They call them the “walking clubs,” and Grace Sibanda is an involuntary member. Each working day, the 36-year-old shop assistant rises before dawn in Dzivaresekwa township to the west of Harare, slips out of her tiny home without waking the three children who share her bed, and makes her way to the clusters of people gathered at the roadside. When there are enough of them — a few dozen usually — they set off on the three-hour walk to work in the city center.

“We are lucky to have jobs but the bus fare in one day is more than I earn in a week. So we walk,” she said. “We walk together because it’s not safe. They wait in the bushes by the road and attack you if you are alone. They don’t want money. We don’t have any. They want my food.”

Sibanda holds up a plastic bag with her lunch of fruit and vegetables. Bread long ago became an unaffordable luxury.

“No one believes what has happened to our country. Now we talk of prices in billions of [Zimbabwean] dollars and people are asking what comes after trillions. They laugh about it but we know it’s not funny. People are dying. I wonder how long I will be able to feed my children,” she said.

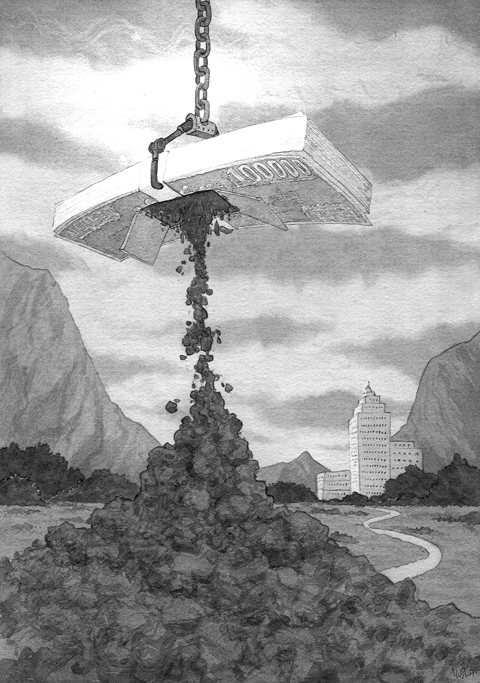

Around Harare, in the dark of the cold winter mornings, the walking clubs can be found setting off. But the numbers have been falling as jobs disappear under the barrage of hyperinflation — currently estimated to be about 9 million percent but predicted to hit 100 million percent within three months — and a currency devaluing so fast that banknotes issued just a few months ago are now not worth enough to buy a single sheet of toilet paper.

That is, if toilet paper could even be found in the empty supermarkets. Zimbabwe’s economic and political crisis has wormed its way in to almost every aspect of everyday life as people spend their days struggling with intermittent power supplies and water shortages, or waiting hours in queues for bread or cash. Many schools and hospitals barely function as teachers and nurses flee to South Africa in search of a salary that can feed their families back home. And deep in some rural areas, Zimbabweans are saying that starvation is taking hold for the first time in living memory.

Zimbabweans used to feel sorry for their war-blighted neighbors in Mozambique, who were forced to cross the border to buy the most basic goods. Now lines of Zimbabweans, black and white, line up at the checkout tills in Chomoio, across the Mozambican frontier, loaded down with bread, flour and tinned foods because the supermarkets at home are all but empty.

Zimbabweans also used to laugh at Zambia’s currency, the kwacha, as Monopoly money. Nowadays, in Victoria Falls on their own side of the border, Zimbabweans are using kwacha as a hard currency, while the Zimbabwean dollar loses half its value every few days.

ONE TO BILLIONS

In August 2006, Zimbabwe’s central bank issued a one cent note. In May, it issued a Z$50 billion note. At the time it was worth about US$4; now it is just US$0.34, and that won’t be for long. Meanwhile, an advert in Thursday’s Harare Herald newspaper trumpeted that this week’s Lotto bonanza is “Z$1.2 quadrillion” in prizes (US$4,200 on Friday).

Inflation means hourly price rises while wages — for those lucky enough to have a job in a country with more than 80 percent unemployment and industry virtually at a standstill — lag far behind. Sibanda earned Z$150 billion last month. Police officers and teachers made about the same. At the time, it was enough to buy 20 eggs or about 10kg of maize on the black market.

Increasingly people are getting by on one meal a day and praying that they don’t get sick. Few can afford to go to hospital. In any case, they rarely have drugs or staff, as so many of the doctors and nurses have fled abroad in search of a living.

In one of Harare’s upmarket suburbs, Ishmael Dube is having to sell off the trappings of his life, despite a long history of close association with Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe’s government. Testament to this are the two government-issued identity cards carried by the warm, if pensive, 60-year-old. One says he is a “Liberation War Hero.”

Dube took up arms against white rule in 1966 at the age of 18. He was captured by the Rhodesian army a year later and served 15 years in jail as a “terrorist.” The other says he is a former staff member of Mugabe’s presidential office. After independence in 1980, Dube became an intelligence officer on Mugabe’s staff and then went on to a diplomatic career, serving in Europe and Washington. He retired a decade ago and lived comfortably enough on two pensions. No more. This month his war veteran’s pension brought him Z$109 billion and the other, for his government service, Z$130 billion.

With that he is expected to feed his wife and seven daughters. He also has to pay for four of his daughters to go to university, two to go to primary school and the seventh to board at a secondary school.

“I can buy a bucket of maize with my pensions. That keeps us going for about five days. So how can we survive?” he asked.

Dube is doing what so many Zimbabweans — from the once well-off to the poor — have to do these days: hawking his possessions piecemeal.

Dube retired as a diplomat owning two cars. He brought three television sets back from Washington. In the 1990s, like many in Zimbabwe’s rising black middle class, he accumulated the goods and chattels that flow from a comfortable income. Now most of them are gone.

“I’ve sold the two cars to pay for the girls to go to university. First one car two years ago, then the other. I don’t have a vehicle any more. Then I’ve been selecting certain household items to sell. I used to have three TV sets. I sold two. I sold the washing machine. Last month I sold my radio stereo to another parent at my daughter’s school, Queen Elizabeth, for Z$1 trillion,” he said.

“I owe the school Z$1.2 trillion in fees but I had to use some of the money to buy food so I’m trying to negotiate with them to pay Z$500 billion monthly,” he said.

But the school wants the money now because at 9 million percent inflation it is virtually worthless in a month.

Dube at least has something to sell. Retired people across Zimbabwe have seen their pensions wiped out by inflation and increasing numbers live on handouts from organizations such as Save Our Ageing Pensioners. Sometimes the elderly looked after by local women paid a comparative fortune — US$150 a month — by relatives abroad. Mugabe calls them BBCs: British Bum Cleaners.

Dube wants to meet in the burger bar at what had been one of Harare’s most upmarket shopping malls, the Westgate complex. It was built with South African money a decade ago and attracted boutiques and bookshops. Most are closed now. Dube wants to order chips but the waitress says there aren’t any. No hamburgers, either, despite the luridly colored menu on the table offering the usual meat-filled buns. Instead she lays down a worn photocopy of typed offerings. The list includes pig’s trotters and knuckle bones at Z$90 billion a dish.

“A lot of us have been diagnosed with high blood pressure,” Dube said. “It’s not surprising. We’ve been relying on beer for stress management — a drink or two a night. But beer last week was Z$10 billion a quart [0.94 liter]. This week [of July 7] it was Z$20 billion. On Wednesday [July 9] it was Z$40 billion and now it is Z$60 billion. So this thing we have been using as stress management is beyond our reach. That is very bad.”

By Thursday, beer was Z$150 billion a quart.

BLACK MARKET

Many people, Dube said, have found themselves forced to become black market traders.

“More or less every family finds it imperative to have a vendor,” he said.

Walking long distances into the countryside to buy food to resell in the towns is one way of trading. People used to be too scared to disobey the law requiring maize growers to sell their crops to the state-run Grain Marketing Board at a predetermined price, but these days hunger often overcomes fear.

“The maize is coming in to the city direct from the few farms able to harvest,” Dube said. “You see people on the roads. They walk 30km carrying 50kg of maize. They buy it at Z$30 billion and sell it at Z$250 billion. A lot of people are doing that. Not only maize but beans and vegetables.”

Sibanda’s mother is among them. The shop assistant cannot survive on her pay alone so she gives it to her mother who travels back to her rural village to buy vegetables. She brings them back to the city and sells them, along with cooking oil by the cup, on a stall she has set up on a few planks of wood and bricks in Dzivaresekwa.

“We make more money from selling the vegetables than I earn, but I don’t want to give up my job — I may never get another one,” Sibanda said. “My money used to be enough to pay for everything — food, clothes, school. We could afford to take bus trips to places. Now we don’t go anywhere we can’t walk.”

Even for those with money, shopping is a logistical nightmare. The first problem is to get hold of cash. The central bank cannot print it fast enough to keep up with demand. But neither does anyone want to hold on to it very long when prices are rising by the hour. So there is a merry-go-round of cash in which people line up for hours to draw their allotted Z$100 billion limit from the bank each day but then spend it as fast as possible before it loses what little value it has. It is still possible to write checks, but shops demand that they are made out for twice as much as the bill, because checks lose half their value while clearing.

Zimbabwe has a fairly advanced electronic banking system so it is possible to bypass the cash shortage by using a debit card. But the limits on individual transactions mean a basket full of groceries requires the card to be swiped dozens of times to pay the bill. Some supermarkets have staff standing full-time at the card machines and lines of customers waiting to pay.

Other supermarkets have no such problem because they have nothing to sell. Smaller shops with government connections, such as Spar, import many of their goods from South Africa and sell them well above the price-controlled rate. But the larger chains — such as TM and OK — are closely watched by the authorities and can no longer afford to sell at official prices that are a fraction of the real cost. Their shelves are bare except for locally produced vegetables and cleaning fluids. Even the baked beans factory has closed down.

Two weeks ago, the government accused both chains of conspiring to make “regime change” by starving people, and ordered them to stock their shelves or face their businesses being seized. When the owners protested that they could not afford to import goods that they were then only permitted to sell at prices substantially below cost, officials said that unless the shelves were filled within a week the state would take over.

FOREIGN CURRENCY

Those with hard currency — South African rand or US dollars — are increasingly drawn to underground supermarkets set up in warehouses. Shopping is by appointment, and customers are screened to ensure they won’t blow the whistle. It is a criminal offense to accept foreign currency in payment but in recent weeks some businesses have thrown caution to the wind. Restaurants even price in what they call “units,” a euphemism for US dollars. Gas at garages can be bought only with US dollars after drastic fuel shortages forced the government to accept that was the only way Shell and BP would bring it into the country. And increasingly, rents and salaries in private firms are pegged to the US dollar.

Much of the foreign currency comes from the 4 million Zimbabweans — one-third of the population — who have gone abroad for work. Most are in South Africa but some estimates say there are 1 million in the UK. The cash they send back to their families has now replaced tobacco as Zimbabwe’s single largest source of foreign earnings.

These foreign remittances mean there are enough people with money to buy what Dube has to sell.

“There are people who refurbish cars and sell them to people with relatives overseas who have money to send back. They are in the UK or South Africa. They get money from the sons and daughters. They even buy houses,” he said.

Zimbabwe’s property market is buoyant because exiles are buying up houses in Harare from people desperate for foreign currency. There is also a form of vulture capitalism, with foreign investors realizing that industrial property can be snapped up for far below its real value.

The collapse of their country is all the more shocking for many Zimbabweans because it has been so sudden. Nigeria, and what was then Zaire under the tutelage of former president Mobutu Sese Seko, slid into decay over three decades as their wealth was diverted to the pockets of an elite indifferent to the plight of those they ruled. Infrastructure, education, health care and jobs crumbled away. In parts of Zaire, the only people who had ever seen a car were the elderly. Zimbabwe, by contrast, was on the up. Its education system was arguably the best in Africa, a growing black middle class took root and aspirations flourished, sometimes being realized.

REMNANTS

The remnants of those times are still here. The ballet performs and Harare sports club continues with cricket on Saturday afternoon. The horses at Borrowdale race course compete for Z$100 trillion prize money in the Air Zimbabwe Handicap and Republic Cup. At first glance, little seems to have changed: the jockeys parade in colors, a smartly turned out army band strikes up between races. But the signs of erosion are everywhere. The dress code in the owners’ bar has fallen away. Entry is open to anyone with enough money for a beer, US dollars welcome. The minimum bet is Z$20 billion.

After the races, punters return to homes with no power and water. Some Harare suburbs haven’t had water in three months. Swimming pools are now personal reservoirs.

There is every sign the situation will get worse. Food has been in even shorter supply since the government banned foreign aid organizations from working in rural areas — a move that appeared to be an attempt to keep outside witnesses away from Zanu-PF’s campaign of terror against the voters in this year’s elections. Now people are beginning to starve.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that Zimbabwe will this year produce only about a quarter of the grain it needs to feed its people. The numbers being treated for malnutrition in hospitals have doubled in recent months. About 5 million people are expected to need food aid.

Yet so far, there has not been any of the popular protest — either against the economic crisis or the stolen election — that has hit other African countries at such times, most recently in Kenya.

“A lot of people regard Zimbabweans as docile,” Dube said. “But there’s docility based on intelligence that says if there’s a chance to survive there is no point in risking your life. But people have their backs against the wall and they are wondering if they can survive.”

“It’s firefighting. Us and them: ordinary people and the government. No one has a plan. We’re all just firefighting to get through each day,” he said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its