peak oil, and whether climate change should really be the main driver for change, it is clear that the strategy laid out in the latest Energy Descent Action Plan is one that will protect communities in the event of both oil shocks and climate change (and possibly economic shocks, too). It certainly beats stockpiling tinned food and buying a firearm.

As I leaf through the neat action plan, it brings order to apocalyptic scenarios and creates a vision of how Transition Town Totnes could be in 2030. Some strategies are niche, but some strategies are the stuff of market-town revolution.

George Heath ran a flourishing market garden in the 1920s; his son inherited the business, opening a shop on the high street to sell the local, fresh produce. Today David Heath, his grandson, shows me the site of the market garden and large urban greenhouse in the center of town. Since 1981 it’s functioned as one of the town’s main car parks. The Transition plan is to convert it back to a market garden by 2030. How close is the town to realizing its alternative narrative?

“We did have a German visitor who was very disappointed,” Brangwyn said, “because there were still cars in the town and there were no goats on the roof.”

Totnes hosts an increasing number of Transition pilgrims who want to see what’s going on.

“People have different expectations. We’re not going to make big visual changes overnight. Transition is ground up, it’s about people doing the work for themselves. So the culture has to change first,” Brangwyn said.

I look for visual signs of change regardless. Walking through town, the most obvious is the 74 photovoltaic panels on the roof of the civic hall. I wander down an alleyway in the center of town to observe some gardens belonging to householders who were previously too busy or lacking the green fingers to make them productive. They are now little engines of town-center production, part of the Transition Network’s garden-share scheme run by Lou Brown.

“I began the project because I spent a long time in rented accommodation wandering around the town with my husband, coveting bits of garden,” Brown said. “We have up to 30 gardeners across 16 gardens producing a lot of food. A quarter to a fifth generally goes to the garden owner. Kale, flowers, beetroot, you name it, it gets grown. Obviously this is great for developing local food resistance, particularly because we have a shortage of allotments [publicly owned vegetable gardens available for rent] in Totnes and a big waiting list. The allotment society is trying to find new land all the time, and the garden share is like a seedbed for some growers while they are waiting.”

I find resident Steve Paul delighted with his 10 1.85kW photovoltaic panels, bought through Transition’s Street Scheme.

“I’ve already avoided 0.55lb [249g] of carbon this morning,” he said, checking the monitor.

One notable aspect of Transition Town Totnes is that you find renewables on perfectly normal housing. Last year the Transition Street Programme was one of 20 projects to win funding from the Department of Energy and Climate Change. It invited streets to get together to change behavior, improve energy efficiency and then to install renewable energy systems.

What’s more it provided quantifiable data: More than 500 households became part of the scheme, 70 percent were households on a limited income, and every household cut their carbon by an average of 1.2 tonnes, saving £600 (US$965) a year.

Not everything has gone as swimmingly. A local currency is central to the Transition plan.

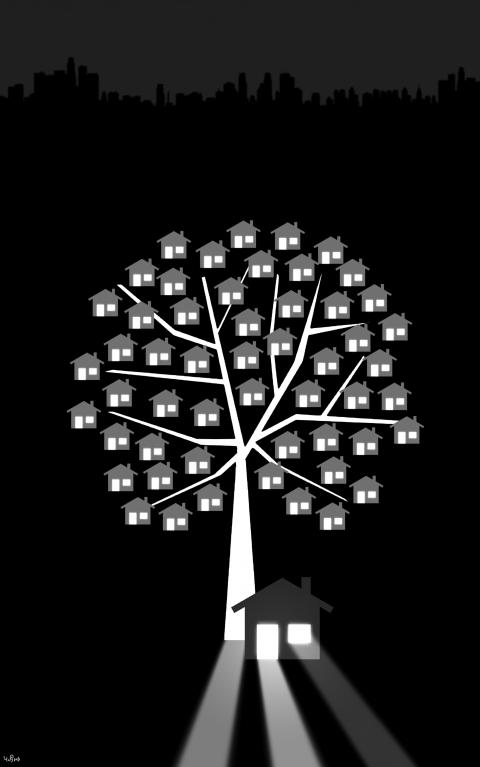

“Think of a leaky bucket,” Brangwyn said. “Any time we spend money with a business that’s got more links outside the community than in it, we leak money from the local economy. What local currency does is allow that wealth to bounce around in that bucket. We’ve barely touched the surface of systems that will benefit the local economy. We don’t just need our own pound note, but a credit union, electronic means of transaction, a time bank.”

And although you can detect a certain fondness for the Totnes pound note on the local high street, it hasn’t been as successful as Transition currency in Lewes (south of London), Brixton (in south London) and Stroud (in the west of England). There’s still work to be done.

However, Hopkins reckons TTT is still ahead of schedule.

“When I wrote The Transition Handbook [published in 2008] I was working up to the Energy Descent Plan, a sort of blueprint for the development of any community. But we did that in Totnes a year ago. So strictly speaking we’ve finished and we can pack up and go home feeling good about ourselves. But that was just the beginning. The aim of Transition is to try to relocalize the economy where it’s happening, and be a catalyst for that process of intentional relocalization,” he said.

There is a fine line between making residents aware of initiatives such as the Transition Street Project and haranguing them until they sign up.

Transitioners seem of the opinion that the latter would be fruitless; the drive needs to come from the community to join up. So at the moment it is perfectly possible to visit Totnes and not be aware it’s a Transition Town at all.

However, that will inevitably change. Local councilors already report that when they introduce themselves at national conferences and say “from Totnes,” other delegates comment, “Ah, Transition Town Totnes.” Word is spreading.

Hopkins is keen to stress that this is very different to British Prime Minister David Cameron’s interpretation of localism, devolving power from central government.

“It doesn’t mean putting a big fence up around Totnes and not letting anything in or out. It doesn’t mean Totnes will be making its own laptops and frying pans. But it means in terms of food, building materials, a lot more of that can be done locally. Which in turn makes the place much more resilient to shocks from the outside,” he said.

The great plan in Totnes included the planting of 186 hybrid nut trees around town. You can just walk around and help yourself to free nuts, which can only help community cohesion.

However, John Crisp, a local farmer who in his spare time leads Transition Town’s new Food Hub project, is keen to point out that the vision extends beyond nuts and that, come April, Totnesians will be able to order their weekly shop online and collect it on a Saturday from the local school.

“This is an initiative that connects local farmers to Transition, automatically engaging us with the farming community, of which I am one. And consumers get to buy local produce at prices comparable to those at the supermarket. Our overheads are so small that while shops and supermarkets charge a 30-40 percent mark up, we’ll be at 10 percent. Meanwhile we give producers a fair return for their produce — more than they would get anywhere else,” Crisp said.

More change is coming. Totnes Renewable Energy Society, an offshoot of TTT, has two applications in for wind turbines on nearby Kingsbridge hill and recently issued shares so Totnesians will be able to power-down, saving their own energy. And the TTT has designs on the old Dairy Crest building near the station as part of its bid to get more assets into community ownership.

When these totemic Transition symbols are up, they should invite the German guy back.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

Liberals have wasted no time in pointing to Karol Nawrocki’s lack of qualifications for his new job as president of Poland. He has never previously held political office. He won by the narrowest of margins, with 50.9 percent of the vote. However, Nawrocki possesses the one qualification that many national populists value above all other: a taste for physical strength laced with violence. Nawrocki is a former boxer who still likes to go a few rounds. He is also such an enthusiastic soccer supporter that he reportedly got the logos of his two favorite teams — Chelsea and Lechia Gdansk —