The modern pursuit of money in this territory of gleaming office towers and rural villages has long coexisted amicably with an embrace of ancient beliefs. Even a major brokerage firm issues an annual financial forecast based, lightheartedly, on the Chinese horoscope.

However, recent events have fueled fears that greed may be debasing the practice of feng shui, the Chinese system of geomancy by which the auspicious positioning of objects is believed to ensure harmony, health and fortune.

Some practitioners, worried that their profession may be falling into disrepute, recently formed a trade association that they hope will uphold high standards and provide confidence for the public.

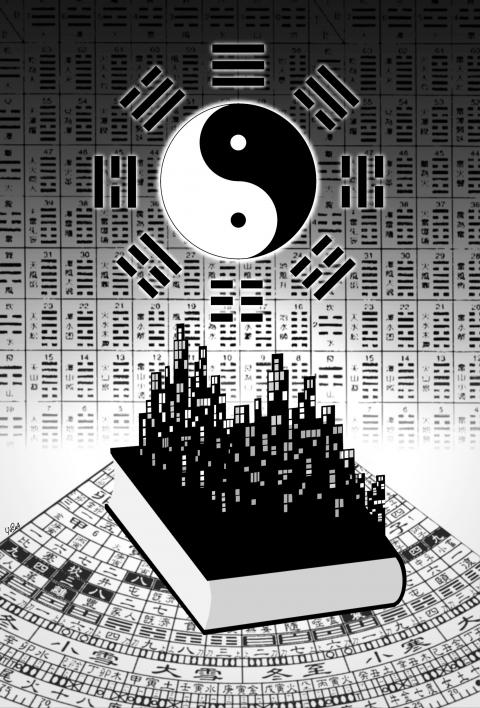

Illustration: Yusha

Over the past year, a Hong Kong courtroom drama has been calling attention to the sort of ties between money and feng shui that underlie such concerns. Tony Chan (陳振聰), 51, a former bartender turned self-proclaimed feng shui master, is appealing a court decision rejecting his claim to the fortune of Nina Wang (龔如心), one of Asia’s wealthiest women when she died in 2007 at the age of 69.

Chan contends he was Wang’s longtime lover and spiritual adviser, and is the rightful heir to her estate. His critics have accused him of forging the will and using Wang’s belief in feng shui to isolate and delude her.

In addition, some people have called for investigations into how much of taxpayers’ money the Hong Kong government has been spending to accommodate feng shui adherents.

Villages are entitled to ask the government to pay to repair any adverse changes to the landscape that were caused by development. That covers not just environmental damage, but also the possibility that ill fortune was brought on by tearing down a tree or placing a road in a way that might disturb the local qi, the energy that some Chinese believe pervades all things. Qi is a crucial factor in determining feng shui.

Requested repairs to restore positive feng shui can involve construction, like building a pavilion, or, according to the Hong Kong Lands Department, they could take the form of rituals to “drive away evil spirits and appease the gods.”

Last year, a local group challenged a village chief’s claims for feng shui compensation tied to the planned construction of a high-speed rail line to connect Hong Kong and Guangzhou. The group, representing residents of the village of Kap Lung, said the chief’s feng shui complaint was fraudulent, contending that he stood to gain financially from his request that a footbridge into the village be widened.

The chief’s company owns multiple plots of land in the area and a widened bridge to allow vehicles could make those properties more valuable, said Eddie Tse Sai-kit, a spokesman for the group, called the League of Rural-Government Collusion Monitoring.

“We want a transparent feng shui compensation system,” Tse said.

The government said in October that about US$1.2 million had been disbursed to villages since 2000 to conduct rituals to restore feng shui, but the South China Morning Post reported that the actual amount was US$72 million.

“Let’s be honest about it,” Roger Nissim, a former assistant director of lands for the government, said on a radio talk show. “Sometimes feng shui is misused and used as a lever for inappropriate amounts of compensation, and the administration has got to be aware of when it is being bluffed.”

“I believe the government treats feng shui compensation very carefully, but it is totally unacceptable that we do not know how much has been spent or what the policies are,” Hong Kong Legislative Councilor Tanya Chan (陳淑莊) said,

No one knows how many people in Hong Kong abide by the tenets of feng shui. Ho Pui-yin (何佩然), a history professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said some people might be embarrassed to acknowledge following feng shui principles.

Still, Ho points to the popularity of celebrity feng shui consultants in newspaper columns and on television shows. She speculated that as many as half of the nearly 7 million people in Hong Kong at least casually follow feng shui beliefs.

Kerby Kuek (郭翹峰), who calls himself a feng shui master, said experts in the field could charge US$400 to US$40,000 to assess a small apartment of about 55m2, depending on the fame of the consultant. Louis Wong, who teaches feng shui, said classes could cost students about US$250 an hour.

It is not surprising, then, that so many people want to learn feng shui and teach it to others, Ho said.

Such temptations are what spurred one group of feng shui masters to form the International Taoist Feng Shui and Metaphysics Association last month. They hope to restore the reputation of a profession that they worry is increasingly viewed as fraudulent. The association’s founders said it would offer courses to the public as well as a quality rating system for feng shui masters.

Some feng shui teachers in Hong Kong are not convinced that the association will do more than serve the financial interests of the organizers, rather than enhance the reputation of an ancient belief system.

“I agree with the idea of some organization to regulate feng shui in Hong Kong,” Wong said. “But maybe this is a job for the government, and should not be left to individuals.”

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India