Do you want to know which video clip will soon be scaring the daylights out of policymakers throughout the world? In a scenario that looks uncannily like the spread of a global pandemic, the economist Thomas Holmes has prepared a dynamic map simulation showing the spread of Wal-Mart stores throughout the US. Starting at the epicenter in Bentonville, Arkansas, where Sam Walton opened his first store in 1962, giant boxy Wal-Mart stores have now multiplied to the point where the average American lives less than 7km from an outlet.

Interestingly, the video shows how the stores spread out like petals of a flower, ever thickening and expanding. Rather than jumping out to the coasts -- 80 percent of all Americans live within 80km of the Pacific or Atlantic oceans -- Wal-Marts have spread organically through an ever-expanding supply chain. Even though each new store takes away business from Wal-Mart stores established nearby, ever-improving supply efficiencies help maintain the chain's overall growth.

Love them or hate them, what is undeniable is that Wal-Mart is the quintessential example of the costs and benefits of modern globalization. Consumers pay significantly less than at traditional outlets. For example, economists estimate that the food section of Wal-Mart charges 25 percent less than a typical large supermarket chain. The differences in price for many other consumer goods is even larger.

Consider the following stunning fact: Together with a few sister "big-box" stores (Target, Best Buy and Home Depot), Wal-Mart accounts for roughly 50 percent of the US' much vaunted productivity growth edge over Europe during the last decade. Fifty percent! Similar advances in wholesaling supply chains account for another 25 percent. The notion that the US has gotten better at everything while other rich countries have stood still is thus wildly misleading. The US productivity miracle and the emergence of Wal-Mart-style retailing are virtually synonymous.

I have nothing against big-box stores. They are an enormous boon to low-income consumers, partly compensating for the tepid wage growth that many of them have suffered during the past two decades. And I don't agree with friends of mine who turn their noses down at Wal-Mart stores, and claim never to have visited one. As a consumer, I think big-box stores are great. They have certainly been great for America's trading partners; Wal-Mart alone accounts for over 10 percent of all US imports from China.

But I do have some reservations about the Wal-Mart model as a blueprint for global growth. First, there is the matter of its effect on low-wage workers and smaller-scale retailers. While completely legal, studies suggest that Wal-Mart's labor policies exploit regulatory loopholes that, for example, allow it to sidestep the burden of healthcare costs for many workers (Wal-Mart provides healthcare coverage to less than half its workers). And the entry of big-box stores into a community crushes long-established retailers, often traumatically transforming their character.

Yes, to some extent, such is the price of progress. But the loss of aesthetics and community is not easily captured in simple income and price statistics. Big-box stores are not exactly attractive -- hence their name. If they continue their explosive growth over the next 20 years, will Americans someday come to regard their proliferation as a spectacular example of the failure to adopt region-wide blueprints for balanced growth?

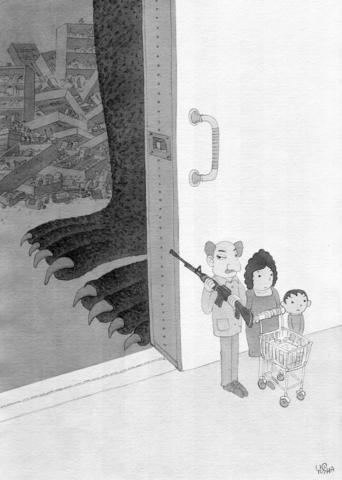

Indeed, many Europeans, and others, will view Holmes' video simulation of Wal-Mart's spread as a horror film. The French may have invented the hypermart -- the forerunner of the big-box store -- but they never intended to let their growth go unchecked. The big question for Europeans is whether they can find ways to exploit some of the efficiency gains embodied by the Wal-Mart model without being overrun by it.

For the US, there is the additional question of what to do when the big-box store phenomenon has run its course. If so much of the US productivity edge really amounts to letting Wal-Mart and its big-box cousins run amok, what will happen after this source of growth tapers off? The US economy has many other strengths, including its superior financial system and leading position in high-tech capital goods, but the fact remains that the US' advantage in these areas has so far not been nearly as striking as the Wal-Mart phenomenon. It is curious how many people seem to think that the US will grow faster than Europe and Japan over the next 10 years simply because it has done so for the past 10 years.

Wal-Mart and its ilk are a central feature of the modern era of globalization. They are not quite the pandemic that their explosive growth pattern resembles, but nor is their emergence completely benign. Those who would aim to emulate US productivity trends must come to grips with how they feel about big-box stores sprouting across their countryside, driving down wages and plowing under smaller-scale retailers. The US, in turn, must think about where the proper balance lies between aesthetics, community and low prices.

Kenneth Rogoff is professor of economics and public policy at Harvard University, and was formerly chief economist at the IMF.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its