Two billion people are watching by live telecast, and American Miss World hopeful Nancy Randall is about to address the world in Chinese, a language notorious for its embarrassing pitfalls.

"I love you, Sanya!" she says in Mandarin to the camera. "I love you, China!"

The all-smiling anthropology graduate from Louisiana pulls it off. Around the auditorium, grey-suited party cadres break into applause, and the home crowd ripples with delight. If this is diplomacy, it's honey-coated -- and when next Saturday the Chinese resort of Sanya once again plays host to this year's Miss World final, all involved will be hoping for plenty more of the same.

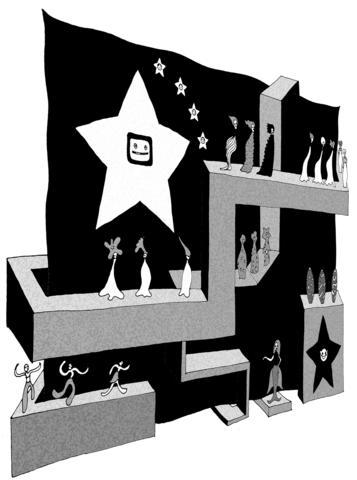

Miss World is the largest live annual TV event on Earth, and this year's contest will be the biggest in its 55-year history. And with memories still fresh of the mass rioting in Nigeria in 2002, when the contest was forced at the last minute to move to London, Miss World may just have found a home in Sanya, the principal resort on Hainan -- the subtropical island tourist chiefs like to call "China's Hawaii," and to which the contest is returning for the third successive year.

The country's feminist groups may grumble, but there is little doubt that overall the Chinese are very happy hosts. The 115 contestants have been in China for weeks. The first stop on an ambitious month-long tour was the east-coast city of Wenzhou, an economic pace-setter but not a spot that tends to figure on tourist itineraries. With state media in hot pursuit, the girls visited a market, toured the local beauty spots and served as bridesmaids in a surreal televised mass wedding.

The city's senior official, Mayor Xu, even stepped up to help judge the first of this year's fast-track qualifying rounds, the talent show.

This represents a massive change in attitude, says Wang Zheng, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, who grew up in Shanghai.

"After the famine of the early 1960s, the official media began to promote a more frugal lifestyle," she says. "Simplicity was seen as a virtue of the proletariat, and there was an emphasis on `proletarian style' -- army uniforms or peasants' and workers' outfits. Everything else was condemned as bourgeois."

Wang Zheng recalls the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

"Groups of Red Guard students took to the streets to police women's clothing and hairstyles," she remembers. "If they didn't like what a woman wore, they would cut up her clothes or shoes in public."

Wang's elder sister was one such victim -- a young teacher with naturally wavy hair. Her own pupils accused her of wearing a Western-style perm, she was publicly criticized, and forced to hand over one of her favorite garments, a jean jacket with a sailor collar.

Chances are, the Red Guards won't be much in evidence at the Sanya Sheraton next Saturday.

"People here are very enthusiastic about Miss World, and beauty contests in general," says Steven Crane, managing editor of Lifestyle magazine

That's Shanghai.

"Most of these events sell out -- and they receive wide coverage in the official Chinese media."

While British coverage will be provided by the relatively obscure satellite channel Sky Travel, in China the event will go out live on state broadcaster CCTV, clearly with the support of party bosses.

What's in it for them? Tourist dollars, for a start. Hainan may always have had the climate, but the island was once a corrupt, denuded outpost, far from the spoils of government in Beijing. It was a place of exile inhabited by wild aboriginal tribes such as the Li, whose women disfigured their faces with tattoos, supposedly to make themselves unattractive to their plundering neighbors. These days, Li women perform for tourists in the swanky international developments of Sanya town.

For a regime keen to publicize its economic success and internationalist credentials at home and abroad, the month-long beauty-fest is propaganda gold dust. Miss World may not yet have her own float in the National Day parade in Tiananmen Square; but in a country where media content still falls under governmental control, the heavy coverage that the contest receives sends a powerful signal that the senior cadres feel the contest serves their ends.

Domestic TV coverage has a clearly defined political function. In general, the Chinese media like to broadcast footage of resident Westerners going about their daily lives. Inevitably the subject is shown praising China -- and if, like last year's Miss USA Nancy Randall, they do so in endearingly elementary Chinese, all the better. This kind of material has a significance over and above the feel-good factor; it underlines the success of recent liberalizing policies.

Meanwhile on an international level the Miss World contest allows a carefully constructed Chinese message to be broadcast to an audience of 2 billion across the globe. Over the past 10 years the Chinese have worked hard to dispel once ubiquitous images of China, the bicycling factory state, and glamorous events like Miss World are a tonic. Not only that -- the contest sends a strong message to the world about China's changing values and internationalization, that the days of the Red Guards are over.

"This sort of programming helps build an international image that is unthreatening and somehow reassuring," Crane says. "After all, beauty pageants were once considered as American as apple pie."

China, it seems, is getting its money's worth from the relationship -- and Miss World hardly has cause to complain.

"The Miss World Organization receives two things: an exotic locale, and a public that doesn't yet view such contests as passe or sexist," Crane says.

But does no one in China think this is all just a little odd? Organizations like the All-China Women's Federation, the largest women's organization in China, have raised dissenting voices. Wang Zheng would like to hear a real debate.

"Miss World tells Chinese women that their appearance defines who they are. It tells them a woman's value hinges on the way she looks," Wang says.

But, at a time when state mouthpiece China Daily reports the establishment of the "Chinese beauty standard" ("a Chinese beauty must have ... a distance of 35mm between the eyes"), all the money points in the opposite direction. It's like a church leader denouncing the excesses of TV show I'm a Celebrity; in other words, the old guard may get their platform -- but in the end many young Chinese women seem more inclined to buy into the burgeoning world of beauty products and cosmetic surgery than listen to the old-sounding arguments of a once revolutionary generation.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its