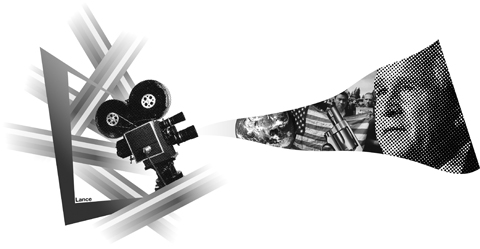

Every once in a while, a culture shifts. You feel like a Luddite until your new learning curve is complete. That is the experience I have been having recently, as my book The End of America has been turned into a documentary. Can political documentaries make a difference? For someone who lives mostly in the dimension of words, it is an exciting and scary question.

The End of America details the 10 steps that would-be dictators always take in seeking to close an open society; it argued that the administration of former US president George W. Bush had been advancing each one. I took the message on the road, and one of those early lectures — at the University of Washington in Seattle, in October 2007 — was videoed by a member of the audience. Even with its bad lighting and funky amateur vibe, this video, posted on YouTube, has been accessed almost 1.25 million times.

This was a humbling lesson. While a polemical argument in prose may reach tens of thousands of the usual suspects — formally educated people who like to follow such texts — the video version reached far beyond that audience. Everywhere I went, from the gas station to the nail salon, I ran into people who would have been unlikely to read a book of mine, but who were passionately supportive of the argument from having watched it on YouTube.

The medium really is the message, in this case. For any opposition to Bush’s assault on liberty to be real, we would need hundreds of thousands of Americans from all walks of life to become outraged. Many other videos and films helped reached those masses, including Taxi to the Dark Side, Alex Gibney’s documentary about US brutality towards terror suspects, which last year won an Academy award, at a time when the major newspapers were still queasy about calling Bush interrogation tactics torture.

My humbling experience of the limits of print was taken one step further by a team of documentary-makers, Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg (who together made the inspired The Devil Came on Horseback, a film that single-handedly raised awareness of the Darfur crisis in the US). As they worked on their film of The End of America, I experienced something incomparably fascinating for a non-fiction writer: sources I had quoted at length from the written record — and felt close to, for that reason, but abstractly — were interviewed in person, with all their humanity and quirkiness. Oh my God: there was Captain James Yee, the Guantanamo chaplain framed and held in a navy brig in isolation, because he spoke up against abuse of the detainees. There he was in his living room! Wow: here was Colonel David Antoon, the Vietnam veteran, fighter pilot and Iraq war critic, breaking down in tears as he described the harassment of his elderly mother. These voices came to life with surreal vividness.

I also saw the power of news footage, both archival and contemporary, to move the emotions in a way that my poor computer could never do. It is one thing to invoke in prose the history of how Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet rounded up citizens for violent intimidation, and another to see actual footage of people who look like you and me dragged off by the hair in modern city streets. It is one thing to analyze a militarized post-Sept. 11 US police response to protesters, and another to watch never-before-seen footage of US police officers — now trained by Homeland Security, and dressed like Darth Vader in helmets and black body-armor — engage in mass sweeps of terrified citizens in St Paul, Minnesota, including parents with children, and dragging a frightened reporter, Amy Goodman, off by her sweater. (Since police destroyed most cameras at last year’s Republican National Convention, the footage survived only because a protester buried his camera underground as he was being arrested.)

Is this medium effective in bringing about change? A follow-up video I made with a young dissenting Iraq war veteran, Sergeant Mathis Chiroux, shows smuggled-out footage of mounted police officers deliberately trampling Iraq war veterans with their horses; one young man’s face was trampled so badly that a metal plate had to be installed under his eyeball. After this interview aired on YouTube, the vets went from facing charges to seeing their charges dropped; the Long Island district attorney initiated an investigation into police brutality. Could writing alone — an outraged editorial — have managed that, these days, so quickly? Very unlikely.

The history of documentary film is nearly 100 years old, and its tradition owes much to early documentarians in the UK in the 1920s and 1930s. In the US, the 1950s and 1960s marked the documentary’s golden age, especially at CBS, where pioneering television journalist Edward R Murrow, immortalized in George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck, produced such landmark investigations as the CBS Reports program Hunger in America.

Recent heirs to this tradition include such films as Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth — which, with his book, arguably did more to raise mass awareness of the reality of global warming than any amount of print analysis, or legislative debate, might have. At a time when investigative print reporting is withering, through shrinking newspaper budgets and readerships, when journalism schools are turning out fewer and fewer investigative reporters for that reason, one could argue that documentaries are becoming our main source of investigative journalism.

But remember: Gore brought out his film along with his book. For all the power of video and film, I am not giving up my pen. I am just much more likely to try to link essays to Webcasts or videos. The best way for these two media to move forward, to inform and make change, is in tandem; together they are more than the sum of their parts.

Documentary film without nuanced journalistic sourcing risks being sensational, tendentious or broad-brushed. And these days, print without a dimension of imagery risks being flat, especially to a younger audience. So while we need not despair about the future of investigative journalism, or the power of print alone to drive change, we writers should accept the inevitable: Those damn film-makers have tools we need to adapt to, and, wherever possible, appropriate. Wherever we want to turn out the deathless prose of political polemic to drive great change — well, we just have to smuggle out the video footage to go with it.

Naomi Wolf is the author of The End of America and its sequel, Give Me Liberty: A Handbook for American Revolutionaries. The End of America is out on DVD.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its