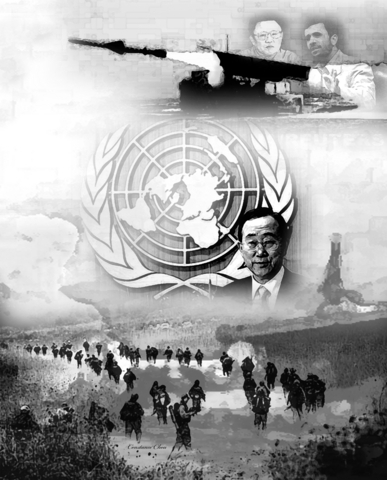

When asked about his qualifications for the post of UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon pointed to his role as South Korea's foreign minister charged with dealing with the North Korean nuclear threat.

No disrespect to Ban, but this is hardly a strong recommendation. Despite numerous warnings, and several opportunities to cut a deal, the North Korean nuclear question has steadily gone from bad to worse in the past dozen years. This month it became a mega-problem when Pyongyang detonated its first nuclear device.

Blame for this serial failure of diplomacy does not lie solely with Ban's South Korea or with the UN, the organization he has been appointed to lead. North Korea has if anything been a collective failure of imagination and determination.

Ban now says that he will appoint a permanent UN special envoy to North Korea when he takes over from UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan at the UN's New York headquarters on Jan. 1. He is also planning a trip to North Korea, where he will focus on human rights as well as weapons proliferation issues.

All the same, this month's North Korean developments have once again emphasized the severe limitations of the UN in its capacity as the foremost global institution when an international crisis erupts.

Prior to North Korean leader Kim Jong-il's latest adventure, the shortfall was seen most recently in Lebanon over the summer, when a UN peacekeeping force was brushed aside by warring parties -- and the UN Security Council was too divided to take swift, effective action on a ceasefire. That led many Arab countries to complain that the UN's credibility had been shattered.

UN limitations are being witnessed again right now in the Darfur region of western Sudan, where UN intervention to halt alleged genocide has effectively been blocked.

And UN weakness may be on embarrassing display again soon if no agreement is reached on the scale and range of sanctions against Iran over its suspect nuclear activities.

The UN, as the primary guardian of international peace and security, has also largely become a bystander concerning the two seminal conflicts of the recent past -- the US-led intervention in Afghanistan in 2001 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Although its humanitarian and development agencies are now playing a full role in Afghanistan, the UN has little or no say over what happens in Iraq. It was bypassed by the US and Britain, which decided to go to war without its mandate. Soon after, its Baghdad headquarters were bombed and its senior envoy in Iraq, Sergio Vieira de Mello, was killed.

The UN's impotence was long excused by the conditions created by the Cold War, which effectively froze the international order into spheres of influence. After the Cold War ended, the new excuse was that a rapidly changing geostrategic balance meant the rules had changed. That confusion contributed to the failures in Bosnia and Rwanda.

Post-Sept. 11, 2001, the UN's weakness is blamed on the ill-suitedness of its institutions to deal with new multi-dimensional threats and challenges, be they international terrorism or climate change.

But in reality, the basic problem facing the UN has not altered since its inception in 1945. It is hardly a problem that can be solved overnight. And the arrival of the well-intentioned but uninspiring Ban is not likely to make much difference to it.

The problem is the dominance of the Security Council by the five permanent members -- the US, Britain, Russia, China and France -- which also happen to be the five leading nuclear weapons states (although Israel may have unofficially usurped some of them in the atomic pecking order).

The power afforded by the UN rulebooks to these five countries alone, out of a total 192 members of the General Assembly, means that the UN, which can never ultimately be more than the sum of its parts, is effectively held hostage by the so-called "great powers."

They find it convenient to use the Security Council as a protective shield, diplomatic tool and excuse to promote inaction when inaction most suits their interest.

Alternatively, their pre-eminence allows them to ignore or stymie the UN when they are set on having their own way. Everybody on the council knows the way the game works. And the fact that each of the five exercises veto power means that uncomfortable confrontations, such as that before the Iraq war, are rare.

Annan did his best to respond to the new 21st century challenges facing the UN by urging a set of reforms in his report last year, called "In Larger Freedom." They included a new commitment to the Millennium Development Goals and stronger weapons of mass destruction proliferation safeguards.

Annan also advocated a collective "responsibility to protect" civilians from the more egregious actions of their governments.

Some of Annan's reforms, such as a new human rights council and peace building commission, have been adopted. And administrative investigations have cleaned out some of the poison pumped into the system by the Iraq-related "oil-for-food" scandal.

UN Deputy Secretary-General Mark Brown said this month that a good start had been made in building "three pillars" around which the UN would reorganize -- development, security and human rights.

But the key institutional reform -- enlargement of the Security Council to better reflect the interests and priorities of the whole international community -- has proved unobtainable.

Why so? Because the vested interests of the five permanent members in maintaining the status quo that suits them so well is too powerful.

Until this cartel is broken up, expect more tragic fiascos like North Korea, Lebanon and Sudan. And expect growing, righteous and increasingly violent rage in the developing world against the virtual monopoly of power enjoyed by the new and old empires of east and west.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its