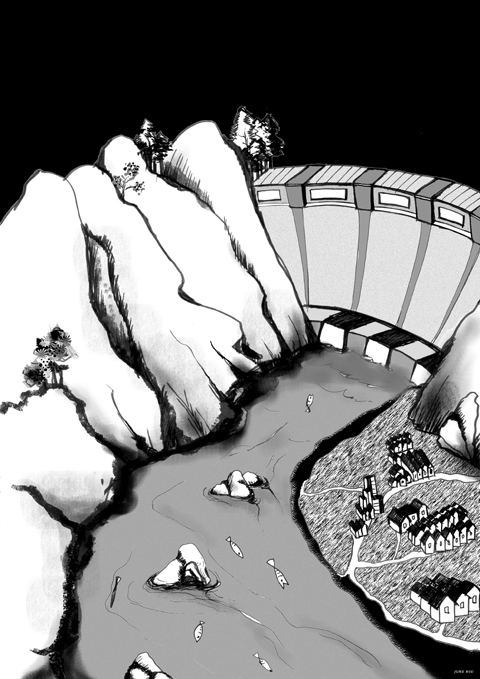

First, the farmers objected to an ambitious dam project proposed by the government, saying they did not need irrigation water from the reservoir. Then the commercial fishermen complained that fish would disappear if the Kawabe River’s twisting torrents were blocked. Environmentalists worried about losing the river’s scenic gorges. Soon, half of this city’s 34,000 residents had signed a petition opposing the US$3.6 billion project.

Last September, this rare grassroots uprising scored an even rarer victory when the governor of Kumamoto Prefecture, a mountainous area of southern Japan, formally asked Tokyo to suspend construction. The ministry agreed, temporarily halting an undertaking that had already relocated a half-dozen small villages, though work on the dam itself had not started.

The suspension grabbed national headlines as one of the first times that a local governor had succeeded in blocking a megaproject being built by the central government. It also turned the governor, Ikuo Kabashima, into a new emblem of a broader rethinking of Japan’s highly centralized style of government, in which Tokyo’s powerful ministries have held a tight grip on decision-making, all the way down to local levels

“We can’t cower before the central government,” said Kabashima, a former politics professor.

The apparent victory brought a flurry of similar revolts by other regional governments against big public works projects. In November, four prefectural governments in the western Kansai region requested the cancellation of a planned dam, and earlier this month the governor of Niigata Prefecture refused to help pay for a new bullet train line. The governor of Osaka said the city would not finance a new bridge to an airport.

This backlash is partly a result of tighter budgets during the current economic crisis. But it also reflects how Japan’s long stagnation has brought growing criticism of the old top-down model, and efforts by regional leaders to change it.

Sensing the shift in political winds, even Japan’s long-governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which ran the old regime along with powerful bureaucrats, has jumped on the decentralization bandwagon. The administration of Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso says it wants to draw up a bill as early as this year that would replace Japan’s 47 relatively weak prefectures with nine to 13 larger entities that would have powers roughly analogous to US state governments.

It is unclear how realistic the proposal is, given Aso’s own unpopularity and intense opposition within the party and the bureaucracy. But the fact the idea emerged at all underscores how the Kawabe River Dam’s suspension has helped rekindle the debate here over whether to hand more power to localities.

“The Kawabe River Dam is a symbol that Tokyo cannot just impose its will on the regions anymore,” said Yoshihiro Katayama, a political professor at Keio University and former governor of Tottori Prefecture. “Public opinion is shifting against the central government and its missteps.”

In planning the Kawabe River Dam, the government tried to brush aside local doubts about dams going back to an accident 44 years ago when the sudden release of water from a smaller dam during heavy rainfall caused a flash flood that killed one person in Hitoyoshi, in Kumamoto Prefecture.

The suspension also drew national attention because citizen groups played a large role, something unusual in a country used to following Tokyo’s lead. Local environmentalist groups, backed by farmers, fishermen and operators of rafting trips on the river’s rapids, demanded greater openness in decisions traditionally made behind closed doors between politicians and central government bureaucrats. They challenged the Construction Ministry’s arguments that the dam, which was first proposed in the 1960s, was needed for irrigation and flood control.

Under pressure from these groups and prefectural officials, the Construction Ministry made a rare concession, agreeing to hold public hearings to explain the dam and hear residents’ concerns. Some of the hearings devolved into shouting matches between dam opponents and construction industry workers who wanted the jobs, residents said.

In the end, the ministry appeared unable to present a convincing rationale for the project, and opinion polls show that around 85 percent of voters in the prefecture now oppose the dam.

“People realized they could speak up against the national government,” said Nobutaka Tanaka, mayor of Hitoyoshi, who won office two years ago on an anti-dam platform. “In the old days, if officials said it was for the nation, everyone felt they had to be silent and accept it.”

An overreliance on public works spending has also created a huge burden for local governments, which are required to pay a third of the cost of national infrastructure projects. And now, with municipal budgets under increasing strain, local governments are demanding a bigger voice in spending decisions.

Japan’s prefectural and municipal governments are now saddled with some US$2.1 trillion in outstanding debt, substantially below the national government’s US$6.5 trillion but still the equivalent of 39 percent of Japan’s entire economy, the Ministry of Internal Affairs says. By contrast, state and local government debt in the US totals about 16 percent of the US economy, the Census Bureau says.

Early this decade, independent governors in cash-strapped prefectures began opposing public works dictated by Tokyo. The reformist former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi also shifted some tax revenues and fiscal responsibilities to local governments. But never has a local government tried to nix a project as large as the Kawabe River Dam. The backlash has put the powerful Construction Ministry on the defensive. The ministry agreed to a sweeping review of all its dam projects, saying it would make a final decision on the Kawabe River Dam by year’s end.

“They paint us as the bad guys who want big projects,” complained Senior Vice Minister of Construction Yasushi Kaneko, a Kumamoto native who said the Kawabe River Dam was needed for flood control.

Kabashima, who won election last year as a conservative backed by the LDP, said he was on the fence about the dam until he saw the depth of public opposition.

He said that his request to suspend the dam is not a rejection of public works, which Kumamoto still depends on for jobs. Nor is it about saving money, since he said the prefecture will have to spend heavily to clean up the unfinished construction.

“Kasumigaseki’s self-confidence is down,” Kabashima said, referring to the district in Tokyo where the national ministries are located. “Now is the time for Japan to decentralize.”

A few weeks ago in Kaohsiung, tech mogul turned political pundit Robert Tsao (曹興誠) joined Western Washington University professor Chen Shih-fen (陳時奮) for a public forum in support of Taiwan’s recall campaign. Kaohsiung, already the most Taiwanese independence-minded city in Taiwan, was not in need of a recall. So Chen took a different approach: He made the case that unification with China would be too expensive to work. The argument was unusual. Most of the time, we hear that Taiwan should remain free out of respect for democracy and self-determination, but cost? That is not part of the usual script, and

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed