One of the more arresting passages in British Prime Minister David Cameron’s speech to the recent Conservative party conference — a paragraph that would have prompted some reluctant nodding among left--leaning types — was this: “Citizenship isn’t a transaction in which you put your taxes in and get your services out. It’s a relationship.” It sounded great, utterly in tune with the widespread yearning for a politics about more than the bottom line, one that measures the value of life in more than pounds, shillings and pence.

The trouble is, it didn’t last so much as a week. Six days after Cameron sat down in Birmingham, the coalition set out its plans for higher education. They show just how “transactional” this government’s view of citizenship really is: that it boils down to a cold calculation of what you as an individual put in and what you as an individual get out.

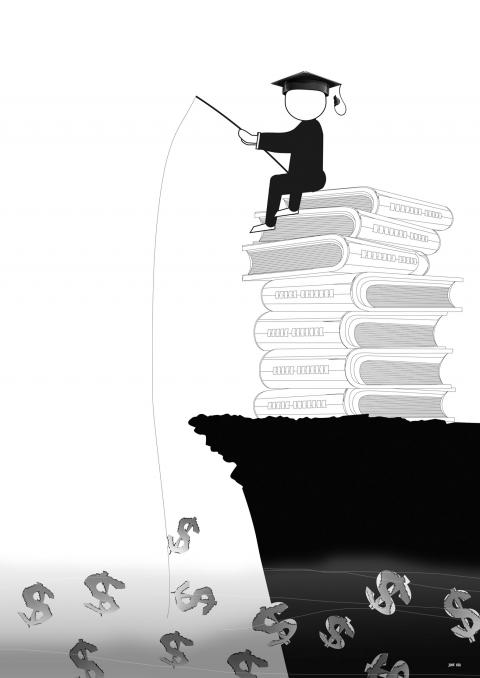

That is the premise for both Lord John Browne’s report into tuition fees and the debate that’s followed. The starting assumption has been that a university education is to be viewed solely as a personal asset, and those lucky enough to get it should foot the bill. Not upfront, because that’s politically unpalatable, but afterwards in the form of a personal debt. What’s more, the more prestigious the course or university, the more recipients should pay, since their personal earning power will be enhanced, said Browne, a former BP chief executive. There has been much talk about the mechanics of payback — when and at what rate — but few have contested Browne’s premise: that students are essentially consumers who should pay for services they receive — the more upmarket, the higher the price.

Illustration: June Hsu

Yet this is a radical departure from how we once conceived the public realm. Before former British prime minister Tony Blair introduced tuition fees, higher education was seen as a social good, enriching our whole society rather than merely an individual’s future salary. It sounds quaint now, but the purpose of universities was to hand down to the next generation the stock of human knowledge and add to it. They were about learning rather than earning.

That changed, particularly under New Labour, which transferred universities out of the Department for Education and into the Department for Business. Ever since, institutions of learning have had to justify themselves in terms of the economy and growth.

All right, you say, but that ship sailed long ago. Still, Browne has radically extended the business logic, opening the door to a world where a place at Oxford or Cambridge costs more than one at Keele, and a course in science sets you back more than one in theology. Some forecast that elite institutions will soon demand £12,000 (US$19,200) or even £20,000 a year. Even if the government sets the limit at £7,000, it still represents a shift in our very notion of public services.

Until now we have assumed that once you walk through the door into a universal, publicly funded service, cash should not enter your mind. When you visit a doctor, you aren’t asked which pills you’d prefer: expensive ones or the cheaper alternative. The idea would appal us. We expect a public service to be undifferentiated by cost.

Thanks to Browne and variability of student fees from college to college, higher education will no longer be like that. In the process a precedent has been set, one that could well be followed across the public sphere. From now on, it will be acceptable to identify the benefit recipients get from this or that service and ask them to pay more for it. We could well be looking at the dawn of what my colleague Aditya Chakrabortty calls the pay-as-you-go state.

It fits with the picture emerging of how this government sees the public realm. Last week’s move to end the universality of child benefit — removing it from higher-rate taxpayers — offered a glimpse of a smaller state, in which once universal services are provided in minimal form only to those with real need. In a financially cold climate there is hard-headed logic to such a scaling back, but we should not pretend that it does not entail a different vision of society, away from one in which there are ties binding us all and toward one that is more, well, transactional.

What would be a better way of doing it? Once you view higher education as a shared, public good — rather than just a prize for individuals — then several alternatives suggest themselves. If higher education from general taxation is politically impossible, especially in the age of cuts, what about asking more from those sectors that benefit directly from universities? We’re always told how essential graduates are for business and growth so perhaps we should be asking companies to pay their fare share via increased corporate tax.

There are other, more immediate dangers in the Browne approach. Even if students from low-income families are not deterred from applying to college altogether, they surely will be put off by the most expensive courses at the most costly institutions. This year’s survey by the National Union of Students and HSBC bank found that 70 percent of current students would have been deterred from applying had fees been set at £7,000 — and that percentage rose further down the income scale.

Lee Elliot Major of the Sutton Trust, which explores social mobility and education, said that pupils from non-privileged backgrounds “already rule themselves out from applying to Oxbridge because they perceive the costs as being higher.”

If that becomes fact, he predicts even more will stay away, no matter how many financial support mechanisms are put in place.

The result will surely be an education system defaced by privilege more deeply even than the one we have now. The children of the well-to-do — already growing, rather than declining, in number at the most prestigious universities — will cope fine: Many of their parents will regard university as no more than another three years of school fees. But the rest will be shut out.

Nor is it good enough to promise graduates vast earnings. It has been said that graduates can expect over their working lives to earn £100,000 more than those without degrees, but that figure was calculated when less than 10 percent went on to higher education. Now that nearly one in two go to university, it’s a matter of basic economics that a commodity in greater supply — graduates — will command a lower price. Instead of promising a vastly increased salary, a degree may be a basic requirement to enter large swaths of the white-collar British workplace — and yet a major obstacle is put in the way of those families that don’t have much money. The implications for social mobility will surely be profound.

Already, tuition fees have created a culture of debt among a generation who emerge into adulthood drenched in red ink, with liabilities that can take a decade to clear. Under the Browne plan students could leave college with a £40,000 debt, meaning some will struggle to break even their whole life.

And, let us not forget, the government’s response to Browne was announced by Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills Vince Cable, speaking for a party that signed a written pledge in April not to increase tuition fees. Last week Cameron had to apologize for ending universal child benefit after an election campaign in which his party had vowed to do no such thing. It took several years for New Labour to break the public trust; the coalition has done it in just a matter of months. The spending axe may barely have fallen, but trust in politics is already in shreds.

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its

When a recall campaign targeting the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators was launched, something rather disturbing happened. According to reports, Hualien County Government officials visited several people to verify their signatures. Local authorities allegedly used routine or harmless reasons as an excuse to enter people’s house for investigation. The KMT launched its own recall campaigns, targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers, and began to collect signatures. It has been found that some of the KMT-headed counties and cities have allegedly been mobilizing municipal machinery. In Keelung, the director of the Department of Civil Affairs used the household registration system