The advent of nanotechnology, the branch of engineering that seeks to build objects molecule by molecule -- indeed, atom by atom -- has evoked futuristic images of self-replicating "nanobots" that perform surgery, or that convert the planet into a mass of "grey goo" as they consume everything in sight.

These two scenarios follow a familiar story line: technological progress, such as the development of nuclear power, genetically modified organisms, information technologies and synthetic organic chemistry, first promises salvation, but then threatens doom as the consequences, often environmental, become apparent. Even disinfecting water -- the single most important technological advance ever in prolonging human life -- turns out to produce carcinogenic byproducts. The cycle of fundamental discovery, technological development, revelation of undesirable consequences, and public aversion appears unbreakable.

Will nanotechnology be different? Along with the early euphoria and hype that typically surround the rollout of new technologies, nanotechnology has been the subject of projections concerning its possible environmental risks well before its wide-scale commercialization. Raising such questions when nanotechnology is still in its infancy may result in better, safer products and less long-term liability for industry.

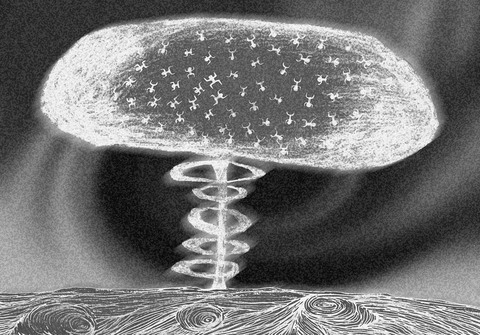

ILLUSTRATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

The rapidly developing nanomaterials industry is the nanotechnology that is most likely to affect our lives first. A 2003 estimate by the Nanobusiness Alliance identified nanomaterials as the largest single category of nanotech start-ups.

In the environmental technology industry alone, nanomaterials will enable new means of reducing the production of wastes, using resources more sparingly, cleaning up industrial contamination, providing potable water, and improving the efficiency of energy production and use.

Commercial applications of nanomaterials currently or soon to be available include nano-engineered titania particles for sunscreens and paints, carbon nanotube composites in tires, silica nanoparticles as solid lubricants, and protein-based nanomaterials in soaps, shampoos and detergents.

The production, use and disposal of nanomaterials will inevitably lead to their appearance in air, water, soils or organisms. Research is needed to ensure that nanomaterials, and the industry that produces them, evolve as environmental assets rather than liabilities.

Unfortunately, little is known about the potential environmental impacts of nanomaterials. Ironically, the properties of nanomaterials that may create concern, such as nanoparticle uptake by cells, are often precisely the properties desired for beneficial uses in medical applications.

For example, 10 years of studies of the possible health effects of a class of carbon-based nanomaterials known as fullerenes report that the soccer-ball-shaped fullerene molecules known as "buckyballs" are powerful anti-oxidants, comparable in strength to vitamin E. Other studies report that some types of buckyballs can be toxic to tumor cells.

Two recent studies concluded that buckyballs could impair brain functions in fish and were highly toxic to human-tissue cultures. But the conclusions from these studies are difficult to interpret, in part because the nanomaterials that they used were contaminated with an organic solvent added to mobilize the fullerenes in water.

A subsequent study of fullerene toxicity found no significant toxicity for buckyballs, but did observe a toxic response in cell cultures to a second group of fullerenes, called "single-wall nanotubes." At this point, the question of the possible toxicity of fullerene nanomaterials remains largely unanswered.

Determining whether a substance is "dangerous" involves determining not only the material's toxicity, but the degree to which it will ever come into contact with a living cell. Toxicity can be evaluated by putting buckyballs into a fish tank, but we must also find out whether buckyballs would ever actually arrive in a real world "fish tank"such as a lake or river.

We do know that when materials resist degradation, they may be present in the environment for long periods of time, and thus have a greater chance of interacting with the living environment. But processes that may lead to the breakdown of nanomaterials, including degradation by bacteria, are virtually unexplored.

Moreover, like toxicity and persistence, little is known about how nanoparticles are likely to move about in the environment. The most dangerous nanomaterials would be those that are both mobile and toxic. The fullerenes that have been the focus of early toxicity studies are among the least mobile of the nanomaterials we have studied to date.

Our initial work on nanomaterial mobility in formations resembling groundwater aquifers or sand filters has shown that while one type of nanomaterial may be very mobile, a second may stay put. Thus, each nanomaterial may behave differently.

Concerns over nanomaterials' possible effects on health and the environment have perhaps overshadowed the pressing need to ensure that their production is clean and environmentally benign. Indeed, many of the ingredients used to make nanomaterials are currently known to present risks to human health.

An encouraging trend is that the methods used to produce nanomaterials often become "greener" as they move from the laboratory to industrial production. Setting aside the issue of nanomaterials' toxicity, preliminary results suggest that fabricating nanomaterials entails risks that are less than or comparable to those associated with many current industrial activities.

It would be naive to imagine that nanotechnology will evolve without risks to our health and environment. While attempting to halt the development of nanomaterial-inspired technologies would be as irresponsible as it is unrealistic, responsible development of these technologies demands vigilance and social commitment.

Environmentally safe nanotechnology will come at a cost in time, money and political capital. But with foresight and care, nanotechnology can develop in a manner that will improve our wellbeing and that of our planet.

Mark Wiesner is director of the Environmental and Energy Systems Institute at Rice University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its