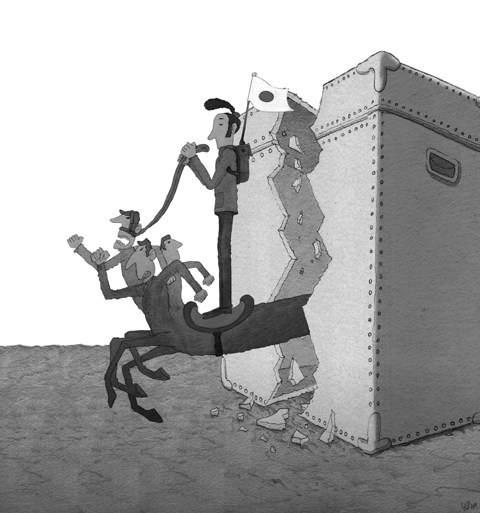

What does a political party built on power and patronage, with few philosophical or ideological underpinnings, do when it is defeated and driven into the opposition? In the case of Japan’s once formidable Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), it implodes like an old Las Vegas hotel being demolished.

This has led to hand-wringing in the Japanese press that the nation may be headed toward another period of de facto one-party government, only this time with the ascendant Democratic Party in charge. But optimists here say the Liberal Democrats’ decline may be just the first step toward a much bigger political change: The destruction of the old structures of Japan’s stunted democracy and the rise of new, more ideologically coherent parties in a livelier and more competitive political system.

To see how far the Liberal Democrats have fallen, look no further than the party’s cavernous headquarters in central Tokyo. The nine-story building, once the unchallenged seat of political power during much of the Liberal Democrats’ half-century rule of Japan, has fallen eerily quiet and underused since the party’s historic election defeat last summer.

The party has become an empty shell of its former self. Thrust into the role of opposition party for the first time since its creation in 1955 (aside from a brief interlude in 1993), and with its number of lawmakers cut in half by last August’s humiliating defeat, the party appears demoralized, devoid of fresh ideas and threatened by defections. Four lawmakers have indeed defected since the election, and speculation is rife that more will follow.

The party’s public approval ratings have never bounced back from the high teens, even as last summer’s victor, the Democratic Party, has suffered a series of money scandals. The party’s own internal newspaper, the weekly Liberal Democrat, even warned last month that the party had virtually no hope of survival.

“We haven’t had experience as an opposition party,” said Sadakazu Tanigaki, the LDP chief and a former finance minister, who sat in a room filled with the unsmiling portraits of past party leaders. “People are running around wondering, ‘What do we do?”’

For now, the contrast with the newly incumbent Democrats could not be starker. Despite fund-raising scandals, the Democrats still seem to brim with enthusiasm for their agenda of change, evident in their bustling, overcrowded offices just a block away, on a few floors of a building with a Pentax sign on top.

With the Liberal Democrats in such obvious disarray, some now fear Japan faces the prospect of one-party rule by the Democrats. But many analysts and politicians say they do not expect the Democrats’ hegemony to last long either, because they face many of the same weaknesses as the Liberal Democrats.

“The Democratic Party has the same problem as the LDP, in that both are broad tents filled with politicians of all ideological stripes,” said Takeshi Sasaki, a professor of politics at Gakushuin University in Tokyo. “So long as Japan lacks modern political parties, it will lack true political competition.”

The Liberal Democrats, Sasaki and others say, ruled through much of the Cold War with a hazily conservative platform built upon the bedrock of a close alliance with the US, which also became a market for its exports. At the same time, it built up an imposing political machine that redistributed the fruits of Japan’s postwar economic miracle to voters in less developed rural regions.

Without that patronage machine, the party risks flying apart. In that, analysts say, it is more like the PRI in Mexico, which has yet to recover from its battering in 2000 after more than 70 uninterrupted years in power, than like political parties in the US and Europe.

“We never found a new direction after the fall of the Berlin Wall,” Tanigaki said, “and we are regretting that now.”

The party’s shortcomings have become painfully apparent since its defeat, as it has failed to offer a clear-cut alternative to the Democrats’ vaguely left-leaning plans to offer more aid to families and become more independent from Washington.

Instead, the Liberal Democrats have adopted a short-term strategy of attacking Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama for the funding scandals involving him and the Democrats’ power broker, Ichiro Ozawa. This has brought some support from voters, seen last Sunday when a Liberal Democratic candidate won an election for governor of Nagasaki Prefecture. But political analysts and politicians say the approach could backfire if it appeared to lead Japan back into its former political paralysis.

Indeed, there is growing frustration among conservatives at the party’s inability to change. This became apparent last September, when Tanigaki, 65, defeated a younger opponent, Taro Kono, 47, to lead the defeated party. Many younger lawmakers saw this as a move by the party’s old guard to squelch Kono’s promises to rejuvenate the party by such steps as abolishing its entrenched factions.

Kono said the Liberal Democrats’ only hope of victory was to reinvent themselves as a truly conservative party, with a clear agenda of small government and close ties with the US. But he sounds a very pessimistic note about the party’s future, so long as the old guard holds sway.

He said the Liberal Democrats faced their next big test in parliamentary elections in July, when another defeat could prove a death blow.

“People don’t want the old Liberal Democratic Party,” Kono said. “They want us to come back as a new, healthier party.”

But even if the Democrats win, they may soon face similar problems of internal divisions over policy, especially if they move beyond their current manifesto and into trickier issues like whether to raise taxes or cut social programs to rein in the budget deficits. When that happens, say analysts, the party could also break apart, paving the way for the radical reshuffling of parties along ideological lines that would complete the political revolution begun last summer.

“After the breakup of the Liberal Democrats, it will be the Democrats’ turn to fight internally and split,” Kotaro Tamura, a LDP lawmaker who left in December to join the Democrats. “That will be a big moment for Japanese democracy.”

A few weeks ago in Kaohsiung, tech mogul turned political pundit Robert Tsao (曹興誠) joined Western Washington University professor Chen Shih-fen (陳時奮) for a public forum in support of Taiwan’s recall campaign. Kaohsiung, already the most Taiwanese independence-minded city in Taiwan, was not in need of a recall. So Chen took a different approach: He made the case that unification with China would be too expensive to work. The argument was unusual. Most of the time, we hear that Taiwan should remain free out of respect for democracy and self-determination, but cost? That is not part of the usual script, and

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists