"A salaryman can never have high hopes," Takao Kimijima says on a Tokyo street as he finishes a puff on his cigarette outside his non-smoking building.

The soft-spoken 30-year-old is not among the needy but a dark-suited corporate researcher who earns ? million (US$45,000) a year, slightly above average for full-time Japanese salaried workers.

But Kimijima is a closet sympathizer for Japan's new breed of slackers: young people who feel at ease picking and choosing their lifestyles, a no-no for their workaholic fathers who were derided abroad as corporate animals.

Kimijima says he has "no intention to work at the expense of my private life."

"I don't know if it was good or bad but Japan used to have lifetime employment and a seniority-based pay system on the assumption that its economy would keep expanding," he says.

"We are no longer living in such an era. Only a limited number of people are able to reap fruit while a vast majority can't expect their income to rise or even be stable," Kimijima says.

Nearby, a 34-year-old motorcyclist for a transport courier service sits on the ground in front of a convenience store drinking bottled tea.

"It's all up to you [whether to work hard]," he says. "I'm fine as I am, since I earn enough to make a living," he adds, declining to divulge his salary.

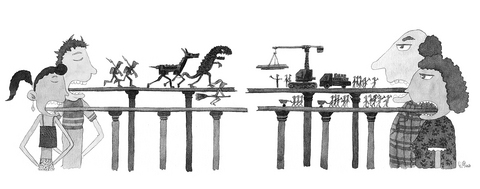

It is a long way from the time Japan was rebuilding from the ashes of war into an economic superpower, when the national motto was for everyone to work their hardest and earn in equal measure -- summed up as "100 million, all middle class."

The emergence of people who do not care about keeping up with the middle class was described in a best-selling book by marketing expert Atsushi Miura entitled Karyu Shakai, or "Low Society."

In the 1960s, television sets were symbols of middle-class living, but now "low society" people own -- and often indulge in -- gadgets such as DVD players and personal computers, Miura says in the book published last September.

"The low society is not absolutely poor in terms of material possession. So what is lacking in them? It is their will," he says.

They are not eager to communicate with others, work, learn or spend money on luxury goods.

"In short, they have low motivation for life," he says.

"You try to climb a mountain because you expect there must be something wonderful at its peak. It is natural that nobody bothers to climb to the top ... if you are already 70 percent high up and find plenty of things there," he says.

Many in the new "low society" are men in their early 30s who grew up after Japan accomplished its post-war miracle. They have not seen poverty or feared slipping from the middle class.

They prefer to "be myself," instead of the group identity which is deeply rooted in East Asia, Miura says.

The low society is a major factor in Japan's trend of marrying late and having fewer children, which has led to a decline in the population that has frightened economic policy makers.

Miura thinks that "slackers" also have cause for worry -- because their lifestyle is self-defeating.

"If the whole society is on an uptrend, you will be carried higher automatically. When the society stops rising, however, only the people who are willing to go higher will rise while others will go down," he says.

The Japanese economy as a whole has snapped out of its lost decade which followed the crash in the early 1990s of the speculative "bubble" boom.

But there are already signs of the rich becoming richer and the poor becoming poorer, which some critics blame on Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's rush to privatize, cut social services and reform the economy.

The number of Japanese households with no savings at all hit a record 23.8 percent last year, way up from 7.9 percent in 1995, even though household assets rose steadily, according to a survey by a research council affiliated with the Bank of Japan.

A survey by the Nihon Keizai Shimbun earlier this year found that 54 percent of Japanese believe they belong to the middle-class, down from 75 percent in 1987 when Japan was in the bubble.

In contrast, the ratio of people who believe they are in the lower class rose to 37 percent from 20 percent, the leading business daily said.

"What is unique to Japan is those people called `low society' are quite satisfied with their lives," says Ryuichiro Matsubara, an economics professor at the University of Tokyo.

"This is a very rare phenomenon among advanced countries. Here in Japan you don't see riots like those seen recently in France," where street protests forced the government to drop plans to ease job protection in hopes of reducing national unemployment.

"I think this is because Japan has developed a very peculiar consumption society since the late 1970s," he says, noting a wide variety of goods are sold at low prices thanks to cheap labor in China and other developing nations.

"You can enjoy life with freedom of choices guaranteed. Japan has established a social infrastructure that allows you to live a somewhat decent life unless you marry [and support a family]," he says.

Psychiatrist Hideki Wada says, "They don't take the matter seriously, believing they would not be homeless in today's Japan. On the other hand, they just have given up on going higher."

The lifestyle raises the eyebrows of older generations.

"You should strive to go higher as long as your life goes on," says Kenji Takizawa, a 52-year-old salesman for a food company.

"I'm also a father of two college students and want to earn even a single yen more," he says.

Still, he admits that the slacker life offers a certain appeal.

"I envy such people in a sense but I believe you shouldn't shun the fun and duty [of having a family]," he says.

Most Hong Kongers ignored the elections for its Legislative Council (LegCo) in 2021 and did so once again on Sunday. Unlike in 2021, moderate democrats who pledged their allegiance to Beijing were absent from the ballots this year. The electoral system overhaul is apparent revenge by Beijing for the democracy movement. On Sunday, the Hong Kong “patriots-only” election of the LegCo had a record-low turnout in the five geographical constituencies, with only 1.3 million people casting their ballots on the only seats that most Hong Kongers are eligible to vote for. Blank and invalid votes were up 50 percent from the previous

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

Beijing’s diplomatic tightening with Jakarta is not an isolated episode; it is a piece of a long-term strategy that realigns the prices of choices across the Indo-Pacific. The principle is simple. There is no need to impose an alliance if one can make a given trajectory convenient and the alternative costly. By tying Indonesia’s modernization to capital, technology and logistics corridors, and by obtaining in public the reaffirmation of the “one China” principle, Beijing builds a constraint that can be activated tomorrow on sensitive issues. The most sensitive is Taiwan. If we look at systemic constraints, the question is not whether