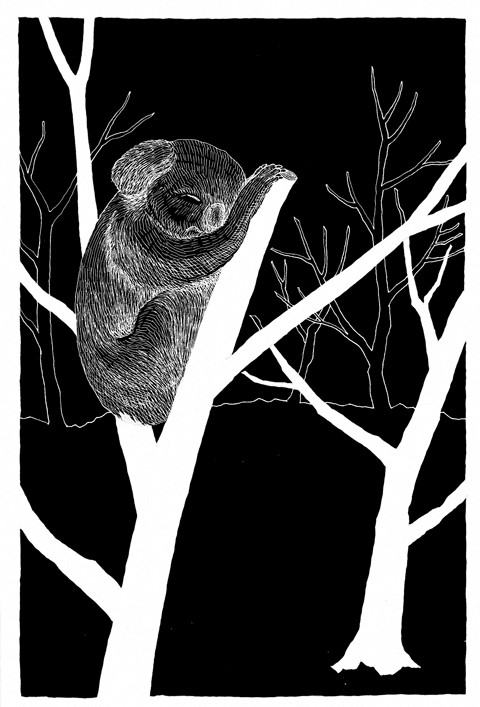

When southeastern Australia was consumed by bushfires in February, one image shut out all others. Nearly 200 humans might have perished, but a koala had been saved: Videoed in a blackened landscape drinking thirstily from the water bottle of a volunteer firefighter, Sam featured in newspapers from the New York Times to the UK’s Sun and became a hit on CNN, YouTube and a Web site created by her veterinary caregivers.

Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said she was the subject of widespread comment at the G20 summit in London in April and he issued a personal tribute to the “symbol of hope” when Sam died six months later.

“It’s tragic that Sam the koala is no longer with us,” Rudd said, just restraining himself from decreeing a state funeral.

Two weeks ago in Canberra, representatives of the Australian Koala Foundation (AKF) took a long and determined campaign for better protection of the creature to the government’s “threatened species scientific committee,” following a request for a review of the animal’s status by Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts Peter Garrett.

The foundation presented what it said was definitive evidence of a sharp decline in koala numbers because of habitat destruction and disease. Its message was stark: The koala would be extinct “within 30 years.”

Hits on its Web site instantly doubled and concerns were expressed about the impact on Australia’s tourist industry: Polls consistently show the koala to be the country’s most popular animal with visitors.

In the AKF’s chief executive Deborah Tabart, meanwhile, Rudd faces an implacable and outspoken critic, one who will now be dogging his steps at next month’s Copenhagen climate change conference. Rudd may have been nice about Sam the koala, but Tabart does not think Rudd is doing enough for the species.

She describes him as a “bureaucrat who hides behind policy and writing documents”

The koala, she mutters darkly, “has many powerful enemies.”

It has certainly had its detractors. The koala features in fossil records as far back as 25 million years ago and has an honored place in Aboriginal creation myths, but when naturalist Gerald Durrell described it as “the most boring of all animals,” he was far from the first to do so.

The koala is assuredly a creature of leisure. It has the smallest brain proportionally of any mammal, sleeps most of the day and dedicates much of the rest to chewing gum leaves. The first description published in England 200 years ago, in fact, introduced the koala as the “New Holland Sloth.” In his Arcana; or The Museum of Natural History, published in 1881, the naturalist George Perry was severely censorious of the koala’s “sluggishness and inactivity” and thought its “clumsy appearance” was “void of elegance.”

“We are at a loss to imagine for what particular scale of usefulness or happiness such an animal could by the great Author of Nature possibly be destined,” said Perry, although his respect for that particular author compelled him to concede: “As Nature however provides nothing vain, we may suppose that even these torpid, senseless creatures are wisely intended to fill up one of the great links of the chain of animated nature, and to shew forth the extensive variety of the created beings which GOD has, in his wisdom, constructed.”

Nor was the koala then prized for cuddliness, being widely hunted for its fur from the 1870s, and provoking relatively little interest abroad. The first specimen to make it to England met an untimely end in the office of the superintendent of the Zoological Society, asphyxiated by the lid of a washing-stand that fell on its head.

The koala’s installation in national favor owes much to eager exercises in anthropomorphism in the early 20th century, first in cartoons published in the legendary nationalist periodical the Bulletin, then in children’s tales such as Norman Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding and Dorothy Wall’s Blinky Bill.

Lindsay offered Bunyip Bluegum as a koala of culture, with boater, bowtie and walking stick, while Wall’s Blinky was a marsupial of mischief, dressed in knickerbockers and bearing a knapsack, although sufficiently patriotic to join the army during World War II.

If it was considered inadequately industrious for the 19th century, the koala was exquisitely suited to the cuteness-conscious 20th. Indeed, it is appropriate that the AKF’s case is accented to the environmental pressures the koala faces in Rudd’s home state of Queensland, where it is the faunal emblem, and has always had political claws.

It was in Queensland that the koala was the subject of Australia’s first concerted environmental campaign after the state Labor government, in response to pressure from trappers who had denuded koala populations to the south, proclaimed an open season on the animal in August 1927.

Resistance orchestrated by the Queensland Naturalists Club and the Nature Lovers’ League inspired one newspaper to print an edition bordered in black, and flushed out celebrity apologists including writer Vance Palmer.

“The shooting of our harmless and lovable native bear is nothing less than barbarous,” he thundered. “There is not a social vice that can be put down to his account ... He affords no sport to the gunman ... and he has been almost been blotted out already in some areas.”

The trappers had their way, slaughtering and skinning no fewer than 1 million koalas, but the Labor government paid the price, being swept from power at the next election. Australia’s first three fauna parks, set up in the late 1920s, were dedicated to koalas.

Researching all this for his book Koala: The Origins of an Icon, biologist Stephen Jackson was astonished by the ardor he encountered.

“You read now what was being published then, and you think: ‘Wow! These people really went off.’ It’s almost the beginning of the conservation movement in Australia, because it mobilised people as never before,” he wrote.

Seventy years after that pioneering koala campaign, for example, federal tourism minister John Brown famously dismissed the animals as “flea-ridden, piddling, stinking, scratching, rotten little things”; he left politics soon after following allegations he had misled parliament over a tender submitted by a contractor.

The 1995 state election was then dominated by a Labor government plan to drive a major roadway through a key koala habitat. An apparently unassailable majority dwindled unsustainably when Labor lost what became known as the “koala seats” in Brisbane Bayside. Oddly, Rudd — then chief-of-staff to the premier of Queensland — was mixed up in the row over that koala habitat.

In the end, those koalas probably did Rudd a favor — and now Tabart thinks it is payback time. She is an unpredictable political opponent.

An entrant 40 years ago in the Miss Australia pageant, she explains her failure candidly: “I didn’t sleep with one of the judges, so I didn’t win.”

Tabart has made a particular target of Bob Beeton of the University of Queensland, the chairman of the aforementioned threatened species scientific committee, which four years ago rejected an AKF application for listing of the koala as “vulnerable.”

“That determination sits on my desk to this day, and it outrages me,” she says.

To Beeton’s statements that his committee might take up to a year to report back to environment minister Peter Garrett, she retorts: “The minister doesn’t have that time — and nor does the koala.”

Beeton has a droll line or two as well. While naturalists describe the koala as representative of “charismatic megafauna,” Beeton is unmoved by charisma. Under pressure from a television interviewer last week, he responded that his committee would grant protection of the koala as much consideration as protection of the death adder — the subject of another recent determination.

Asked about advocacy groups in general, and the proposition that no such group has ever prospered from buoyant pronouncements of abundance, he invokes Francis Urquhart in House of Cards: “You might well think that. I couldn’t possibly comment.”

Far from being new, Beeton observes, disease is a perennial problem in the koala community. The Chlamydia organism, which finally carried off Sam, may be present in as many as half of Australia’s koalas — just as it is also present in about a third of humans.

Another specter cited in recent publicity concerning the koala is a newly identified but little understood retrovirus, originally given the acronym KoRV, but now more catchily abbreviated as KIDS (Koala Immune Deficiency Syndrome). Beeton believes that a great deal more needs to be known about the condition.

“It’s very hard for a single disease to kill a species,” Beeton says. “We couldn’t kill rabbits in Australia with myxomatosis.”

There is clearly much argy-bargy to come. The AKF’s prospects will depend on its ability to use global concerns to influence domestic policies; for Australians, the koala reposes, at least at the moment, on a list of “things-to-be-concerned-about-had-I-the-time.”

So far, it has made its case with only a broad brush. Because of her suspicions of the Species Committee, Tabart says that the foundation is unprepared as yet to divulge full details of its data, on grounds that earlier data presented to the Species Committee was “used against the koala.” She will say only that it results from the examination of 80,000 trees at 2,000 field sites and concludes that the population may be as low as 43,000, compared with previously assumed figures comfortably in six figures.

This leaves the foundation open to criticism because, as Jackson points out, koala numbers depend quite heavily on where you look: “If you talk to biologists [in Victoria], they’ll tell you: ‘Koalas are falling out of the trees down here. We don’t know what to do with them.’”

Statistics that are public, however, include those of widespread land clearing in Queensland until its cessation in January 2007, after a decade in which up to 700,000 hectares of habitat was being destroyed annually under the influence of property developers and resources companies — a reckless abandon of which the environmental effects are still little understood.

In this sense, Sam the koala was an ironic representative of her species, survivor of a calamity amply publicized and readily understood; far greater ecological damage on Australia has been inflicted by easy government acquiescence.

When US budget carrier Southwest Airlines last week announced a new partnership with China Airlines, Southwest’s social media were filled with comments from travelers excited by the new opportunity to visit China. Of course, China Airlines is not based in China, but in Taiwan, and the new partnership connects Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport with 30 cities across the US. At a time when China is increasing efforts on all fronts to falsely label Taiwan as “China” in all arenas, Taiwan does itself no favors by having its flagship carrier named China Airlines. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is eager to jump at

The muting of the line “I’m from Taiwan” (我台灣來欸), sung in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), during a performance at the closing ceremony of the World Masters Games in New Taipei City on May 31 has sparked a public outcry. The lyric from the well-known song All Eyes on Me (世界都看見) — originally written and performed by Taiwanese hip-hop group Nine One One (玖壹壹) — was muted twice, while the subtitles on the screen showed an alternate line, “we come here together” (阮作伙來欸), which was not sung. The song, performed at the ceremony by a cheerleading group, was the theme

Secretary of State Marco Rubio raised eyebrows recently when he declared the era of American unipolarity over. He described America’s unrivaled dominance of the international system as an anomaly that was created by the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Now, he observed, the United States was returning to a more multipolar world where there are great powers in different parts of the planet. He pointed to China and Russia, as well as “rogue states like Iran and North Korea” as examples of countries the United States must contend with. This all begs the question:

Liberals have wasted no time in pointing to Karol Nawrocki’s lack of qualifications for his new job as president of Poland. He has never previously held political office. He won by the narrowest of margins, with 50.9 percent of the vote. However, Nawrocki possesses the one qualification that many national populists value above all other: a taste for physical strength laced with violence. Nawrocki is a former boxer who still likes to go a few rounds. He is also such an enthusiastic soccer supporter that he reportedly got the logos of his two favorite teams — Chelsea and Lechia Gdansk —