Meet little Lawrence. He's cute, he's clever, he's cherished ... and for every week of his little life, he's costing his parents another US$1,110.

There's nothing unusual about two-year-old Lawrence. He's just like thousands of other middle-class babies born in Hong Kong. The only difference is that, shortly before he was born, his parents sat down and worked out precisely how much he would cost them.

What they discovered goes a long way to explaining why the city has the lowest birth rate in the developed world. By the time Lawrence is 26, parents Janice and Louis expect to be US$1.5 million worse off than if they had never had him.

His kindergarten fees alone will set Janice and Louis back US$32,500, primary and secondary schooling US$232,200 and going to an overseas university and graduate school another US$413,000.

Then there are Lawrence's living costs -- US$122,500 for food, US$241,500 on clothes, US$56,500 on transport, US$93,000 on pocket money, US$22,700 on spectacles and eyecare, US$13,000 on visits to the dentist and US$107,000 on language and music lessons.

Janice, 38, managing director of an advertising agency, admits that if she and her financier husband had done their sums earlier, they may have thought twice about starting a family.

"It was a big dose of reality," she admitted.

"Our reaction was, `We shouldn't have worked that out,' because now we have got a lot of thinking to do about whether we [should] have a second. Cost is a key factor and it has a big influence on the number of children people have in Hong Kong these days. Our parents' generation didn't even think about it. They just went out and had babies and got on with life," she said.

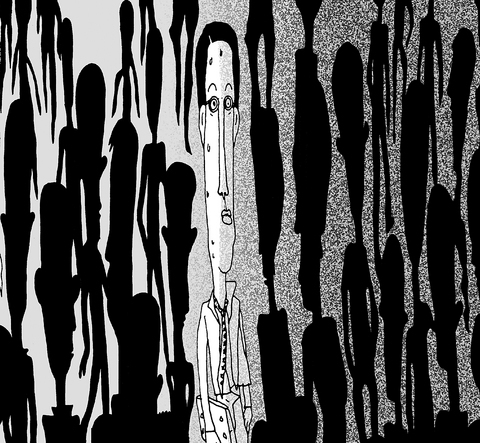

In today's Hong Kong, however, babies have become a luxury of choice and an indulgence that fewer and fewer young couples in the wealthy city of 6.8 million are opting to spend their hard-earned salaries upon.

In an increasingly competitive society, the cost of rearing a child to have the best possible chance of success is higher than ever. As a result, most couples now choose to remain childless or to stop at one child, and Hong Kong's birthrate has fallen from nearly three children per woman in 1980 to 0.9 last year.

It is a dilemma which has left Hong Kong facing a population crisis, with the number of elderly people aged over 64 expected to triple proportionately and account for nearly half the population by 2033.

There are cheaper choices, of course -- state schools, economies on clothes and less out-of-school activities. Louis and Janice looked into the potential savings and concluded that the most economical child-rearing in Hong Kong would leave them with a large bill of US$335,000 over 26 years.

Susan Lo, senior doctor with the Hong Kong Family Planning Association and mother of an eight-year-old daughter, said there had been a fundamental generational shift in family thinking.

"In the old days, people like my parents would think, `I will have children to safeguard my retirement. They will support me financially and psychologically and care for me in my old age,'" Lo said.

"If you ask the younger generation today, they will tell you it is nonsense to think of supporting your parents. They believe everybody should be responsible for their own lives," she said.

Lo conducted studies on Hong Kong couples considering having children and couples who have had one or two children and found that financial concerns were high on the anxiety list for both groups.

The most dramatic aspect of Hong Kong's falling birth rate is its sheer scale. No country in the world has seen such a steep decline over the past two decades, according to the think tank Civic Exchange.

While countries like the UK and Germany fret over what to do about their birth rates of 1.6 and 1.3 children per woman respectively, Hong Kong's fell to 0.8 percent in 2004 and rebounded to 0.9 last year.

Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang (曾蔭權) last year urged couples to have three children each. The government is meanwhile working on its first official population policy, which is expected to include incentives such as tax relief for bigger families.

A key factor driving birth rates down, Lo said, is the length of time children remain dependent on their parents.

"In the old days, when a child was 15 or 16, they could go out to work. Today, if my daughter is independent after getting her bachelor's degree, I would be very happy. People can expect to support their children up to when they finish their degrees when they are already in their 20s," she said.

Finances aside, Lo believes that Hong Kong's main problem is that in the maelstrom of modern urban living, people may have lost sight of what is important in life.

"In Hong Kong we seem to have gone to the extreme without looking back at the value of families," she said "We neglected to look at the reasons why a family is important -- bonding, cohesion, taking care of family members."

There may be a turn in the tide, however, Lo said.

"When SARS hit Hong Kong in 2003, people came to realize that spending time with the family is actually very pleasurable. Now that the economy is improving, there are signs too that attitudes may be changing," she said.

"A lot of people seem to be getting pregnant this year. I have had three friends who have had babies this month alone. People seem to be revaluating families again and starting to think more about family relationships rather than just `money, money, money,'" Lo said.

Surprisingly, despite realizing the financial impact baby Lawrence has had on their lives, Janice and Louis have decided they want a second child.

"We live in a competitive world and a sometimes very brutal world," Janice said. "When things happen, we only have our family to fall back on, and I want to give our son a family foundation. Having a brother or sister is something that has more value than money."

Lo, on the other hand, said: "I won't be having any more children. The main reason is because my daughter says she doesn't want siblings. I have been asking her since she was three-years-old and her reply has been `Definitely not.' I feel it is something I should honor if she still feels she is content to be an only child. She is happy because she has all the goodies, she has her own room -- and she has her parents to play with."

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its